There is abundant evidence that poorer people in Africa are now using the Internet. In South Africa, most new users come from low-income households, many of them living below the poverty line.

There is abundant evidence that poorer people in Africa are now using the Internet. In South Africa, most new users come from low-income households, many of them living below the poverty line.

The main driver of this trend is declining costs. Most people in Africa connect to the Internet via mobile devices and the price of these is falling. Nokia, for example, launched a US$29 Internet phone this year.

Pay-as-you-go data can be purchased in small bundles in many African countries, sometimes in increments as low as $0,10. This is true even though data prices in South Africa remain high.

Solid data on how far Internet use has spread is limited. The most reliable survey conducted in 11 countries in 2011 and 2012 found that about one in three South Africans, one in four Kenyans and fewer than one in 20 Ethiopians used the Internet.

But it appears clear that where networks are available and prices are affordable, people will use Internet services.

Low-income users appear increasingly aware of the benefits of Internet access. A study just published of South African users on low and very low incomes (most of them in households with incomes between about $45 and $450/month) found that many were aware of and used sophisticated online tools.

They recognise the power of the Internet for improving their lives, in looking for a job for example.

The Internet implies a single thing, a single network. But we may be coming to a point where this is no longer a useful way to describe the realities of the complex web of physical, economic, social and content networks that span the planet.

For those who are well connected, some in Africa, but most in rich countries, the Internet means a wide range of services — from quickly messaging friends to storing files and photos in the cloud to accessing global databases. All are available quickly and cheaply 24/7 at home, at workplaces and educational institutions and in public spaces on a variety of devices including those with keyboards.

For many of Africa’s new users, the Internet means access to instant messaging (a cheaper substitute to expensive SMS) and some social media via a mobile phone. It is highly rationed and slow.

Our research shows that rich media online — music and video — is consumed very lightly because of cost and slow connections.

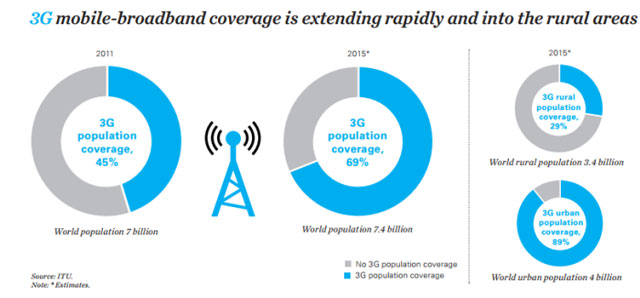

Broadband challenges remain

This research, and the work of others, point to the fact that for the poor, in Africa and elsewhere, the Internet is a mobile-centric world.

So people on low incomes are getting benefit from Internet access. But the experience is a long way from the visions of broadband for all which more than 20 African countries have committed to.

As one young Internet user told me in a village in Kenya, you can’t write a job application on your mobile phone. And dependency on mobile networks also means that where competition is limited, data costs are too high for many people to consume data on anything but a very rationed diet.

There are also concerns about the openness and security of the Internet in Africa. There are significant threats of censorship. Some initiatives to make the Internet more widely available are being challenged, undermining its openness.

The next meeting of the World Internet Project, a network of researchers from over 30 countries, is to held in Africa for the first time. The July gathering in Johannesburg will be an opportunity to compare progress and challenges on the continent with other parts of the world.

It will also provide the opportunity to engage with policy makers, researchers and the private sector on how to build on what has been achieved to enable an affordable, accessible and open Internet that is truly global.![]()

- Indra de Lanerolle is visiting researcher, Network Society Project, at the University of the Witwatersrand

- This article was originally published on The Conversation