Even in a year when bashing tech companies has become a bipartisan avocation, last week’s US antitrust assault on Facebook stands out. The social media giant now faces dual lawsuits from the Federal Trade Commission and 46 state attorneys-general seeking, among other things, to undo forcibly its acquisitions of Instagram and WhatsApp.

Even in a year when bashing tech companies has become a bipartisan avocation, last week’s US antitrust assault on Facebook stands out. The social media giant now faces dual lawsuits from the Federal Trade Commission and 46 state attorneys-general seeking, among other things, to undo forcibly its acquisitions of Instagram and WhatsApp.

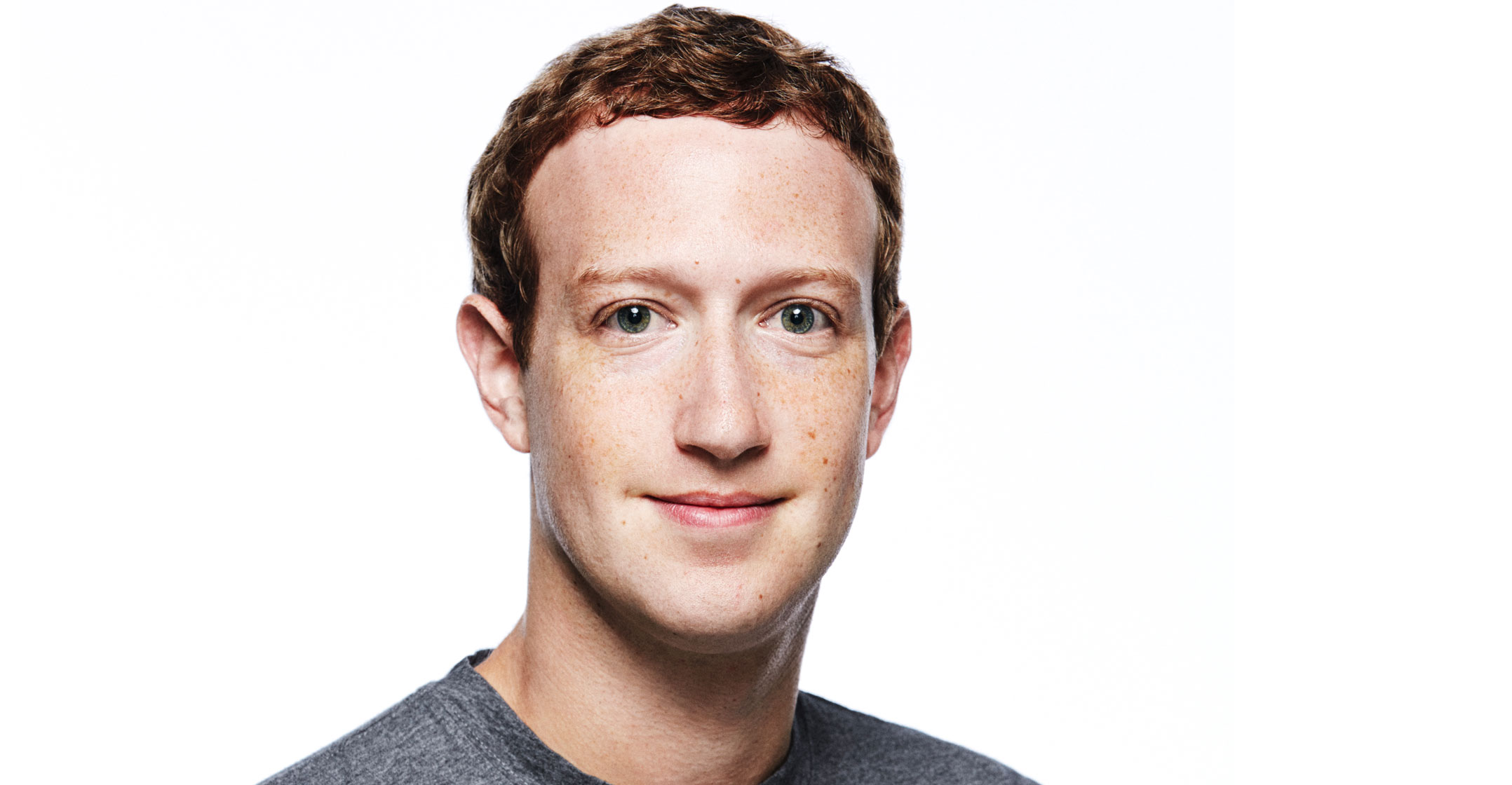

Given this alliance of federal regulators and so many states, red and blue, you might think the case is open and shut. And sure enough, Facebook being Facebook, the complaints are packed with internal e-mails boasting about dubious objectives and unseemly motivations. (“It is better to buy than compete,” Mark Zuckerberg writes at one point.) Look closer at the underlying conduct, though, and the suits are far weaker than they seem.

To be clear, the wisdom of allowing Facebook to buy Instagram in 2012 and WhatsApp in 2014 is up for debate. Although few people at the time thought either company was a direct threat to Facebook’s core business, their combined firepower in the hands of an already dominant platform was certainly enough to give pause. One can imagine — as these lawsuits do — a world where both services developed in more productive or desirable directions.

But the fact is that the FTC itself scrutinised and approved both mergers, and if all those attorneys-general objected at the time, they kept it to themselves. The courts will decide if reversing course nearly a decade later and demanding a breakup correctly applies the law. But it looks like a hard case to make. Facebook, having received the government’s go-ahead, spent billions of dollars integrating both services — including systems for advertising, commerce, messaging, cybersecurity and more — into its ecosystem. It’s not clear how a breakup would even work at this point, let alone how it could remedy the many harms alleged in these suits.

Changed utterly

More to the point, the competitive landscape has changed utterly. Dozens of new entrants now fight with Facebook for attention and ad dollars. The FTC imagines that both Instagram (a photo-sharing app) and WhatsApp (a messaging service) might’ve matured into innovative and profitable social media platforms in their own right. Yet it also insists that Facebook faces no serious competition from the likes of Snap and Slack, YouTube and LinkedIn, Reddit and Discord — any of which, by the FTC’s own logic, could surely do the same.

Gliding by all this, both suits simply assert that Facebook is an unlawful monopoly. By any conventional metric, though, it isn’t. Facebook charges nothing for its services, which hardly suggests harm to the consumer. Online ad rates have fallen by nearly 40% since 2010, which doesn’t exactly look like an uncompetitive market. As for barriers to entry, look no further than TikTok, which was launched only four years ago and now has some 800 million users. Even if Facebook’s goal was to squash competition — as some of the cited e-mails suggest — the effort has plainly failed. (“Facebook has used its monopoly power to crush smaller rivals and snuff out competition,” writes New York attorney-general Letitia James on Twitter, yet another competitor that hasn’t been snuffed out.)

The lawsuits are on firmer ground in alleging that the company’s rules for third-party apps using its platform were anticompetitive. As a condition for accessing its APIs (the interfaces that allow the apps to send or receive data) it prevented them from offering competing services or promoting other social networks. That does call for remedies — but it hardly justifies breaking up an US$800-billion company with 45 000 employees.

Antitrust enforcement has to be used judiciously, and with clear purpose. Better remedies are often available. If the US congress objects to Facebook’s treatment of user data, it should pass a national privacy law. If it thinks mergers in the tech business deserve closer scrutiny, it should give the FTC and the department of justice more resources for that purpose. Launching a retrospective review of acquisitions the government has already approved — while demanding hugely disruptive remedies, with no clear aim in sight — is almost certain to backfire. Better to get it right the first time. — (c) 2020 Bloomberg LP