It is obvious that electricity disruptions are bad for business and the economy. Smaller businesses can counter the effects of load shedding for a few hours by using standby generators — at a cost — but large enterprises simply cannot operate without steady and adequate power.

It is obvious that electricity disruptions are bad for business and the economy. Smaller businesses can counter the effects of load shedding for a few hours by using standby generators — at a cost — but large enterprises simply cannot operate without steady and adequate power.

In fact, the South African Reserve Bank (Sarb) noted in its latest quarterly bulletin that the prime reason for the recovery in economic activity in the second quarter of 2019 was the absence of severe electricity disruptions that hampered output in the first quarter. “Real GDP advanced at an annualised rate of 3.1% in the second quarter, after contracting by a similar magnitude in the previous quarter,” say the bank’s economists in their review.

The ongoing problems at Eskom have had such a huge effect on the economy that it urged the Reserve Bank to look into it closely, with an analysis showing that electricity disruptions during the three months to end March were the worst ever, barring the second quarter of 2015.

The measure is based on the number of days of electricity disruptions in each quarter and the level of load shedding, with a higher stage of load shedding given a higher weighting to quantify the intensity of electricity disruptions.

For example, three days of stage-1 load shedding equal an intensity of 3, while three days of stage-2 load shedding equal an intensity of 6. In the first quarter of 2008, the calculation yielded a figure of 34 when South Africa had three days of stage-1 load shedding, three days of stage 2, seven days of stage 3 and one day of stage 4.

Sarb rated load shedding in the first quarter of 2019 at an intensity of 41, due to five days of stage-4 load shedding.

Tongue-lashing

The result was that the economy shrank by 3.1% in the first quarter and recovered by 3.1% in the second quarter after Eskom received a tongue-lashing from the president’s office and got its act together.

Economic growth in the second quarter of 2015 was a negative 1.3% as measured by the real GDP, but it’s noteworthy that load shedding did not reach stage 4 then.

The analysis of the effect of load shedding in the Quarterly Bulletin clearly states that there are lots of factors that can impact economic activity, besides the shortage of electricity. Sarb points out that the economy suffered in certain quarters when there was no load shedding as well.

It listed the various other factors that probably impacted economic growth, such as a number of long labour strikes, maintenance and safety stoppages in the mining sector and weak domestic and and global demand, as well as political and policy uncertainty, which affected business and consumer confidence.

However, there seems to be an uncanny correlation between load shedding and a declining economy. The economy posted negative growth in all the quarters in which load shedding occurred — except for the first quarter in 2008 when load shedding was actually quite severe.

However, there seems to be an uncanny correlation between load shedding and a declining economy. The economy posted negative growth in all the quarters in which load shedding occurred — except for the first quarter in 2008 when load shedding was actually quite severe.

Paging through a few older economic reports shows that power failures were blamed for the lacklustre performance of the mining and manufacturing industries in every quarter characterised by electricity shortages.

Sarb notes in its analysis of the effect of electricity shortages on the economy that the electricity-intensive mining and manufacturing sectors have often been affected the most, with agricultural and transport sectors also affected.

All the South African mining companies blamed disruptions in electricity supply for their bad results in the first quarter of 2019 and attributed the strong recovery in production levels in the second quarter to a steady supply of electricity.

Sarb noted that the real gross value added (GVA) by the primary and secondary sector sector increased notably in the second quarter of 2019, following several quarters of contraction. “The marked turnaround in mining output was fairly broad based and contributed the most to overall real GDP growth in the second quarter.

“Following a sharp contraction in the first quarter of 2019, the real output of the secondary sector increased moderately in the second quarter as continuous electricity supply was restored, supported by unit 3 of Eskom’s Medupi power station becoming operational. The real GVA by the manufacturing sector as well as the sector supplying electricity, gas and water reverted from sharp contractions to expansions,” says the bulletin.

Regression model

The intensity of load shedding and analysis notes that the impact of load shedding on real GDP was also tested by using a regression model, basically to see if the calculations are of statistical importance.

The results show that as the intensity of load shedding increases, the decrease in SA’s real GDP growth is statistically significant by 0.06%.

The real GVA of all the economic sub-sectors displayed a (negative) correlation to the intensity of load shedding.

In short, the report proves what everybody already knows: businesses cannot operate without electricity and without operating businesses the economy cannot grow.

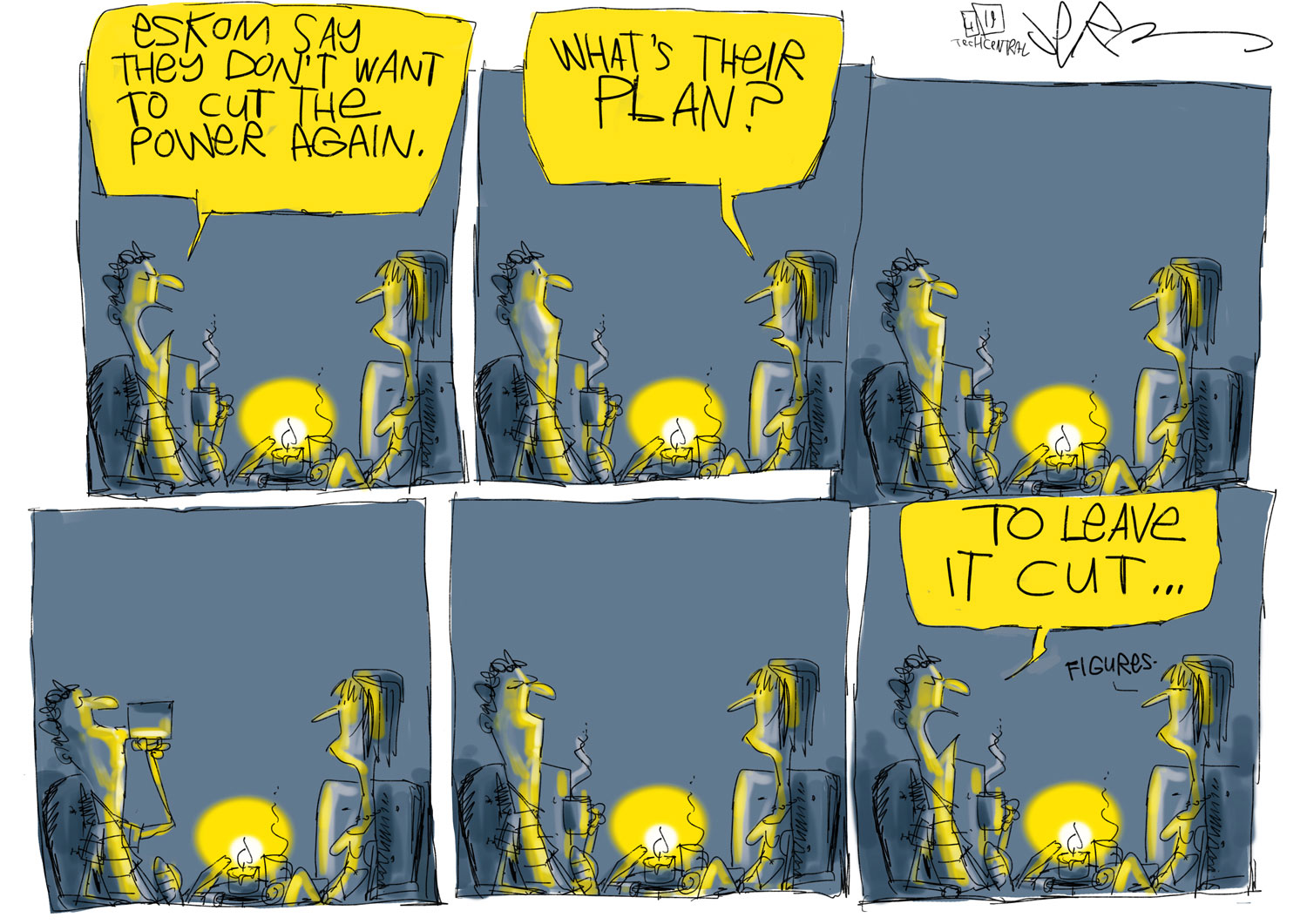

Solving Eskom’s problems will solve a lot of other problems. Hopefully the managers at Eskom will read the report, too.

- This article was originally published on Moneyweb and is used here with permission