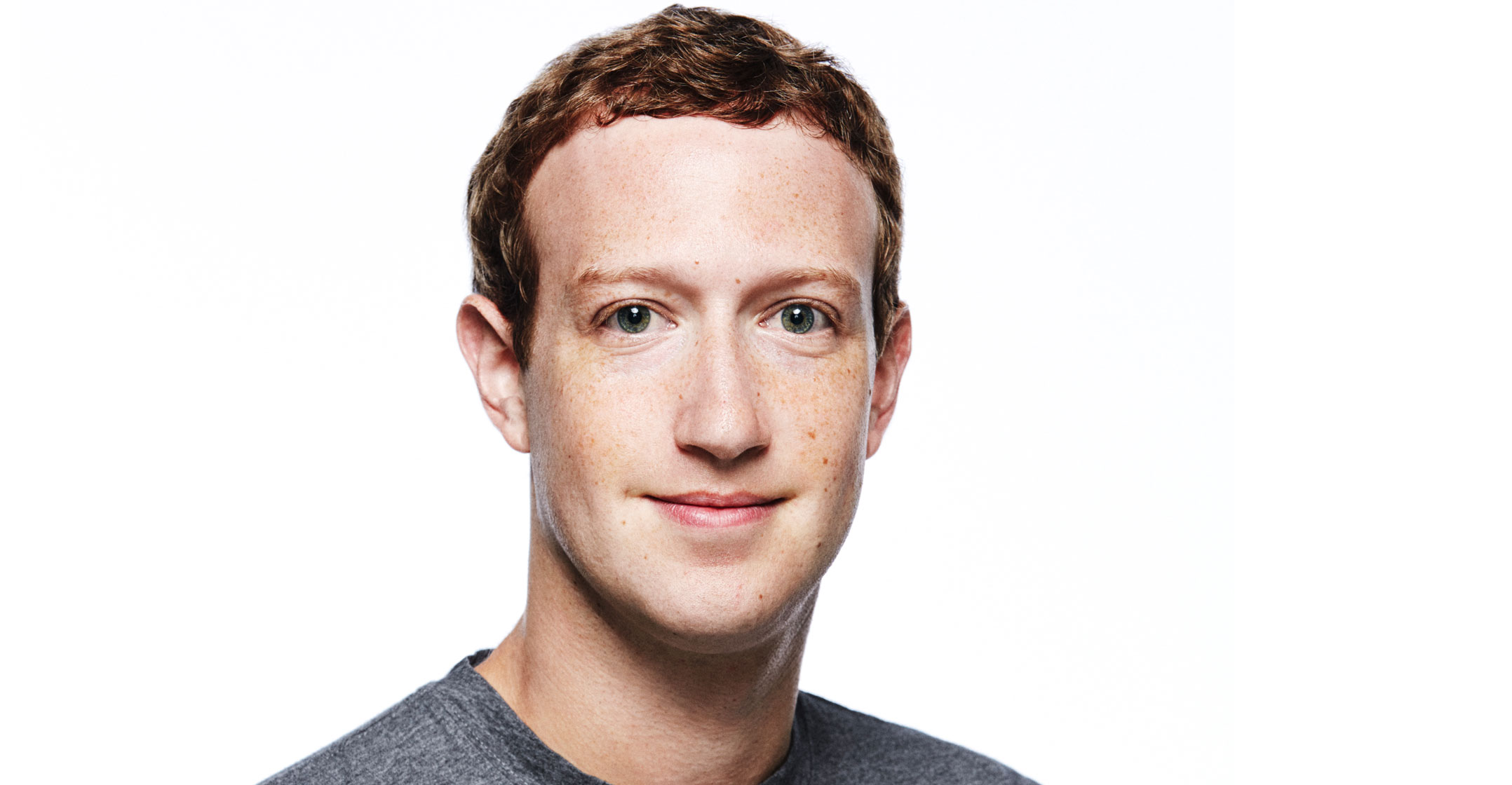

First, a confession: I’m getting bored with Mark Zuckerberg’s manifestos.

As the public spotlight on Facebook has illuminated the company’s many ugly corners, Zuckerberg has put pen to paper multiple times to declare mission statements for his company. On Wednesday, the CEO declared that the future of Facebook is … well, it’s more like Snapchat. He said Facebook would emphasise communications among smaller groups, temporary posts and technology that keeps outsiders and Facebook itself from peering into what people are sending through its social network and company-owned Instagram, WhatsApp and Messenger apps.

Zuckerberg has been talking for some time about what he says are people’s growing preferences for more intimate online interactions rather than the public, permanent broadcasts that made Facebook one of the most widely used digital tools in history. His 3 200 words on Wednesday were more urgent and thoughtful than what he’s said before, and Facebook made sure that his post sparked conversation about the company’s new, privacy-focused direction.

The trouble is, I’m not sure whether Facebook is truly changing its stripes. I give Zuckerberg credit for recognising — although maybe two to five years too late — that there are downsides to a medium that’s intended to connect the world, and by nature tends to spread the most provocative and outlandish voices far and wide. But let’s press pause on reading too much into Zuckerberg’s mission statement until we see how Facebook changes, if at all. A call to arms from the CEO can spark real change, or it might just be words.

It’s not clear how Zuckerberg’s statement will change how the company functions, or whether the company will end up collecting more or less personal data that fuels its advertising system. There are also potential downsides to making Facebook less public, including limiting the company’s responsibility to police its digital hangouts for hate speech, attempted social manipulation or other abuses.

Context is key

The context is key here. Facebook right now is working on a complex project that aims to combine the technology foundations of Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp and Messenger. One goal of this project, as Zuckerberg wrote in his post, is to permit someone using Instagram, for example, to send a digital message to someone using WhatsApp.

If I strain my mind, I can imagine some circumstances where this would be useful. What Zuckerberg didn’t mention is what this long-term “interoperability” project will do for what I think is the original sin behind every Facebook scandal: its hoarding of data on just about every Internet user.

If the company shifts to a common foundation for its apps, in theory that could give Facebook an even larger and cleaner database of people’s online and real-world behaviour with which to target advertising. It’s also possible that Facebook’s move to combine its Internet hangouts, and make them encrypted so the information moving among them is scrambled, may limit the data Facebook collects. Zuckerberg doesn’t really address either possibility.

I can’t help thinking that Zuckerberg’s high-minded talk about more private and scrambled communications through Facebook and its other apps is simply putting a shiny gloss on what is otherwise a power play by Facebook to consolidate power and data about Internet users by merging its multiple services.

I can’t help thinking that Zuckerberg’s high-minded talk about more private and scrambled communications through Facebook and its other apps is simply putting a shiny gloss on what is otherwise a power play by Facebook to consolidate power and data about Internet users by merging its multiple services.

Scrambling communications, or encryption, also means it will be difficult or impossible for Facebook to comply with the growing, admittedly thorny, demands on the company to screen and remove posts advocating violence, illegal activity, hoaxes and other scum that collects in its pipelines. Facebook can throw up his hands and say that encryption prevents it from tracking those Russian-backed networks trying to manipulate an election. It also means people can use Facebook to organise against a coercive government with less fear of being discovered. Removing Facebook or outside prying eyes from peering into the digital traffic is a trade-off, and Zuckerberg does acknowledge this.

Zuckerberg’s post talks about making Facebook and its Internet hangouts more of an intimate digital “living room” rather than a raucous public town square. It’s a lovely metaphor. But I’m less curious about whether and how Facebook will shift the behaviour of people online, and more about the remodelling the company does to itself to limit its privileged position in two billion virtual homes worldwide. — (c) 2019 Bloomberg LP