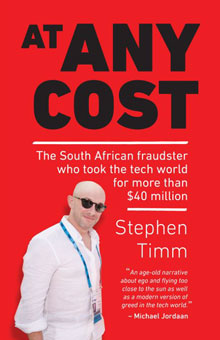

In this extract from At Any Cost, a book on convicted South African fraudster Elan Eyal, author Stephen Timm – a technology journalist and former editor of VentureBurn – explains how technology entrepreneurs like Eyal are able to hoodwink angel investors into parting with their money, even when there is little of substance behind their ideas.

The book, published by Tafelberg, unpacks how Eyal – who relocated from Cape Town to New York to pursue his ambition of making it big – “took the tech world for more than US$40-million”.

As Timm explains in the book, US authorities pounced in Eyal in 2018, charging him with fraud. “There began the gobsmacking unravelling of a scam that spanned investors across the globe and revealed that Eyal had built a house of cards involving fictitious products, clients and advisors for Shopin and his previous company, Springleap.

“As more than $40-million went up in smoke, the South African entrepreneur was exposed as an audacious fraudster determined to succeed at any cost – even if it meant spinning a web of lies to do so.”

After his conviction, many of Eran Eyal’s victims — and those who knew him (or thought they knew him) — asked: Why did he do it?

It’s the one question that keeps coming up. Was he just like any other tech entrepreneur, who is driven by dreams of making it big, and who ends up talking up their company a little too much? Or was there more to it?

I began to wonder if, what really drove Eyal, was competition with Avi — to get the attention and respect that he always felt had eluded him. He had lived in the shadow of his wildly successful brother for many years. Had Eyal decided that if he couldn’t make a success of himself as an honest person, he would resort to anything to win?

Another question to ponder is why so many investors had fallen for Eyal.

One investor, investment banker Jeremy Katzen, put US$20 000 in Springleap in about 2014. He even asked Eyal a number of times why he hadn’t got Avi to invest in Springleap. Eyal’s response was always the same – that Avi didn’t want to mix family with business. “I always wondered if he was living in Avi’s shadow,” Katzen recalls now. Yet Katzen spent his working life analysing companies in which his firm could invest. How had he not spotted that Eyal had inflated everything about Springleap?

Talking today, Katzen admits that he hadn’t conducted any due diligence on the deal because his friend, Tim Leclercq, had already committed to investing in Springleap. Katzen’s experience was a classic example of the way many private individuals or angel investors get hoodwinked. Many don’t bother to do background checks.

Who else invested?

They don’t speak to staff or sit in on meetings or drop in unexpectedly at a start-up’s offices. The choice to invest is more often based on who else has already invested, than on anything else. Rope in a few big names and make a big fuss about it to others and reeling in more investors becomes easy.

The secretiveness in the tech start-up sector also makes it easy to get away with projecting your company as something it’s not. And no one is checking up on you. Entrepreneurs can easily hide behind technical language that makes the business sound like the next biggest sensation. All the better if the entrepreneur is able to craft an excellent pitch deck and press release to amplify this. Perception is everything.

Blogs and other small Web publications make up most of the media that cover the start-up sector. Most of the journalists who report on the sector seldom ask critical questions, either out of a sense of complacency or because the sector is dominated by PR firms that help start-ups to craft their public image through well-worded releases and images that overhype their service or offering.

Everyone is expected to join in on the excitement that is generated when another start-up lands investment. Those in the tech sector – other entrepreneurs and investors – are often so busy slapping one another on the back and fist-pumping each other when a deal lands that they often neglect to look further at such details, as to who the firm’s clients are, how many clients the company really has, or whether the technology actually works.

Everyone is expected to join in on the excitement that is generated when another start-up lands investment. Those in the tech sector – other entrepreneurs and investors – are often so busy slapping one another on the back and fist-pumping each other when a deal lands that they often neglect to look further at such details, as to who the firm’s clients are, how many clients the company really has, or whether the technology actually works.

Johannesburg venture capitalist Clive Butkow puts it down to angel investors not spending enough time with the founder and their team to gain an understanding of their culture. “Many entrepreneurs you meet are very charismatic and talk their way out of any situation. You have to ensure your bullshit meter is working and you can discern the sales fluff from the truth,” he says. He points out that investors often make decisions with their gut rather than on the basis of confirmed data. This isn’t so good when, in many instances, the entrepreneurs create a sense of urgency to ensure that investors make a rash decision without conducting a full due diligence study of the potential investment. “They have fear of missing out through the entrepreneur putting them under pressure to make quick decisions rather than right decisions,” says Butkow.

Angels

Importantly, Eyal turned to angel investors rather than institutional investors such as venture capital companies when looking for investment. “Angels are generally more on the Dragons’ Den lust-for-blood side of things, saying ‘Gosh I’ve got some money and I’ve got the network’,” points out veteran South African venture capitalist Keet van Zyl. “It’s people who are investing in gut feel more than anything else,” he says. Had Eyal tried to get venture capital for Springleap, Van Zyl reckons he would not have been successful. “A lawyer would have gone into the intellectual property and reference calls would have been made,” he says.

Another local veteran venture capitalist, Brett Commaille, says many investors are led astray by tech entrepreneurs who are ardent followers of the fake-it-till-you-make-it approach. “It’s based on someone who went to sell their new product and the customer said, ‘Okay, but can you do X and Y?’ ‘Absolutely!’ came the response.

Entrepreneur rushes back to team and they build the solution. Customer pays and is mostly happy. Great story. Sadly, there are far too many who lie about the ability or capability, and never deliver on the product. even then we get it wrong.”

- At Any Cost is available in good bookstores