It probably happens every minute of the day: a little girl demands to see the photo her parent has just taken of her. Today, thanks to smartphones and other digital cameras, we can see snapshots immediately, whether we want to or not. But in 1944 when 3-year-old Jennifer Land asked to see the family holiday photo that her dad had just taken, the technology didn’t exist. So her dad, Edwin Land, invented it.

Three years later, after plenty of scientific development, Land and his Polaroid company realised the miracle of nearly instant imaging. The film exposure and processing hardware are contained within the camera; there’s no muss or fuss for the photographer who just points and shoots and then watches the image materialize on the photo once it spools out of the camera.

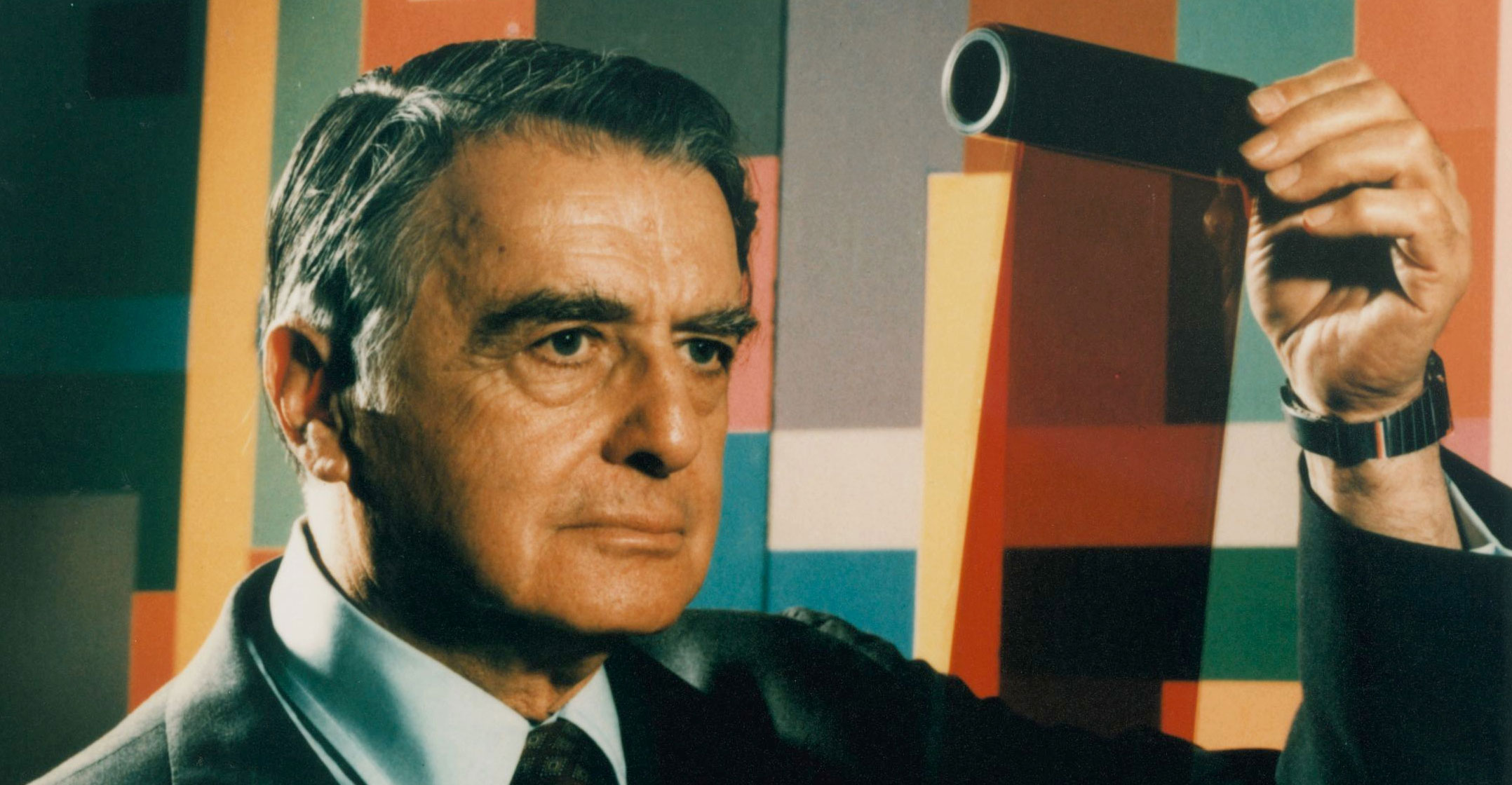

Land is probably best known for the “instant photo” — or the spiritual progenitor of today’s ubiquitous selfie. His Polaroid camera was first released commercially in 1948 at retail locations and prices aimed at the post-war middle class. But this is just one of a host of technological breakthroughs Land invented and commercialised, most of which centred on light and how it interacts with materials. The technology used to show a 3D movie and the goggles we wear in the cinema were made possible by Land and his colleagues. The camera aboard the U-2 spy plane, as featured in the movie Bridge of Spies, was a Land product, as were even some aspects of the plane’s mechanics. He also worked on theoretical problems, drawing on a deep understanding of both chemistry and physics.

I’m a vision scientist who has touched many of the fields in which Land made great advances, through my own work on new imaging methods, image processing techniques and human colour vision. As the 2018 recipient of the Edwin H. Land Medal, awarded by the Optical Society of America and the Society for Imaging Science and Technology, my own work relies on Land’s technological innovations that made modern imaging possible.

Edwin Land’s first optics breakthrough came as a young man, when he figured out a convenient and affordable method to control one of the fundamental properties of light: polarisation.

You can think of light as waves propagating from a source. Most light sources produce a mixture of waves with all different physical properties, such as wavelength and amplitude of vibration. Light is considered polarised if the amplitude varies in a consistent manner perpendicular to the direction the wave is travelling.

Given the right material for the light waves to pass through, they may be rotated into another plane, slowed down or blocked. Modern 3D goggles work because one eye receives light waves vibrating along the horizontal plane while the other eye receives the light vibrating along the vertical plane.

‘Polarisers’

Before Land, researchers built components to control polarisation from rock crystals, which were assigned almost magical names and properties, though they merely decreased the velocity or amplitude of light waves travelling at specific orientations. Land created “polarisers” by growing small crystals and embedding them in plastic sheets, altering the light passing through depending on its orientation in relation to the rows of crystals. His inexpensive polariser made it possible to reliably and practically filter light so only wavelengths with a particular orientation would pass through.

Land founded Polaroid in 1937 to commercialise his new technology. His sheet polarisers found applications ranging from the identification of chemical compounds to adjustable sunglasses. Polarising filters became standard in photography to reduce glare. Today the principles of polarised light are used in most computer and cellphone screens, to enhance contrast, decrease glare and even turn on or off individual pixels.

Polarizing filters help researchers visualise structures that might not be seen otherwise — from astronomical features to biological structures. In my own field of vision science, polarisation imaging localises classes of chemicals, such as protein molecules leaking from blood vessels in diseased eyes. Polarisation is also combined with high-resolution imaging techniques to detect cellular damage beneath the reflective retinal surface.

Before the days of high-speed digital capture of data and affordable high-resolution displays, or use of videotape, Polaroid photography was the method of choice to obtain output in many scientific labs. Experiments or medical tests needed graphical or pictorial output for interpretation, often from an analogue oscilloscope which plotted out a voltage or current change over time. The oscilloscope was fast enough to capture key features of the data — but recording the output for later analysis was a challenge before Land’s instant camera came along.

A common example in vision science is the recording of eye movements. A research study reported in 1960 plotted light reflected from an observer’s moving eye on an oscilloscope screen, which was photographed with a mounted Polaroid camera — not unlike the consumer Polaroid camera a family might pull out at a birthday party.

For decades, research labs and medical facilities have used setups consisting of a Polaroid camera and a mounting rig to collect electrical signals displayed on oscilloscope screens. The format sizes are less than dazzling compared to modern digital resolutions, but they were revolutionary at the time.

In 1987, with the founding of my new retinal imaging laboratory, there was no inexpensive method to provide sharable output of our novel images. After a few years of struggling to obtain high-quality output for conferences and publications, Polaroid came to our rescue with the donation of a printer, allowing our scientific contributions to reach an audience beyond our lab.

Land’s contributions go beyond patenting over 500 innovations and inventing products that millions purchased. His understanding of the interaction of light and matter promoted novel ways of characterising chemicals with polarised light. And he provided insights into the workings of the human visual system that had seemed to defy the laws of physics, coming up with what he called the Retinex theory of colour vision to explain how people perceive a broad range of colour without the expected wavelengths being present in the room.

Despite his brilliance, Land’s Polaroid eventually hit hard times in the decades after his death in 1991. Heavily invested in its film sales, Polaroid wasn’t prepared as all tiers of the imaging market went digital, with everyone from consumer photographers to high-end medical and optical imagers abandoning film and processing.

But rather than sink with the film market, Polaroid reinvented itself with new products that could help output the new world of digital images. And in a case of history repeating itself, Polaroid and other manufacturers of instant cameras are enjoying renewed popularity with younger generations who had no exposure to the original versions. Just like little Jennifer Land, plenty of people today still want a tangible version of their pictures, right now.![]()

- Written by Ann Elsner, professor of optometry at Indiana University

- This article was originally published on The Conversation