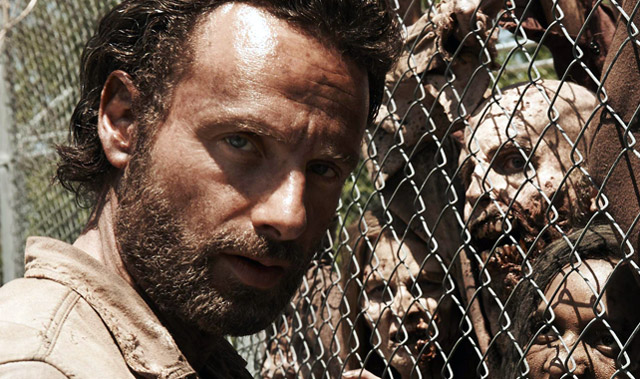

If you watch the upcoming season 5 finale of The Walking Dead, the story will likely evoke events from previous episodes, while making references to an array of minor and major characters. Such storytelling devices belie the show’s simplistic scenario of zombie survival, but are consistent with a major trend in television narrative.

Prime time television’s storytelling palette is broader than ever before, and today, a serialised show like The Walking Dead is more the norm than the exception. We can see the heavy use of serialisation in other dramas (The Good Wife and Fargo) and comedies (Girls and New Girl). And some series have used self-conscious narrative devices like dual time frames (True Detective), voice-over narration (Jane the Virgin) and direct address of the viewer (House of Cards). Meanwhile, shows like Louie blur the line between fantasy and reality.

Many have praised contemporary television using cross-media accolades like “novelistic” or “cinematic”. But we should recognise the medium’s aesthetic accomplishments on its own terms. For this reason, the name I’ve given to this shift in television storytelling is “complex TV”.

There are a wealth of facets to explore about such developments (enough to fill a book), but there’s one core question that seems to go unasked: “Why has American television suddenly embraced complex storytelling in recent years?”

To answer, we need to consider major shifts in the television industry, new forms of television technology, and the growth of active, engaged viewing communities.

We can quibble about the precise chronology, but programmes that were exceptionally innovative in their storytelling in the 1990s (Seinfeld, The X-Files, Buffy the Vampire Slayer) appear more in line with narrative norms of the 2000s. And many of their innovations — season-long narrative arcs or single episodes that feature markedly unusual storytelling devices — seem almost formulaic today.

What changed to allow this rapid shift to happen?

As with all facets of American television, the economic goals of the industry is a primary motivation for all programming decisions.

For most of their existence, television networks sought to reach the broadest possible audiences. Typically, this meant pursuing a strategy of mass appeal featuring what some derisively call “least objectionable programming”. To appeal to as many viewers as possible, these shows avoided controversial content or confusing structures.

But with the advent of cable television channels in the 1980s and 1990s, audiences became more diffuse. Suddenly, it was more feasible to craft a successful programme by appealing to a smaller, more demographically uniform subset of viewers — a trend that accelerated into the 2000s.

In one telling example, Fox’s 1996 series Profit, which possessed many of contemporary television’s narrative complexities, was cancelled after four episodes for weak ratings (roughly 5,3m households). These numbers placed it 83rd among 87 prime time series.

Yet today, such ratings would likely rank the show in the top 20 most-watched broadcast programmes in a given week.

This era of complex television has benefited not only from more niche audiences, but also from the emergence of channels beyond the traditional broadcast networks. Certainly HBO’s growth into an original programming powerhouse is a crucial catalyst, with landmarks such as The Sopranos and The Wire.

But other cable channels have followed suit, crafting original programming that wouldn’t fly on the traditional “big four” networks of ABC, CBS, NBC and Fox.

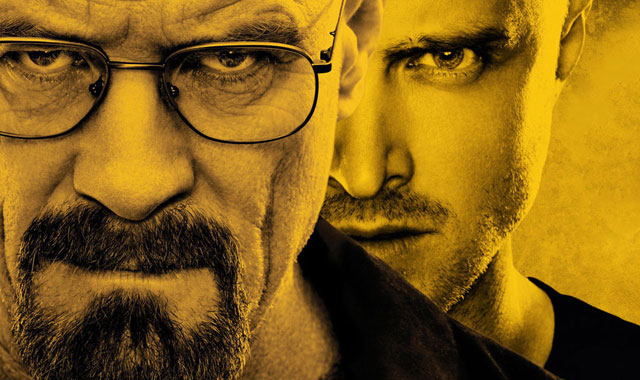

A well-made, narratively complex series can be used to rebrand a channel as a more prestigious, desirable destination. The Shield and It’s Only Sunny in Philadelphia transformed FX into a channel known for nuanced drama and comedy. Mad Men and Breaking Bad similarly bolstered AMC’s reputation.

The success of these networks has led upstart viewing services like Netflix and Amazon to champion complex, original content of their own — while charging a subscription fee.

The effect of this shift has been to make complex television a desirable business strategy. It’s no longer the risky proposition it was for most of the 20th century.

Miss something? Hit rewind

Technological changes have also played an important role.

Many new series reduce the internal storytelling redundancy typical of traditional television programmes (where dialogue was regularly employed to remind viewers what had previously occurred).

Instead, these series subtly refer to previous episodes, insert more characters without worrying about confusing viewers, and present long-simmering mysteries and enigmas that span multiple seasons. Think of examples such as Lost, Arrested Development and Game of Thrones. Such series embrace complexity to an extent that they almost require multiple viewings simply to be understood.

In the 20th century, rewatching a program meant either relying on almost random reruns or being savvy enough to tape the show on your VCR. But viewing technologies such as personal video recorders, on-demand services and DVD box sets have given producers more leeway to fashion programmes that benefit from sequential viewing and planned rewatching.

Like 19th century serial literature, 21st century serial television releases its episodes in separate instalments. Then, at the end of a season or series, it “binds” them together into larger units via physical boxed sets, or makes them viewable in their entirety through virtual, on-demand streaming. Both encourage binge watching.

Giving viewers the technology to easily watch and rewatch a series at their own pace has freed television storytellers to craft complex narratives that are not dependent on being understood by erratic or distracted viewers. Today’s television assumes that viewers can pay close attention because the technology allows them to easily do so.

Shifts in both technology and industry practices point toward the third major factor leading to the rise in complex television: the growth of online communities of fans.

Today there are a number of robust platforms for television viewers to congregate and discuss their favourite series. This could mean participating in vibrant discussions on general forums on Reddit or contributing to dedicated, programme-specific wikis.

As shows craft ongoing mysteries, convoluted chronologies or elaborate webs of references, viewers embrace practices that I’ve termed “forensic fandom”. Working as a virtual team, dedicated fans embrace the complexities of the narrative — where not all answers are explicit — and seek to decode a programme’s mysteries, analyse its story arc and make predictions.

The presence of such discussion and documentation allows producers to stretch their storytelling complexity even further. They can assume that confused viewers can always reference the Web to bolster their understanding.

Other factors certainly matter. For example, the creative contributions of innovative writer-producers like Joss Whedon, JJ Abrams and David Simon have harnessed their unique visions to craft wildly popular shows. But without the contextual shifts that I’ve described, such innovations would have likely been relegated to the trash, joining older series like Profit, Freaks and Geeks and My So-Called Life in the “brilliant but cancelled” category.

Furthermore, the success of complex television has led to shifts in how the medium conceptualises characters, embraces melodrama, reframes authorship and engages with other media. But those are all broader topics for another chapter — or, as television frequently promises, to be continued.![]()

- Jason Mittell is professor of film and media culture at Middlebury College

- This article was originally published on The Conversation