Sheryl Sandberg once remarked that she felt she was put on earth to scale organisations — and during her career as one of the most powerful executives in Silicon Valley, she plowed straight towards that grandiose vision. As an advertising head at Google in the mid-2000s, and as chief operating officer at Facebook for 14 years until her resignation on Wednesday, Sandberg oversaw a period during which the Internet services ballooned to colossal sizes, fed by a seemingly endless fountain of advertising revenue.

Though Sandberg may get most of her name recognition from Lean In — her 2013 blockbuster book encouraging women to take charge in the workplace — her most significant and complicated legacy may be the tech industry’s reliance on personalised advertising, which created both profits and complex nightmares at immense scale.

Sandberg was one of the people who made Google’s ad business so enormous that it became an essential part of every advertiser’s budget. Then, after she joined Facebook in 2008, four years after it was created, she brought that same self-service model to the social networking company, now called Meta Platforms. Instead of targeting users based on their search queries like Google did, Facebook could target based on what it gleaned of their personal identities, connections and interests. An entire industry of other tech companies followed suit with business models that offered products for free and made money off of users’ personal data instead.

“Sheryl had a front-row seat at the two largest and most successful advertising platforms in history,” said Patrick Keane, CEO of Action Network, a sports media firm, who worked with Sandberg at Google in the early aughts. Colin Sebastian, an analyst at Robert W Baird & Co, wrote that Sandberg’s lasting impact is the success of that advertising model: “Her legacy, in our view, is that Meta has one of the strongest business models in the digital economy.”

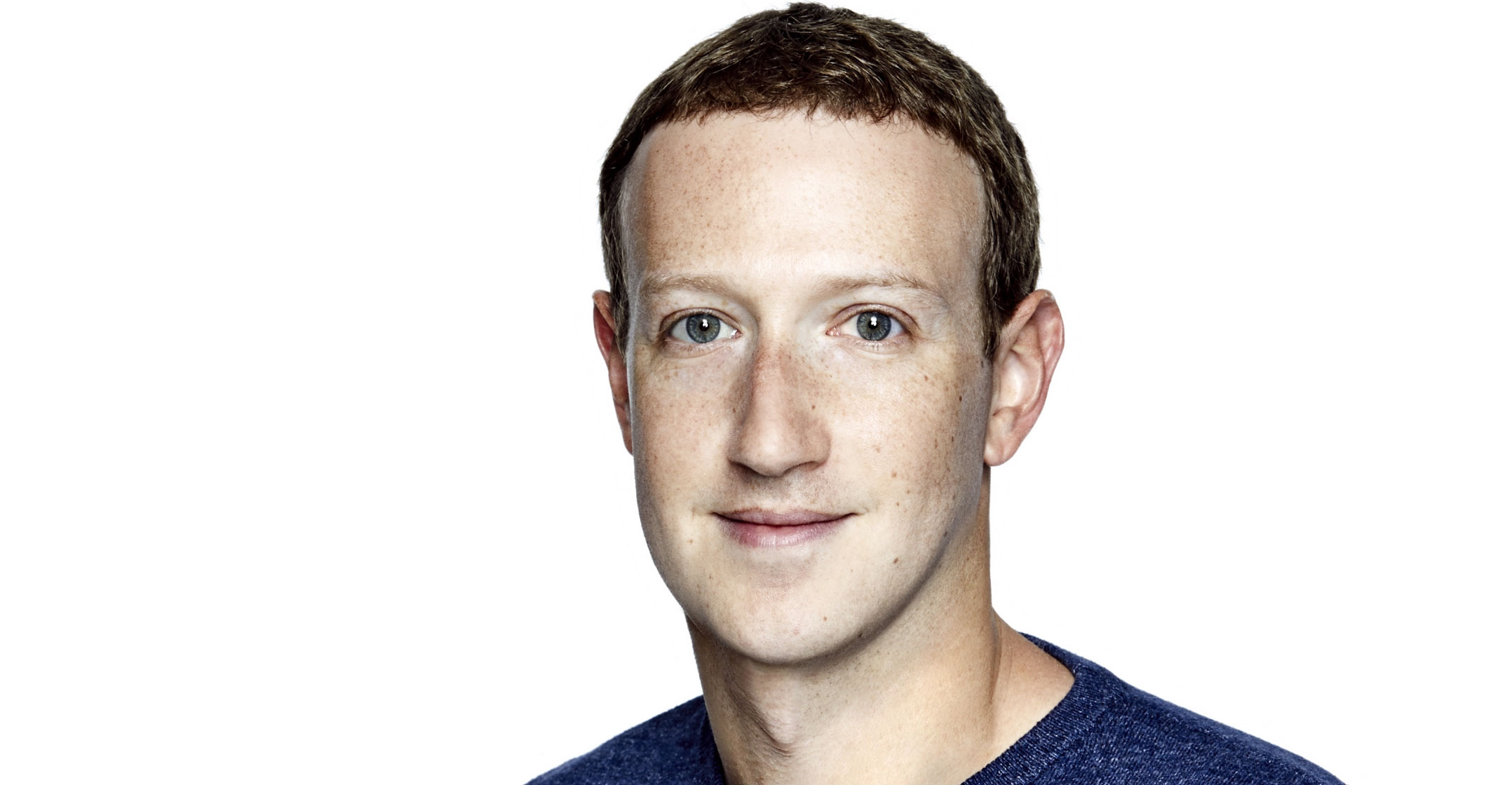

In recent years, Sandberg’s public image was tarnished alongside the mounting criticisms against Facebook, where she was widely seen as a powerful number-2 executive. Her expertise in legal, operations and policy complemented CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s preference for product, engineering and forward-looking technologies like virtual reality. In its earlier years, the social network was praised for its size and its “move fast and break things” disruptor attitude, but over time it was increasingly rebuked for its failure to rein in large-scale misinformation, hate speech, privacy breaches and lies from political dictators on its ever-expanding online platforms.

Scandals

US lawmakers frequently hauled Sandberg and Zuckerberg in front of congress to interrogate them on, among other things, foreign interference in elections and losing track of users’ personal data. The scandals never seemingly stopped: fomenting ethnic violence in Myanmar and Sri Lanka, allowing violent video and pandemic misinformation to go viral, and abetting the organisation of a right-wing insurrection at the US Capitol in 2021.

Sandberg was personally critiqued by Facebook employees for surrounding herself with trusted lieutenants who filtered bad news, and failing to address problems until they developed into public crises — and then treating them as reputational, as opposed to opportunities for substantial change at the company, people familiar with her leadership have said in the past. Most recently, the Wall Street Journal reported that she used her power at Facebook several years ago to suppress news about her then-boyfriend, though Meta says an internal investigation into the incident is not the reason for her departure.

The scale Sandberg sought for so many years is now the most scrutinised part of her legacy, by those who say she pursued growth single-mindedly without pausing to consider its repercussions. “It has been proven that the way Facebook scaled recklessly, intentionally, to dominate the entire global way that we communicate — it’s exactly that reckless ability to scale that ended up causing so much chaos and actual harm in many places,” said Yael Eisenstat, founder of Kilele Global, a tech and democracy advisory firm, who in 2018 headed the elections integrity team for political ads at Facebook. “I’ve never seen an ounce of self-awareness from her that she played any role in that.”

That embattled image stands in contrast to Sandberg’s beatific personal brand as a leading woman in the workplace, someone who balanced raising a family with unyielding career ambitions. News outlets dissected her personal schedule, which had rules like leaving work at 5.30pm to eat dinner with her kids every night and practicing what she called “ruthless prioritisation”. Her exhortation to career-driven women to “lean in” and examine where they were holding themselves back in male-dominated companies sold millions of copies. Across the world, women invoked the lessons of Lean In or thought to themselves, “Sheryl told me to,” when negotiating for a raise or strategising for career growth. The book evolved from a TED talk and turned into a network of “Lean In” in-person groups around the world — then, as the phrase became overused, it deflated into a punchline. Some readers valued her candour and her emphasis on taking charge, while others felt that her advice rang hollow because her wealth and other privileges made it easier for her to proclaim that her tips worked.

That embattled image stands in contrast to Sandberg’s beatific personal brand as a leading woman in the workplace, someone who balanced raising a family with unyielding career ambitions. News outlets dissected her personal schedule, which had rules like leaving work at 5.30pm to eat dinner with her kids every night and practicing what she called “ruthless prioritisation”. Her exhortation to career-driven women to “lean in” and examine where they were holding themselves back in male-dominated companies sold millions of copies. Across the world, women invoked the lessons of Lean In or thought to themselves, “Sheryl told me to,” when negotiating for a raise or strategising for career growth. The book evolved from a TED talk and turned into a network of “Lean In” in-person groups around the world — then, as the phrase became overused, it deflated into a punchline. Some readers valued her candour and her emphasis on taking charge, while others felt that her advice rang hollow because her wealth and other privileges made it easier for her to proclaim that her tips worked.

She delivered commencement addresses in which she told graduates to “bring your whole self to work” and “be authentic” in your professional life. On Facebook, she posted updates about the importance of mental health. When Hillary Clinton ran for president, it even seemed possible that Sandberg could be nominated to be treasury secretary (Larry Summers, who’d held the post in the past, had been a mentor). After Sandberg’s husband, SurveyMonkey CEO Dave Goldberg, died unexpectedly in 2015, she channelled her own maxims about authenticity and wrote a second book, Option B, which wove together her grief with stories of how adversity can spur growth and resilience. “Sheryl’s books have made a big impact on people,” said Kim Scott, who reported to Sandberg at Google and included anecdotes from that experience in her management book Radical Candor. “When someone like Sheryl is willing to make herself vulnerable and share mistakes she made, it helps everybody.”

Her leadership style has also become the stuff of lore. “One of the great things about working for Sheryl is she never wasted a minute of anyone’s time — her own or anyone else’s,” Scott said. “She was really, really focused on getting things done.”

One of the great things about working for Sheryl is she never wasted a minute of anyone’s time — her own or anyone else’s

Dan Rose, a venture capitalist who worked for Sandberg for over a decade, wrote on Twitter that Sandberg “loved everything about scaling” and was “a demanding boss who held me to a high standard” — someone who pushed him hard but also celebrated him and inspired lifelong loyalty.

Sandberg not only built out the company’s money-printing business model, she also oversaw its public policy team, which increasingly became a lightning rod for controversy around perceived censorship, misinformation and controversies over training politicians who later used Facebook to manipulate the public. Katie Harbath, a former Facebook public policy director and Republican aide, said that Sandberg was “incredibly instrumental” in building up the company’s roster of employees directly managing those issues. In 2011, both she and Joel Kaplan, who eventually became the company’s top Republican and vice president of global policy, were hired at the company. “Sheryl was very good at looking around corners, thinking a bit longer term,” Harbath said. “Early on, Mark didn’t want to be part of the public policy side very much.”

That dynamic changed in recent years, Harbath acknowledged, as Zuckerberg took a heavier hand at the company. Those who could see the leadership dynamic shift suspected Sandberg might leave eventually. “I don’t think it’s much of a surprise for folks internally, but it is a big change, and it’s a symbolic change,” Harbath said.

Sandberg hasn’t said much about what she’ll do next apart from focusing on her family and philanthropy. As Facebook’s troubles accumulated, it became harder for Sandberg to work on women’s empowerment or other causes without bringing over baggage from her main job, said two people who worked closely with her at Facebook, who asked not to be named because they’re not authorised to speak on the subject publicly. “It was the elephant in the room,” one of the people said. She also would like to distribute her wealth to causes important to her without concern about whether the moves would create a perception of bias at Facebook, the other person said.

Eisenstat, the former head of Facebook’s elections integrity team, said that in her opinion, Sandberg can’t just be responsible for the economic outcomes of her career — her legacy must also be examined for its impact on society. “Leaving Facebook in no way absolves her of any of the decisions that were made under her watch,” Eisenstat said. “People are going to try to rewrite her history now. But it doesn’t change any of that.” — Ellen Huet and Davey Alba, (c) 2022 Bloomberg LP