South Africa should consider concentrated solar power (CSP) with storage for base load energy since it has the capacity to replace Eskom’s ageing coal-fired power stations.

This is the message of Nandu Bhula, CEO of the Bokpoort CSP plant near Groblershoop in the Northern Cape. Bhula believes the performance of this plant proves his argument.

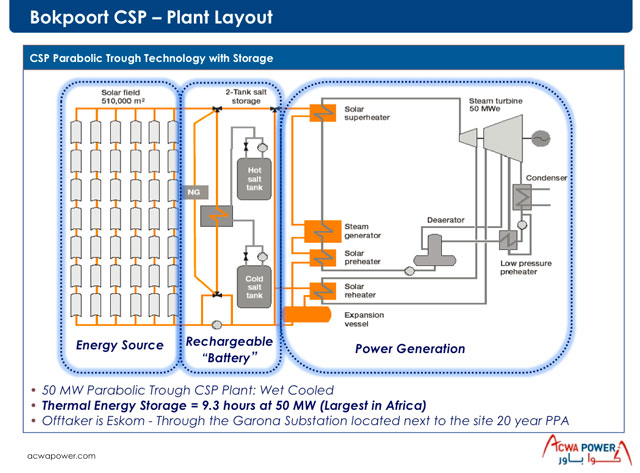

Bokpoort, with a nameplate electricity generation capacity of 50MW, has the capacity to store enough energy for 9,3 hours of electricity generation at the level of 50MW, once the sun sets.

If it reduces the output to 30MW as the electricity demand drops after the evening peak, it can run 24 hours per day.

This was illustrated when Bokpoort ran nonstop for 14 consecutive days, ended 31 March, at an average load factor of 66%. (Load factor measures efficiency and is the ratio of actual electricity output divided by maximum potential output.)

The assumption in South Africa’s Integrated Resource Plan (IRP) is that the typical load factor for a CSP plant with nine hours of storage capacity would be 43%, but Bhula believes it should be at least 60%.

According to Eskom spokesman Khulu Phasiwe, the load factor of Eskom’s coal-fired power station is between 78% and 90% and for the Koeberg nuclear power plant it is 90%. In its previous annual report, Eskom said the average load factor for all renewables connected to the grid was almost 31%. That includes various technologies.

Bhula says it is essential to have the IRP reviewed if South Africa wants to utilise CSP to its full potential.

In the IRP it is further assumed that the lead time to completion of a CSP plant with nine hours of storage is four years. The Bokpoort experience shows that an average load factor of 60% and lead time of three years is realistic, Bhula says.

The R5bn Bokpoort plant that started commercial operations on 19 March, consists of eight solar fields with 241 920 mirrors with a combined reflective surface of 658 000sq m. The mirrors follow the sun like sunflowers and concentrate the solar energy on tubes filled with oil.

The oil is heated to 400 deg C and transported to heat exchangers where it is either used to generate steam for generating electricity for direct output or to bank the heat in a huge salt tank to be used later when the sun is no longer available, to generate electricity.

It takes about 30 minutes to switch from direct output to generation from stored energy, Bhula says.

Based on the outdated IRP assumptions, CSP is regarded as a peaking technology and tariffs are set accordingly. That means that CSP tariffs provide for a base tariff during the day, that is multiplied by 2,7 times during peak and a zero tariff from 10pm to 6am, Bhula says. The tariff therefore incentivises the reduction, rather than the increase of storage capacity, he says.

The effect of the tariff signal is clear from the fact that Bokpoort in the second round of the department of energy’s renewable energy procurement programme was designed with 9,5 hours of storage, Redstone in round three with 12 hours storage and CSP1 in round for with a reduced 7,5 hours of storage, Bhula says.

“Why would you provide it (storage capacity) if it cannot earn you money?” he asks.

Bhula says Eskom will have to start decommissioning its older power stations by 2020. If South Africa changes its approach to CSP and expands the CSP allocation, CSP with proper storage could replace these decommissioned stations, he says.

He says as a technology, CSP plants are probably less prone to sudden load losses than coal-fired plants. The only reason for load losses is the weather and that could in most cases be fairly well predicted from the viewpoint of the system operator.

The country has some of the best solar resources in the world and more than enough space to build enough CSP plants. A big CSP drive could provide the necessary economies of scale to develop a proper local supply chain and the location of the plants in rural South Africa could go a long way to reverse the deterioration of rural economies, Bhula says.

In the tiny town of Groblershoop with a population of about 9 000 for example, Bokpoort has created 1 300 jobs at the peak of construction and 62 permanent jobs during operations. This makes a huge difference in the small rural economy.

The huge high temperature fluid overflow and expansion vessels for the plant were built in Johannesburg and the metal components for the two salt tanks, both 14m high with a diameter of 40m, were constructed and assembled on site by a firm from nearby Upington.

Bokpoort further supplied 305 homes in Groblershoop with solar energy for running their lights, television and radio to the value of R1,2m and installed a water reticulation plant and connected 77 houses in nearby Topline village with running water for the first time.

Bhula said the tariffs agreed upon for CSP has dropped from about R3/kWh from the first bid round to R1,20/kWh in the fourth round, which makes it competitive with Eskom’s new coal power stations. He believes CSP tariffs could drop further if an expanded programme could provide further economies of scale.

Bokpoort is a ring-fenced company with the Saudi power developer ACWA Power (40%) as controlling shareholder. The other stakeholders are Lereko Metier through different vehicles (25%), the Public Investment Corp (25%) and a community and BEE trust with a combined 5%.

- This article was originally published on Moneyweb and is used here with permission