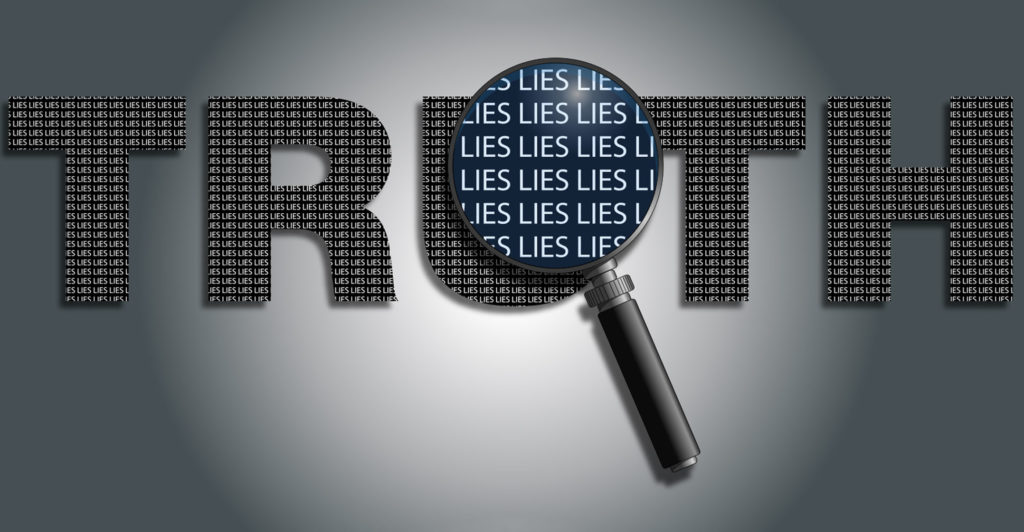

Propagandist cyber tactics planted during the Zupta era must be uprooted so that South Africans can assert that factual accuracy and truth matter.

Over the past few years, the battle over what constitutes the truth has intensified throughout the world. There has even been talk of a “post-truth world”. The comedian Stephen Colbert coined the word “truthiness” on his show in 2005. He saw “truthiness” as an appeal to emotion or “gut feeling” rather than evidence.

Colbert was referring to then-US President George W Bush’s decision to invade Iraq in 2003, claiming that Saddam Hussein had a stockpile of weapons of mass destruction. After the invasion, it was discovered that there were no WMDs in Iraq.

Russia’s cyberwar against Europe and the US has taken the attack on truth to new heights. To what extent is this also true for South Africa?

The historian, Timothy Snyder, in his book The Road to Unfreedom, identifies a Russian strategy in its information war as “implausible deniability”, which is best illustrated by President Vladimir Putin’s blunt denial that Russia invaded Ukraine in 2014. Putin said: “We have no intention of rattling the sabre and sending troops to Crimea.” But he had already sent troops to Crimea. Putin was not concerned about the facts. He had “surmised that lies unite rather than divide Russia’s political class. The greater and more obvious the lie, the more his subjects demonstrated their loyalty by accepting it.”

Russia’s second propaganda strategy was to proclaim its innocence: “The invasion was not a stronger country attacking a weaker neighbour at a moment of extreme vulnerability, but a righteous rebellion of an oppressed people against an overpowering global conspiracy.”

Russian soldiers did not wear any insignia on their uniforms that might have identified them. There were no markings on Russian weapons, equipment or vehicles. Snyder notes: “The point was to create the ambience of a television drama of heroic locals taking unusual measures against titanic American power (however improbable).

‘Narrative sense’

Russians would be expected to believe the preposterous: that the soldiers they saw on their television screens were not their own army but a ragtag band of can-do Ukrainian rebels defending the honour of their people against a Nazi regime supported by infinite American power. The absence of insignia was not meant as evidence, but as a cue about how Russian viewers were supposed to follow the plot. It was not meant to convince in a factual sense, but to guide in a narrative sense.”

These propaganda strategies were used in Russia’s cyberwar to support US President Donald Trump’s candidacy for president in the 2016 American election. Russia’s strategy was to destabilise American democracy and attack any attempt to establish the truth.

Snyder argues that Trump’s presidential bid took place in three phases, each of which relied on American susceptibility and cooperation.

First, Russians had to transform a failed real estate developer into a recipient of their capital, by buying his properties. Second, this failed real estate developer had to be portrayed on American television as a successful businessman. Finally, Russia supported the fictional character “Donald Trump, successful businessman” in the 2016 presidential election.

To support Trump, Russia unleashed a cyberwar. Snyder observes: “In a cyberwar, an attack surface is the set of points in a computer program that allow hackers access. If the target of a cyberwar is not a computer program but a society, then the attack surface is something broader: software that allows the attacker contact with the mind of the enemy. For Russia in 2015 and 2016, the American attack surface was the entirety of Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Google.”

If it is true that Russia has developed an advanced cyberwar capability over social media networks, then it is worth considering if this has relevance for South Africa.

In his visits to Russia or to Brics meetings over the past decade, did former President Jacob Zuma discuss Russia’s expertise in cyberwar and the propagandistic value of a TV news channel like RT? Did he solicit party-political funding for the ANC from Russian oligarchs? Who hatched the scheme for the Guptas to buy the Tegeta mining company with its uranium assets in anticipation of a Russian deal for the supply of nine nuclear reactors? Was Gupta-owned television news channel ANN7 modelled on RT, with an Indian twist?

What is known is that the Guptas hired the British PR firm, Bell Pottinger, to launch a disinformation campaign that would divert attention from the “state capture” narrative that was a threat to Zupta interests. This was evident in the attack on Thuli Madonsela’s State of Capture report; in civil society’s resistance to the nuclear deal; and in extensive litigation and use of parliamentary debates by the Democratic Alliance and the Economic Freedom Fighters against Zupta positions.

Bell Pottinger’s strategy was to introduce an enemy in the form of “white monopoly capital”, and to blame it for South Africa’s woes. The solution — borrowed from the EFF — was “radical economic transformation”.

Local proxies

Local proxies such as Black First Land First (BLF) were deployed to assail South Africans with these narrative positions on Twitter and through political advertising on Facebook.

BLF also staged attacks against journalists, countering their assertions of truth with untruths, staking out their homes, and disrupting “city hall”-style meetings of investigative journalism unit Amabhungane.

South Africans did not take this lying down. Bell Pottinger was attacked on social media and accused of fanning racial tensions. The DA complained to the British Public Relations and Communications Association (PRCA) about the ethics of Bell Pottinger’s campaign. The PRCA expelled Bell Pottinger and its business collapsed.

Were Russian cyberwar capabilities deployed on South African social media? Did Russia’s shadowy Internet Research Agency create fake accounts to promote political messages in support of the Guptas’ Bell Pottinger campaign, which would artificially generate millions of “likes”, thereby pushing “white monopoly capital” propaganda into the newsfeeds of South African social media users?

Did Russian agents place political advertisements on Facebook and promote them as memes across Instagram? Did Russian cyberwarriors exploit Twitter’s capacity to drive its messaging using bots?

After Bell Pottinger was eliminated from the battlefield, the “white monopoly capital/radical economic transformation” messaging continued and was in all likelihood integrated into the Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma campaign for the ANC presidency in December 2017.

Was there a Russian hand in this?

It appears that the NDZ campaign followed Putin’s strategy to alternate himself with Dmitry Medvedev, who switched between the roles of president and prime minister in order to retain power in the Kremlin.

If Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma had won the ANC presidency, it is likely that Jacob Zuma would still be South Africa’s president today.

Snyder has much to say about the failure of political succession in Russia as a marker of an authoritarian state. South Africa came close to this fate.

What else can be said about Zuma and the Russian connection? Did he get the idea for ANN7 from the Russian model of RT? A recent book, Indentured: Behind the Scenes at Gupta TV, by ANN7’s first executive editor, Rajesh Sundaram, reveals Zuma’s personal involvement in the establishment of the TV channel, in which his son, Duduzane, held a 30% stake.

At several meetings, Jacob Zuma offered his advice as to how ANN7 should position itself politically, by making positive news stories of ordinary people’s lives improving under his watch, which would counteract critical news stories. This is reminiscent of Hlaudi Motsoeneng’s efforts at the SABC to promote 70% good news stories on its news services.

These are questions for the State Capture Commission under the chairmanship of deputy chief justice Raymond Zondo to investigate.

Broad cyberattack surface

Was there a Russian hand in the propaganda campaigns initiated by Zuma and the Guptas on television, in the press and across social media? It is important for South Africans to know the extent to which their news sources were fed by propaganda across a broad cyberattack surface that undermined the basis of factuality — of truth.

It is likely that this media/cyberwar campaign is taking on a new form in the post-Zuma era. For example, with the debate on land and “expropriation without compensation” dominating the news, there has been an escalation of social media coverage of maps showing land ownership that excludes land owned by the Ngonyama Trust and other traditional leadership.

The framing of the land debate has the potential to fan racial tension in the nation rather than facilitating serious debate on how to effectively and ethically redistribute land.

It will be important for the Zondo commission to get to the truth of the propagandistic destabilisation of the country’s thought processes.

- Willie Currie is a former councillor of Icasa and Melody Emmett is a freelance writer and copy editor