“This machine kills fascists,” read the words on a guitar that American folk singer, Woody Guthrie, used to carry. In Quentin Tarantino’s World War 2 epic, Inglourious Basterds, the film camera has a rather more ambiguous relationship with the Nazis.

Like all Tarantino films, Inglourious Basterds is a movie about the cinema. Just as Reservoir Dogs was a homage to the heist films of the 1970s and Kill Bill Volume 1 was a love letter to Hong Kong kung-fu flicks, Basterds is Tarantino’s tribute to the great World War 2 adventures of the 1960s such as Kelly’s Heroes and The Dirty Dozen.

From the opening of the first chapter — titled “Once Upon a Time in Nazi-Occupied France” — and the snatches of Ennio Morricone music, it’s clear that this is as much a spaghetti Western as it is a war film.

As the film unfolds, it becomes apparent that Inglourious Basterds isn’t just a playful parade of cinematic references. It’s also a subtle questioning of the language of cinema, much of which is borrowed from unpalatable propaganda films and cut loose from its original context.

Inglourious Basterds tracks two stories which converge over its running time and culminate in fiery justice for cinema and history’s ultimate bad guys. The first of these is about a young Jewish girl, Shosanna Dreyfus, who escapes death at the hands of the urbane and cunning Nazi colonel Hans Landa.

Four years later, she’s running a cinema in Paris that has been chosen to host the première of a film masterminded by Nazi propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels. Apart from Goebbels, Hitler, Landa and other high-ranking Nazi brass will be in attendance.

The second narrative strand follows a small squad of soldiers — the Basterds of the title — as they try to capitalise on the opportunity to kill the top members of the Nazi party assembled to watch the film and thus end World War 2 once and for all.

The Basterds are a group of Jewish American soldiers parachuted behind enemy lines to sow terror among rank-and-file Nazi troops by killing as many of them as possible and as brutally as possible.

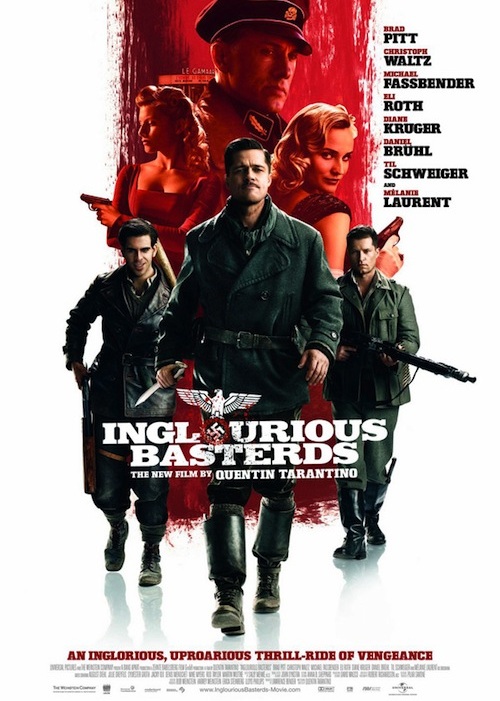

They’re led by lieutenant Aldo Raine, a half-Apache tracker, who demands 100 Nazi scalps from each of the men under his command. Brad Pitt, one of the few big Hollywood stars in the film, plays Raine with a larger-than-life Tennessee drawl and a mischievous twinkle in his eye.

Many other members of the cast are well known in Europe but may not be familiar to Hollywood audiences. Tarantino shows his usual eye for fantastic casting. Beautiful, young French actress Mélanie Laurent brings a steely edge to Shosanna while German actor, Christoph Waltz, is a chilling scene-stealer as Landa.

Like many Tarantino films, Inglourious Basterds is long, excessively talky and punctuated with moments of extreme violence. Here, the long running time doesn’t zip past as quickly as it did in Pulp Fiction, nor does the dialogue crackle with as much energy and wit. Many viewers will be exasperated by long stretches of dialogue about now-obscure French and German film-makers of the 1930s and 1940s.

It’s a hard movie to make sense of from just one viewing. I suspect many jokes and allusions will only reveal themselves with multiple viewings. Though far from the director’s most enjoyable film, it’s certainly one of his most ambitious.

Some have dismissed it as a simple revenge fantasy while others see it as an affirmation of cinema’s power as a machine to fight fascists. Many critics see it as a tasteless retelling of history that trivialises the real sufferings of World War 2.

Tarantino seems acutely aware that many common cinematic techniques were first used by fascist film-makers, often working in the service of evil men like Goebbels. There’s ambivalence to this revenge film that lifts it above most of the others it borrows from so liberally. — Lance Harris, TechCentral

- Inglourious Basterds opens in SA on 23 October

Subscribe to our free daily newsletter