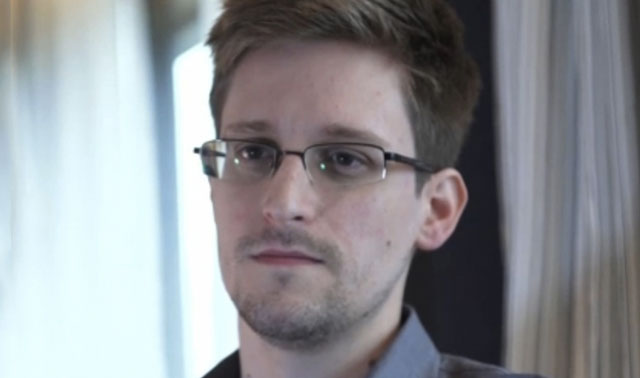

Edward Snowden is increasingly unhappy with the situation in Russia, where he has lived for more than three years. President Vladimir Putin once welcomed the National Security Agency contractor for his propaganda value, but he may be wondering if it’s all been worth it.

Snowden arrived in Moscow in June 2013. That was almost a year before the Crimea annexation, and Russia could still try to sell itself to radical leftists who admired Snowden as the lesser evil, compared with the Big Brother US. Putin talked a lot about Snowden showing obvious delight for thumbing his nose at the US, which had tried to intercept the whistle-blower. He described Snowden as a “weird guy”, an idealist, who was safe in Russia even though he had no secrets to pass on.

After Crimea, though, such statements started to appear hollow. “Russia is not the kind of country that hands over fighters for human rights,” Putin said at the St Petersburg Economic Forum in May 2014. That the Russian president could talk about human rights after faking a secession referendum in Crimea would have been funny if it weren’t so manipulative.

Snowden appeared to play along. In 2014, he took part in Putin’s carefully stage-managed and scripted annual call-in show, asking the Russian leader whether Russia intercepted, stored and analysed its citizens’ electronic communications. Putin said Russia used advanced technology to fight terrorism. “But we do not allow ourselves to use it on a mass scale, in an uncontrolled way,” he added. “I hope, I very much hope, that we never will.”

Snowden defended what appeared to be a softball question in a column for The Guardian, saying that he had “sworn no allegiance” to Russia and that he would fight total surveillance everywhere. The Guardian article helped him maintain credibility among Western radicals.

On several other occasions, Snowden criticised Russia for its treatment of homosexuality and for attacks on Internet freedoms, but the Kremlin was unconcerned. “These are rather arguable statements, but he has his point of view,” Putin’s press secretary, Dmitri Peskov, said last year. “Yes, he lives in Russia, but it doesn’t mean anything is being imposed on him.”

In recent months, though, Snowden has stepped up his harsh criticism of Russian ways: it became clear to him that Putin had lied during that call-in show.

The NSA leaker took to Twitter in July, when the Russian parliament was passing the so-called “Yarovaya package” — a fiercely repressive set of laws aimed at establishing total control over Russians’ online communications. Internet providers and mobile operators are expected to record and store all conversations and message exchanges for six months, and their metadata for three years. Internet companies are obliged to help the Russian secret police decrypt any encrypted communication. Snowden’s condemnation was vehement:

@Snowden: Signing the #BigBrother law must be condemned. Beyond political and constitution consequences, it is also a $33b+ tax on Russia’s internet.

@Snowden: #Putin has signed a repressive new law that violates not only human rights, but common sense. Dark day for #Russia.

The Yarovaya package is harsher than any electronic surveillance legislation in the US, because the Russian measures openly tell citizens that their communications will be monitored pretty much at the discretion of the intelligence services. It embodies all the abuses that Snowden has opposed.

Three years is enough time to understand Russian politics a little better, and Snowden appears to be interested in more than his professional area. On Wednesday, he tweeted about the recent news that Russia’s last remaining big independent pollster, the Levada Centre, has been designated a “foreign agent”, along with some of Russia’s strongest human rights organisations, for accepting foreign research grants.

@Snowden: The effort to classify @Levada_RU and #Memorial as “foreign agents” confirm our worst fears about this terrible law.

Levada received the designation after publishing a poll that showed Putin’s United Russia losing support ahead of the 18 September parliamentary elections. Snowden now openly criticises the Kremlin on matters of political importance, such as its “anti-terrorism” policy and its own special brand of electoral democracy. The whistle-blower tweets in English, but Russian media, including pro-Kremlin ones, invariably pick up his posts.

I would be surprised if the Kremlin weren’t irritated. It does its best to squeeze local critics out of the country or discredit them, yet it’s stuck harbouring a foreigner whose initial gratitude may have worn out and who is less willing to give Putin the benefit of the doubt.

Snowden has tweeted that he fears retaliation for his criticism, but he won’t desist. There aren’t too many ways for the Kremlin to retaliate, though, without handing a moral victory to the US. It certainly won’t extradite Snowden: in March, when Donald Trump called for the return of the whistle-blower, Peskov said the Russian government’s position hadn’t changed. It would be no surprise, however, if arrangements were quietly made to move Snowden to another asylum country. With his zealotry, he is a liability to Putin, and he may never really have been an asset. — (c) 2016 Bloomberg LP