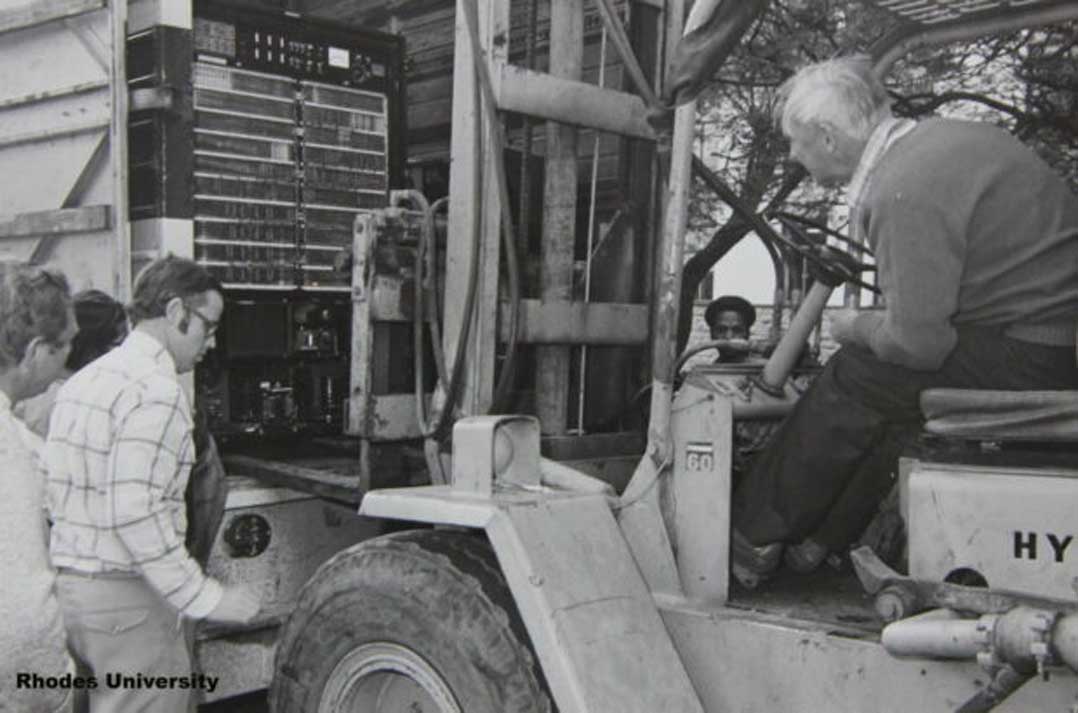

In 1965, Rhodes University bought its first computer – a gigantic beast that cost millions of rands, weighed more than five tons and boasted 4.8 whole kilobytes of memory. The ICT 1301 Transistorised Computer was carefully hauled up to the top of the physics building using a pulley and an I-beam. It was only the second computer ever to be installed at a South African university. (The first was at Wits.)

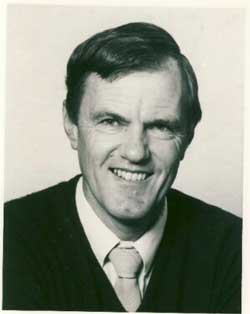

Professor Emeritus Pat Terry, then a final year physics and applied mathematics student, remembers the day the 1301 arrived in Grahamstown (now Makhanda).

“We were all desperate to see what this thing looked like, but we weren’t allowed into the building because of physics prac exams. As soon as we were allowed in, I charged up the stairs with a few other guys and we found Mike Lawrie, dressed in a mechanic’s overall, wielding a shifting spanner, busy bolting parts of this huge machine together. It filled the whole top floor.”

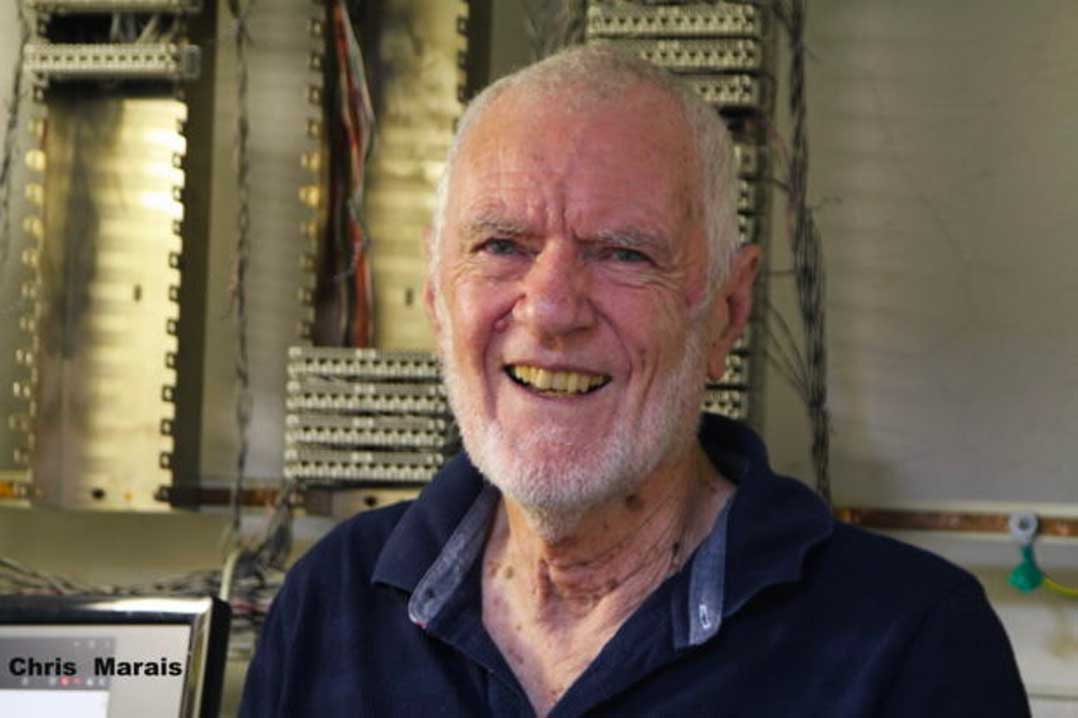

Mike Lawrie was the resident engineer, who came as ”part of the deal” with the computer. While studying for his BSc part time, Lawrie kept the 1301 running smoothly, often with two hammers, which he still owns.

“If there was a fault, you’d put the wooden side of one hammer against a circuit board, and you take the other hammer and you go tap-tap-tap, trying to shake up anything loose.”

Prof Pat Terry added: “If part of the circuitry went wrong, Mike Lawrie would get his soldering iron and replace it when he’d found the faulty piece. It was real discrete electronics. None of this modern stuff where at the first sign of a glitch you throw it away and buy a new computer.”

The era of clankety-bonk

The first mainframes all worked on punched cards.

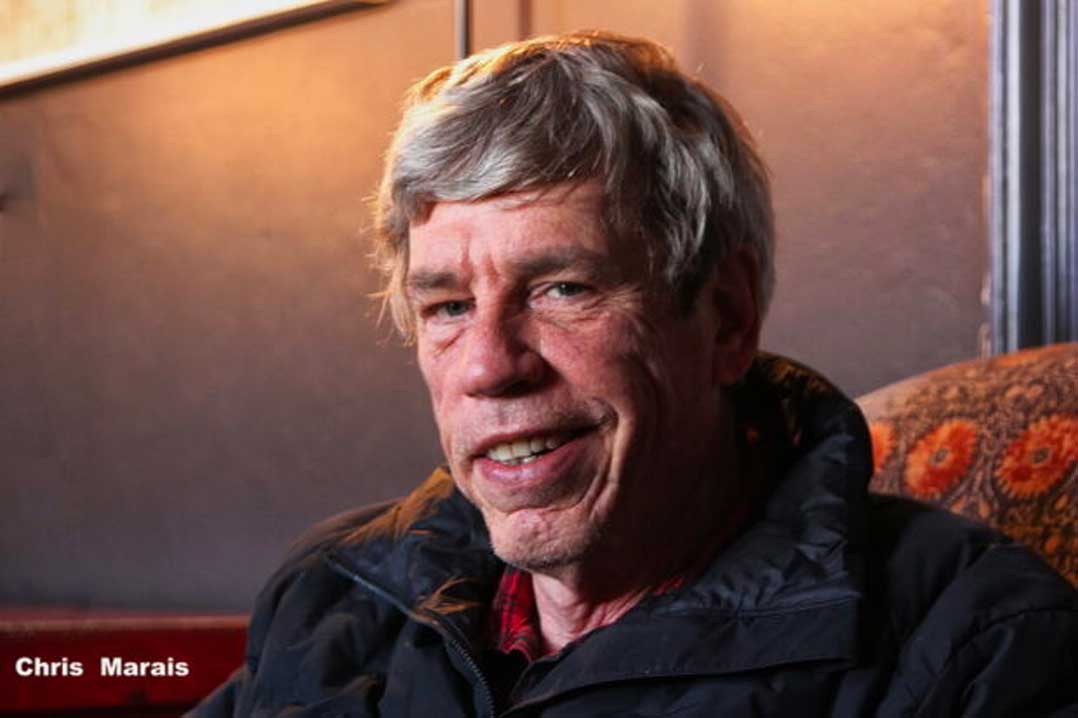

François Jacot-Guillarmod (known to all as Jacot) was one of the first computer science students when the course and department started at Rhodes University in 1970.

“The decks of punched cards representing your program and data were unmarked in the early days, so you had to become adept at interpreting the holes in the card and reverse engineering its contents. Most packs were a few centimetres thick, but as your skills and ambitions advanced, they got bigger and bigger, up to 20cm or 30cm thick – a real ‘cart-astrophe’ if they dropped.”

Those old computers were also loud. “It was the time of clankety-bonk,” said Lawrie. “The spinning disk drives were big things. It was like watching your washing go round and round.

“But we managed to have fun with them, far more so than other universities where they locked their computers away and didn’t let students near them,” he added. “I felt the computers were there to be used. Otherwise they’d be obsolete before they were worn out.”

In 1967, Lawrie, Terry and a physics master’s student called Howard Williams teamed up to deploy the computing powers of the 1301 for the purposes of a “dating app”.

“We drew up a questionnaire, and you had to describe yourself in five points,” said Lawrie. “Then the computer gave you a list of five or 10 names of the opposite sex that you might care to invite to the Arts and Science Ball. It was only a bit of fun, but was it a hit! We were the first computer dating service. The students lined up to get their printouts.”

The hallowed machine

Deputy vice chancellor of research and innovation Peter Clayton, who retired at the end of 2022, remembers how things were when he started his computer science, physics and mathematics studies as an undergraduate student in 1976.

“Of course, it wasn’t like anyone could just stroll into the computer room. The machine was worth millions of rand. Other institutions wouldn’t allow you in the same room. You might be allowed to look through a window at this hallowed machine.

“But at Rhodes, as long as you did Mike Lawrie’s ‘learners’ and ‘drivers’ course, it was fine. You had to know the basics and work under an operator for a while, then you got your ‘driver’s licence’. You considered it a privilege when Mike would schedule you to go and sit with the computer at three in the morning. It gave you street cred like you won’t believe.”

Heaven on a screen

Mike Lawrie left as resident engineer in 1969, returning to Rhodes in 1971 as director of computing services.

Computer terminals were cripplingly expensive at the time, but in the late 1970s Lawrie hunted down some screens in the UK at the fraction of the normal price, and Rhodes University’s team fiddled until they could be made to work.

“Gee, the students liked it,” recalled Lawrie. “You could sit in front of a screen, you’ve got some file space on the computer, and it was heaven. This was an advance no other South African university was making available to their students.”

Clive Way-Jones, then head of the electronic services unit in the physics department, observed that the terminals worked thanks to simple pulses down a wire, and was the first to wonder whether they might work over a longer distance. He suggested to Lawrie they try putting up a cable between the physics department and the Struben Computing Centre across the road.

“We tested the signals using an oscilloscope, and they worked perfectly,” said Lawrie.

The next big question was: how long could the wires be? It so happened that SA Posts and Telecommunications, soon to become Telkom, had installed telephone cabling throughout the town. Lawrie prevailed upon them to link the Struben Centre to his home in Ilchester Road, just over 2km away.

This also worked perfectly. From then on, Lawrie and an ever-increasing number of Rhodes University staffers were able to work from home, for the negligible cost of a local lead wire.

Again, nothing remotely like this had been attempted anywhere else in South Africa.

Gyppos, workarounds and the Cyber

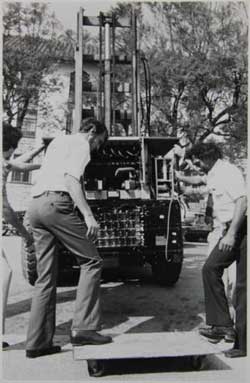

In 1981, the last of the ICL mainframes was removed, and in came a smaller, exciting and far more powerful new computer – Control Data Corporation’s Cyber 825.

It cost the University R800 000.

Lawrie and his team were thrilled to find that, unlike an IBM or a Univac or a Burroughs, there were no proprietary peripheral issues.

“The manual said: if you have IBM terminals, plug them in like this. Burroughs terminals, plug them in like that, Univac terminals, glass teletypes, PCs? Here’s how to connect them. Help yourself. By absolute luck, we were geared for networking.”

As Peter Clayton pointed out: “The whole culture here was one of gyppos and adapting and workarounds. The lack of budget was an enabler.”

Lawrie and his team devised a simple form of e-mail. It wasn’t a big deal, he said.

“We had to write code – some of it in Cobol – to make it work for the Cyber, but it was fine. Store the mail, send the mail, receive it, reformat it, handle it. So, I could send emails to my staff. Sometimes they would even read them.”

Plato and The Fixers

The Cyber had another advantage. It came with an online learning programme called Plato (Programmed Logic for Automatic Teaching Operations), which Lawrie helped spread to various schools and institutions as far away as Cape Town, Johannesburg and Bhisho.

Rhodes got lucky when JCI (a finance company) upgraded and donated its lightly used CDC Cyber 825 to the university for the modest cost of reconfiguring and transport.

“This was a blessing. We moved the Plato computer-based education systems onto that second Cyber and used the first one as the main research and communications computer,” said Lawrie.

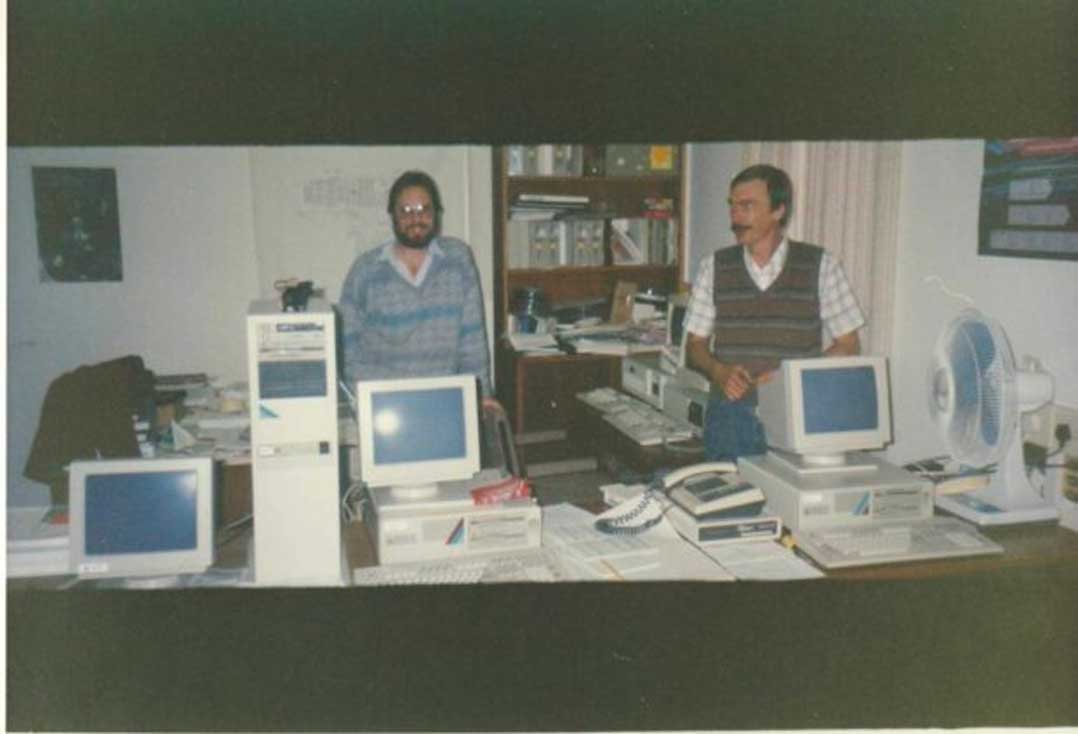

Jacot returned to the university in 1983 and became a systems programmer under Lawrie, alongside Dave Wilson, who joined a year later. It fell to Wilson and Jacot to keep the system working. They were The Fixers.

Jacot said: “Plato is how we cut our teeth on wider area networking. It involved schools and institutions all over the country. We managed to do things like getting 10 terminals in Bhisho linked to a school in Cape Town, that sort of thing, and we worked out how to do it quite cheaply, via Telkom lines.

“As a bonus, Plato had a messaging system, which meant that users in remote locations could leave messages for other users. This was before e-mails across a distance, but it enlightened us. Installing Plato’s networking hardware provided good experience in what was useful. And perhaps even more importantly, what was not.”

The computer says yes

In the mid-1980s, the physics department acquired a VAX mini-computer, roughly the size of a washing machine.

Prof Justin Jonas, now head of radio astronomy techniques and technology at the department, explained: “We needed the Starlink software package for radio astronomy, and it only ran on VAXes. The VAX, made by Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC), had an in-house networking system called DECNet, but it communicated only with other VAX machines.

“Because we were doing processing of radio astronomy and ionosphere data on both the Cyber and the VAX computers, we needed to shift data backwards and forwards across the existing terminal lines between Struben and the physics department. That’s how ‘internetworking’ between the Cyber and the VAX started,” said Jonas.

By then, most South African universities were using IBMs, and they only “spoke” with one another using a protocol called Network Job Entry (NJE), which was part of the IBM proprietary Systems Network Architecture. NJE later became the protocol used by Bitnet, a precursor to the eventual Internet protocol, TCP/IP, explained Jonas.

“But the VAX only ‘spoke’ DECNet and the Cyber only ‘spoke’ CDCNet. I had set up a simple file transfer system, but it provided very limited functionality. Mike looked around and found NJE emulators for both the VAX and the Cyber that would allow more sophisticated applications, and in short order he brought me a magnetic tape containing the Jnet NJE emulator. I installed Jnet on the VAX while Jacot, Dave and Mike installed the corresponding Cyber emulator. With very little hassle we had the two machines speaking to one another in a third machine’s language.”

The potential of e-mail

Meanwhile, up north in the old Transvaal, the University of the Witwatersrand, University of Pretoria, Potchefstroom University, the CSIR and the Foundation for Research and Development (FRD, which later became the National Research Foundation, or NRF) all had IBM computers and were networked to one another via dedicated lines – seldom used, according to Lawrie. He attended workshops with other universities and there struck up a friendship with Philip Welman of Potchefstroom University (Potch, now North West University).

The cultures of the two universities could not have been more different. Potch was politically conservative, and under normal circumstances in the 1980s would never have engaged in any form of official communication with a liberal, apartheid-opposing institution like Rhodes.

Lawrie and Welman ignored all politics and became good friends. They were both absolutely convinced that e-mails and digital connections were the way to go. Eventually, with help from Vic Shaw of the FRD, Rhodes connected to Potch via a stub line, so joining the network of IBM computers at Potch, Wits, UP and the FRD (then still part of CSIR).

Lawrie was completely fired up about the potential of e-mail, but he struggled to convince many others. Close friends and colleagues didn’t quite see the point of e-mails when you could just pick up the phone or walk down the corridor and knock on a door. And if that wasn’t possible, there was fax – then the absolute cutting edge of communication technology.

Professor Pat Terry confessed to being one of those Luddites.

Conspiring at rather high speed

After Terry had graduated with his PhD in physics from Cambridge, he returned in 1972 to join the department of applied mathematics under Prof Rolf Braae. Peter Clayton remembers Terry as being “young, hip and the exciting lecturer”.

In the 1980s, there were many computer languages, including Cobol, Fortran and Pascal. But Modula-2 was better for teaching purposes. Terry was on the international standardisation committee for it and needed to be in constant contact with the other members, as suggestions were made and decisions taken between eight-monthly workshops around the world.

Randy Bush, a software engineer from Portland, Oregon, remembers meeting this “tall, reserved but wry computer scientist from some strange place in South Africa. Prof Terry and I became friends, united against a common enemy – the forces of corruption and complication of an obscure computer language we both loved.”

He added: “In 1988, Pat visited me in my home, and asked me how it was that I and other peers seemed to be conspiring at rather high speed between meetings. I described low-cost computer networking to him.”

‘I’ve met the King of FidoNet’

As luck would have it, Randy Bush was the powerhouse behind a small but rather remarkable proto-e-mail network. Pat Terry explained:

FidoNet was run by enthusiastic amateurs, who have been responsible right through the history of computing, for doing all sorts of interesting things first. And they worked out how they could intermittently connect their computers onto a geographically distributed network. At three in the morning, I think it was, they had what was called Mail Hour. And at that stage, if you were part of the system, your computer had to be connected to its modem and standing by. The computers would literally phone one another up and squirt the e-mail down the phone line, using modems.

So, I came back from that conference with the software on a few precious floppy disks, as they were those days, and then discovered when I got here, that Dave Wilson had had recently managed to contact FidoNet and they were going to explore using this.

It was just marvellous to walk in and say: ‘I’ve met the King of FidoNet. He’s given us the software and he’s going to help us.’

By that stage, Mike Lawrie was beside himself with frustration. In the late 1980s, sanctions against the apartheid government reached new heights with America’s Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act. The University of Cape Town had managed to connect to the outside world for three weeks via UUNet before they were cut off. Academics from South African universities, even those opposing apartheid, were banned from attending overseas conferences.

Lawrie had tried everything to connect with the outside world digitally, and nearly got it right after contacting Bitnet. They had promised Lawrie they would not cut South Africa off. But those with power and money at the CSIR and the FRD said the cause was useless. Why bother? They would just be cut off again. Lawrie was infuriated by their apathy and lack of trust.

Nefarious and joyful

FidoNet then became the final hope for digital connection to the outside world, even though it was considered a bit of a “toy” system. The team quickly created code to route e-mails from the Cyber to the FidoNet node on a PC in Dave Wilson’s office.

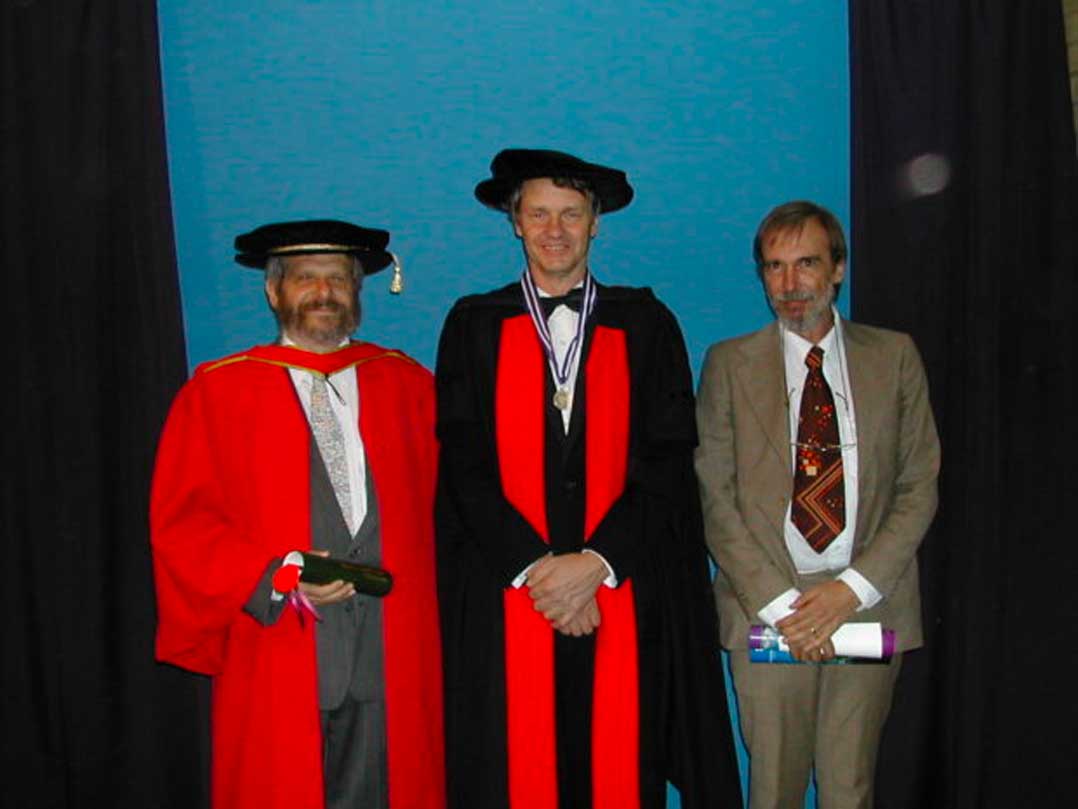

On 2 February 1989, they sent the first e-mail to Randy Bush from the Rhodes Cyber. As Bush recounted in 2002, on the occasion of his being awarded an honorary doctorate from Rhodes University:

In a few weeks, [Pat Terry] had it working. Soon he wrote to ask if a few of his academic colleagues could also use the net through our connection. I said sure. Within a very few months, use had spread through various parts of Rhodes, nefariously and joyfully propagated by Pat Terry, Jacot-Guillarmod and others.

For Mike Lawrie, the 22nd day after connection was even more significant.

“UCT had had their connection for three weeks before someone pulled the plug. No one pulled our plug, ever. That was a very good moment indeed. It was working, and it stayed working.”

As he later wrote in his techno-history of South Africa’s Internet: “We really could not believe that we had done better than this. We had broken through the sanctions barrier on a zero-budget operation without having to resort to any cloak-and-dagger exercises. We had also beaten the South African government of the day, which was desperately trying to control every last form of communication in and out of the country.”

Apartheid, and the unrepentant hippy

The Rhodes staff asked Bush if they could use it to connect further. Apartheid was a major consideration for Bush, who described himself as an “unrepentant hippy”.

“I had been raised to boycott all dealings with South Africa, as well as Franco’s Spain, Salazar’s Portugal and other international pariah states… Serious soul-searching led me to the conclusion that social change was not likely to be accomplished by cutting off communication. So I agreed on the condition that connectivity would be for universities and NGOs, and only those which were not apartheid-supporting or enforcing.”

Lawrie is convinced – although he concedes there is no way of really knowing – that being connected to the international community via e-mail helped bring apartheid to an end.

“I’m certain that the ability to e-mail the outside world had a bearing. I helped the guys to send Black Sash reports on the violence and killings in Uitenhage shortly after we connected to FidoNet. On the 21st of March, the anniversary of Sharpeville, there had been another police shooting. And those reports were hushed up. But we helped the Black Sash get them out via e-mail from Grahamstown.”

Breaking news in Rhodos

In the 23 March 1989 edition of Rhodos, the university’s in-house magazine, Lawrie broke the news that e-mail from Rhodes University had reached Portland, Oregon.

Under the headline: “E-mail: A major breakthrough”, Lawrie wrote:

The Rhodes computer network is now linked into the electronic mail networks of the academic world. This is a major expansion of a facility that has until now been limited to the universities in the PWV area (today, Gauteng).

Rhodes staff and students can now send and receive e-mail from universities and research institutions in the USA, Canada, Britain, Europe, the Middle East, Australasia, South America – virtually every major and minor e-mail network.

Lawrie goes on to note that after only three weeks of operation, “more than 100 messages per week are being interchanged on the international link. Much of this traffic is of a test nature at the moment, as people are establishing contacts and are learning how to use the system.”

A number of early e-mail adopters are quoted in the article, including Prof Trevor Letcher of the department of chemistry & biochemistry. He was on sabbatical at Carnegie Mellon University at the time, editing a journal.

He raved about “rapid informal communication between research workers in different institutions. It was so very good for me at Carnegie Mellon University to talk to colleagues 1 000km away, without postal delays or the high cost of telephone calls… It is perhaps the most revolutionary thing to have happened in scientific publishing over the past decade.”

Graham Oberem, then director of the computer-based education unit, was quoted as saying that “ideas can be exchanged with a turnaround time which is often less than 24 hours, results can be discussed and joint papers can be co-authored efficiently”.

Rhodes University staff went on to connect libraries, museums and other research facilities like the SA Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity.

The chicken and egg thing

Even so, e-mail was slow to take off.

As Jacot put it: “How do you tell people that e-mail will be useful if they’ve never had e-mail before? It was a solution in search of a problem. An egg before the chicken.”

Lawrie added: “Go back to that day when the first guy got a phone. How did he persuade his friend to get a telephone? Eventually I stopped trying to ‘sell’ e-mail. Don’t waste your time telling people something is good. They will see it. Just make it work. Reliably.”

Soon Rhodes was getting enquiries from universities wanting to exchange international e-mails.

“They said, ‘Can we?’ And we said, ‘No, you first need to satisfy the conditions so that Randy Bush will not go to jail under the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act.’ They had to make declarations, stamped, signed and whatever it is, and then e-mail started flowing from the other universities.”

In short order, Rhodes became the international e-mail gateway for universities and individuals in South Africa, swiftly followed by Botswana, Namibia, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Swaziland, Lesotho, Zambia and Ghana.

“FidoNet became the hub for all digital communication for Africa, and soon there was surprisingly heavy use,” said Dave Wilson.

Irate users

Prof Jonas added: “The simple twin-wire network that Mike set up became a victim of its own success. The demand for serial ports on the mainframe soon exceeded the available capacity of the machine. So a manual switchboard arrangement was implemented – just like telephone switchboards of old. You had to phone the operator in the computer room to ‘get’ a line, and he would plug the cable from your department into an available socket (if there was one available).

“There was no easy way to see if a connection was currently active, other than to unplug it and see if there was a reaction from an irate user who had lost their connection.

“Operators yanked the plugs out by their cables, often damaging the plug. So there would be protracted arguments over the phone, with the operator claiming that you were plugged in, but you were unable to connect.

“Mike once personally threw me out of the computer room when I stormed in with my multimeter and soldering iron to fix the broken plugs.”

Wily and innovative

Despite being under-resourced and in the constant onrush of new technology, Lawrie, Jacot, Wilson and telecommunications specialist John Stevens made it work. Stevens was their mainstay in dealing with Telkom, said Jacot, adding drily: “Without him, I would have killed several people.”

Pat Terry came up with some useful software.

“I wrote a program that would automatically intercept a fairly big message, split it up into smaller pieces, zip these to compress them before sending them separately down the line, where they would be uncompressed, and stitched back together again. As a result, you could send messages around that were longer than the small, one-page messages that FidoNet was best suited for. In the spirit of the amateur ‘Net, this system was soon in use on many other FidoNet nodes around the world.”

Even so, everything that could go wrong frequently did so.

“The worst part was a period of sheer pressure, trying to supply a reliable service with unreliable hardware and software that there wasn’t the time or the money to fix,” said Jacot. “You had to become wily and innovative about how you do things.”

Lawrie rates Jacot as one of the most incredible technicians he has ever met.

“Jacot made the computers work and kept them working. I would say: ‘Let’s see if we can talk to an IBM computer.’ You only had to give Jacot the slightest sniff of something like that and he’d be after it. Literally fantastic. He thrived on that sort of stuff.”

In 2011, Jacot wrote down some of his reminiscences of those time:

There were single critical points of failure, and boy did they fail! Equipment used to hang or run out of disk space all the time, and often it’d require two or three trips into the Rhodes computer room of an evening to reboot things and reset modems. Failures that took more than a few hours to resolve caused backlogs that took days to clear out. On more than one occasion, I’d hardly get home before there’d be another hang. This went on for about two years, but it seemed much longer.”

But solutions were eventually found.

Wilson added: “I worked with Brian Kemp and the Rhodes electronic services department to devise a circuit board that would monitor the transmit line from the PC. If there was no traffic on that line for 90 seconds, it would then conclude it was hung, and automatically send a reboot signal to the PC to get it going again. This worked flawlessly and kept the duration of outages to a minimum.”

Domain names

FidoNet proved to be extraordinarily resilient for a “toy system”. Pat Terry credits the people involved.

“FidoNet was amazing. The esprit de corps of the people using it, and their willingness to help one another, was just amazing. It was eye-opening. They got involved and solved each other’s problems. Because it was free, because it worked so effectively if you had a phone connection and a modem, and because there was this network of people to help, it spread around the world. It spread through Africa as well.”

By 1990, the computer team realised that in the long run, FidoNet’s “store and forward” message system was becoming unsustainable with the growing traffic. Instead, they had to look at “packet technology”, where e-mails find their own way instead of being “manually” sent from computer node to computer node.

Vinton “Vint” Cerf was called the father of the Internet for coming up with the Internet protocol that eased these packages through the ether, allowing them to arrive unchanged on the other side. He had devised TCP/IP to improve the functioning of Darpanet, later Arpanet, the first digital network in the world. Lawrie met Cerf at several international network conferences, and was “given every encouragement by him”.

But before live Internet connection, it was necessary to register domain names for the South African Internet, to give a space in which institutions and organisations could register unique names for their sites, and to produce viable e-mail addresses.

The .za part was already fixed, but what about the rest?

According to Jacot: “Mike, Dave and myself had a brief interaction with Randy Bush, who said, ‘Keep it short and simple.’ So, we arbitrarily decided, with no further consultation, on ‘ac.za’ for academic institutions, and ‘co.za’ for commercial organisations. This idea was quickly implemented, and Rhodes became the de facto ZA administrator until it was later outsourced.”

Finally, the ping

In late 1991, Telkom and an American communication company called Sprint worked together to connect a low-speed leased line between Rhodes University and Randy Bush.

John Stevens remembered that most of the communications happened at three in the mornings, which was working time in America.

One evening in late November 1991, everything was poised and ready. Stevens, Lawrie, Jacot and Wilson were on hand, waiting to send the Ping that would indicate everything was connected between Grahamstown (now Makhanda) and Portland, Oregon.

But nothing happened. No connection.

John Stevens said:

Eventually Sprint contacted us and said the pathway was stopping in Port Elizabeth (now Gqeberha). There seemed to be a disconnect there. So at three in the morning, I had to wake up the standby technician at Telkom and say: ‘We’ve got a problem, we need assistance.’ Not surprisingly, he was incredibly grumpy about being woken up and said as far as he knew the links to Grahamstown were in place and there should be no problem.

I said: ‘Listen, we’ve got Sprint online, we are all here, we’ve got to get this thing up and running, so you need to check what the story is. Louis du Preez very reluctantly went out to the Neil Street exchange in the middle of the night. Then he phoned me and said someone had pulled the links out. He plugged them back in, and the first ping went through.

Once it came alive, it was, ‘Wow, suddenly we are talking to the United States and the Internet. It was quite a feeling.’

At 10.44am next morning, 12 November 1991, Lawrie’s team sent their first e-mail to Randy using the TCP/IP line, and history was officially made.

Lawrie remembered: “I have no idea what it’s like to take drugs, but we were on a high for months and months.”

The elation was swiftly followed by a heady, stressful, roller-coaster year. An ever-growing volume of international Internet and e-mail traffic flowed into South Africa and most of its neighbouring countries via Rhodes University.

But eventually, the Eastern Cape’s telecommunications system could handle the ever-increasing traffic no longer, and South Africa’s primary digital gateway to the world was moved from Rhodes to Wits. In 1995, the South African Internet became commercial.

The make-do mavericks

No one at Rhodes University was paid for, or even set the task of making e-mails and the Internet function.

As Jacot explained: “This was all achieved with no formal budget. There was no money available to buy specialised networking hardware, so we had to make do using PCs that were considered old even by 1980s standards, ones that were no longer fit for purpose in a teaching or research context.”

Even so, opening the Internet gateway put the university into a different league.

Prof Pat Terry remembered: “It was an exciting time to be at Rhodes, when all this was happening. It was cutting edge and we were the acknowledged leaders in the country, with big cooperation from the University of Natal (Durban) and the people down at the University of Cape Town. The rest followed a bit behind. We retained the crown in that, for a while; people knew it was all happening at Rhodes.”

The Internet breakthrough had a direct effect on student numbers signing up for computer science, which was by then a fully fledged department, said Prof Terry.

“I can remember giving a talk at orientation week to all these new students and saying: ‘Computer science is a nice subject to do, you’ll be in reasonable-sized classes, about 30 in the class. You’ll get to know one another.’

“Come registration day, and blow me down if 120 don’t come to register. Where had they all come from? They streamed across the road in a long queue. And it carried on like that for the next few years.”

It made other things possible

Peter Clayton added: “It wasn’t long before we had lots of those early Internet companies, from around the world, coming through and recruiting. Microsoft, Netscape, later Amazon, those kinds of names.”

Jacot said: “The best part of all this, and what made it worthwhile both then and now, was being a small part of a large and willing community of very different people, all over the country and the world, who did complicated and stressful things again and again, not for any particular recognition or reward, but because it made other things possible.”

John Stevens did a tour of Ivy League Universities in the US in 2004. At that stage, Harvard University had a bandwidth of 3Gbit/s while Rhodes was purring along peacefully at a meagre 2Mbit/s.

“The Harvard people couldn’t believe it. How on earth could we cope with so little? The average household in America then had 2Mbit/s. We coped because Jacot and his team developed a system that allocated a usage quota of bandwidth to everyone. Each network user, from VC to first year student, had the same amount of allocated international bandwidth. We all had to share. We managed to do everything, with all our students and staff, on just two megs.

“Harvard thought it was brilliant.”

Stevens added: “Something else that was very vindicating for me, when I did the United States tour, was to see that Rhodes University was able to provide all the same services as the American universities, with a fraction of the resources.

“In the US, one guy does this, another does that. Here we had to take on all those roles. That’s the way things developed at Rhodes.”

Where are they now?

Now, after more than three decades, most people have forgotten that Rhodes University first brought the enormous gift of connection to South Africa. The pioneers on that first team are scattered far and wide.

Mike Lawrie left Rhodes to join UniNet in Pretoria in 1994. For a few years after he retired, he remained the sole arbiter of the .za domain. He set up and still runs the Internet service provider for the retirement village in Garsfontein, Pretoria, where he lives with his wife Christine and many succulent plants. His record of how e-mail and the Internet was founded in South Africa can be found at history.internet.org.za.

Dave Wilson took over from Lawrie as director in 1994, was elected to the board of UniNet-ZA, then left for America in 1999. He now lives in Massachusetts, working with a company that makes communication products for emergency services.

Jacot became director of Rhodes University computer services in 2002, and retired in 2014. He still lives in Makhanda and is busy growing a small forest of edible fig trees from cuttings.

Pat Terry continued teaching a few courses and setting notoriously diabolical examinations after he retired in 2010. He did the university timetable up until 2020.

Randy Bush still keeps in touch with his friends at Rhodes University. Back in Portland after a long stint in Japan, he has remained a key player in providing and administering the worldwide Internet.

John Stevens retired at the end of 2021. He considers it a great highlight of his career to have been part of the team that became a special part of South African Internet history.

Peter Clayton taught computer science at Rhodes after doing his PhD in the subject. He has just retired as the longest-serving deputy vice chancellor in the country.

Radio astronomer Prof Justin Jonas became the de facto architect of the MeerKAT radio telescope in the Karoo, a precursor to the international Square Kilometre Array (SKA). The equivalent of half of the world’s Internet traffic volume pours out of these telescopes, flowing in a never-ending torrent of data down glass fibres from the Karoo to Cape Town, then on to radio astronomers all over the world.

Jonas is still working on the top floor of the physics building, where Rhodes University computing all began.

- A longer version of this article first appeared in Rhodes University Research Report 2021, published in November 2022

- This version of the article, first published by Karoo Space, is republished with the kind permission of Rhodes University

- Photographs in this article are by Chris Marais, or are supplied

- The author of this article, Julienne du Toit, is the co-author of the Karoo Roads trilogy, available for R800 including courier. E-mail [email protected] for more information