An unemployment rate of 29%, an economy stuck in the longest downward cycle since World War 2, chronic electricity shortages and soft business confidence — after 20 months running South Africa, patience is wearing thin with Cyril Ramaphosa’s languid pace of reforms.

There have been no shortages of policy papers, conferences and speeches outlining how to unlock economic growth, but the deeply divided ANC and its labour union and communist allies have struggled to agree on a way forward. Bailouts for Eskom are draining the state’s coffers and plans announced months ago to split it into three operating units and reorganise its R440-billion mountain of debt remain a work in progress.

“We are desperate for some real action on Eskom,” Neal Froneman, the CEO of Sibanye Gold, the country’s biggest private employer, said in a 25 October interview with Bloomberg. “You have to make some tough decisions. It just blows my mind that we don’t just get on and do it.”

The disenchantment is evident in the financial markets, with the rand down 20% against the dollar since Ramaphosa took office. The nation’s bond yields are the highest of any country with an investment-grade credit rating.

Ramaphosa said in a speech in London this month that plans to deal with Eskom’s debt will be announced soon and he’d found ways to stabilise the state’s finances that will appease Moody’s Investors Service — the only major rating company that doesn’t classify the nation’s debt as junk.

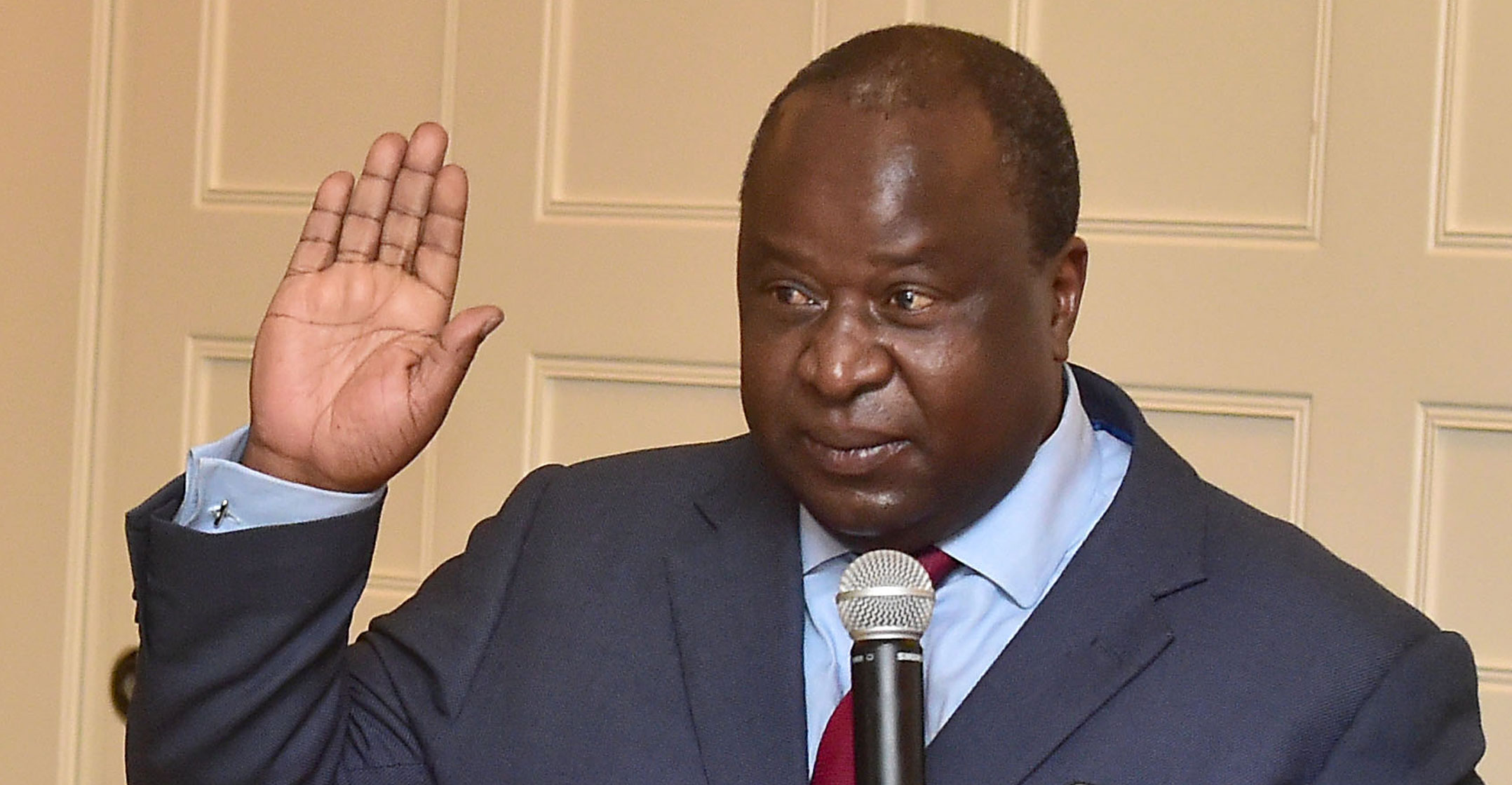

Focus now shifts to finance minister Tito Mboweni, who may give more clarity when he unveils his mid-term budget on 30 October.

The president has also pledged to cut red tape to promote investment and commerce and is targeting a top-50 position in the World Bank’s rankings for ease of doing business within three years. South Africa slipped two places to 84th in the institution’s latest list published on 24 October.

Difficult

Part of Ramaphosa’s problem is that implementing reforms is difficult at the best of times, and these aren’t the best of times.

The president’s hold on the ANC is tenuous and his administration lacks technical experience, said Ivor Sarakinsky, a lecturer at the University of Witwatersrand’s School of Governance in Johannesburg.

“It’s very hard to turn complex organisations around and consensus is probably the best way in order to ensure sustainable results,” Sarakinsky said by phone. “If he goes into these processes and uses the authority he has, he can alienate people who are sitting on the fence and push them over to the other camp.”

Besides the lack of clarity on plans to fix Eskom, investors remain in the dark about how a contentious ANC decision to change the constitution to make it easier to seize land without compensation will be implemented.

Also, proposals made by national treasury in August that the state relinquish its near-monopoly of electricity, port and rail services and privatise assets were met with a lukewarm response from the ruling party.

“There is disenchantment with the pace of change,” Mcebisi Jonas, a former deputy finance minister and incoming chairman of telecommunications company MTN Group, said in a 24 October speech. “We need a few measures of shock therapy to get the economy growing. It’s not delivering more speeches, it’s about doing.”

Finance minister Mboweni notes that even when the government and ANC do take decisions, it doesn’t follow through on them because the state lacks capacity.

“If at least we implement about 30% of the things which we say we’re going to implement, we’ll be making great progress,” he said in a speech in Pretoria on 17 October. “We have a problem in that the key economic actors are not moving in the same direction, they’re pulling away from each other.” — Reported by Amogelang Mbatha and Mike Cohen, with assistance from Antony Sguazzin, Prinesha Naidoo and Felix Njini, (c) 2019 Bloomberg LP