There was a time when the spacey melody of Rodriguez’s Sugar Man hung permanently in the air at university digs around SA, as much a part of the atmosphere as the curling cigarette smoke and the pungent scent of incense. More than The Rolling Stones or The Sex Pistols, Rodriguez was the soundtrack of rebellion for liberal young whites chafing under a conservative apartheid government.

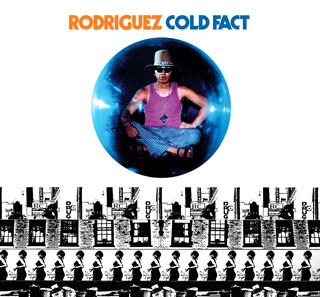

The blue-collar American musician’s album Cold Fact found its way to SA shortly after its release in the early 1970s, building an enduring fan base that lasted through to the mid-1990s. His music was kept alive as older brothers passed their scratched vinyl copies down to siblings and bootleg C60 cassettes (Cold Fact was just a minute too long to fit on one side) were shared among friends. Analogue file-sharing.

No one knew much about the folk singer they called Jesus Rodriguez other than that he was a genius and that he had made a record more important than Blonde on Blonde or What’s Going On. Searching for Sugar Man chronicles the story of how two SA fans searched for the truth of Rodriguez’s fate and ended up bringing him here to play his music to his fans.

It is the sort of fairy tale that could only have played out before the Internet and perhaps only in a country as cut off from the rest of the world as apartheid SA. Rodriguez — sitting cross-legged and staring from behind his trademark shades on the cover of Cold Fact — was a mystical figure cloaked in rumour and shrouded in urban legend.

Everyone thought he was dead – one of the most widely believed stories was that he sang Forget It (“Thanks for your time / then you can thank me for mine”) as his suicide note and epitaph before blowing his brains out on stage. Then, suddenly, he arose from the grave to do concerts at the Standard Bank Arena in 1998, an event as symbolic of the end of decades of isolation as the 1995 Rugby World Cup.

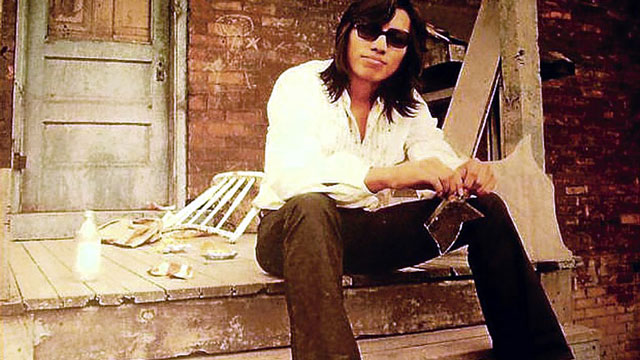

Swedish director Malik Bendjelloul shows how journalist Craig Bartholomew-Strydom and record shop owner Stephen “Sugar” Segerman set out in the late 1990s to find out what had really happened to their hero. Something that would be a quick search on Facebook today takes them months of detective work. They eventually track him down to his hometown of Detroit where he languishes in obscurity and makes his living doing manual labour.

What emerges is an interesting slice of SA cultural history as well as a fascinating tale of the rock star that almost made it. It’s not surprising, hearing the man’s music again, that he was so big in SA, but it is confounding that he never made as big anywhere else. He was not as brilliant as the chameleon Bob Dylan, but he was also less oblique and more authentic.

His songs of social injustice and urban decay were poetic yet grounded, direct but open to interpretation. Some of his lyrics were stinging rebukes or angry snarls, but he was never quite as mean as Dylan. And he sang his verses in a lilting voice, backed by spare and inventive arrangements. One can’t but wonder what he might have achieved had his career not been cut short.

As the film chronicles — speaking to fans, the man’s family, his record promoters and producers along the way — people expected big things from Cold Fact upon its release in 1970. The record got good reviews but it sold poorly. Rodriguez was dropped by his record label when his second album Coming from Reality also bombed. Perhaps foreseeing his failure, he sang: “The sweetest kiss I ever got is the one I’ve never tasted.”

Two-and-a-half decades later, he is astonished to find out that he has sold perhaps half a million records in SA because he has not seen a cent of the royalties. His concerts sell out and he is as amazed and delighted as Spinal Tap when they find out they’re big in Japan. SA fans are equally surprised to find out that Rodriguez is alive and that the rest of the world never acknowledged his brilliance.

There’s a lot here that intrigues, including some archival footage of verkrampte 1970s SA and interviews with the Voëlvry musicians so influenced by Rodriguez. A visit to the apartheid era archives — where there is still a vinyl copy of Cold Fact with drug paean Sugar Man neatly scratched to make it unplayable — reminds us that PW hated pop as much as Putin loathes Pussy Riot.

There’s also a view of American city life we don’t see often in the urban decay of Detroit in a post-industrial world. And of course, the enigmatic Rodriguez is right at the centre of the film. He does not give much of himself besides his laconic charm, remaining as mysterious at the end of the film as he was at the beginning.

Enjoyable as Searching for Sugar Man is, there are a couple of points about the film that irked me. Like many documentaries of late, Sugar Man is quick to throw out any facts that might interfere with the dramatic narrative arc it develops. It’s a form of dishonesty that makes one question every other fact the film presents.

Just as one example, Rodriguez didn’t completely disappear until 1998, but appeared for a few gigs at medium-sized venues in Australia in the late 1970s. Yes, Australians also loved Rodriguez, though not as much as South Africans. You wouldn’t know this from Bendjelloul’s storytelling – which is unfortunate since his film seems likely to become the accepted record of the facts.

Also, Bendjelloul should have tipped his hat in the direction of the makers of Looking for Jesus, a heartfelt but amateurish SA film produced by Sugar that explored the same topic. The new film is far superior because of its access to Rodriguez and its bigger budget, but the similarities are so glaring that they can’t pass without comment.

Yet despite those faults, Searching for Sugar Man succeeds as a rockumentary about a failed musician, as a look at the way music changes the world, and as a window into a side of the US we don’t often see on film. It’s as bittersweet as Rodriguez’s music – so perhaps it is truthful in the way that really matters. — (c) 2012 NewsCentral Media