Nine months after a scandal erupted over Facebook’s open borders of user information, those borders are in the news again.

The New York Times reported late on Tuesday that after Facebook tightened rules in 2015 to limit the account information that could be hooked into outside companies’ apps and websites, the social network made many exceptions and some previously made special deals continued until recently.

Those arrangements allowed companies such as Apple, Amazon, Microsoft and Netflix to have a sometimes unsettling level of access to Facebook users’ information. The Facebook data pipeline included, the Times said, Netflix and Spotify being able to read people’s private Facebook messages and letting Amazon obtain Facebook users’ names and contact information through their online friends.

Facebook’s explanation is that the flow of information between its user repositories and the company’s partners did require the consent of Facebook account holders, and that agreements with more than 150 companies such as Microsoft, Yahoo and Apple obliged those partners to comply with Facebook privacy requirements and weren’t abused.

Many of the third-party data agreements described in the Times article appeared to have been relatively unused or dormant, and the news organization didn’t identify examples of Facebook’s partners siphoning mass amounts of information about Facebook users or otherwise abusing their access. That’s good, but it doesn’t absolve Facebook of blame here.

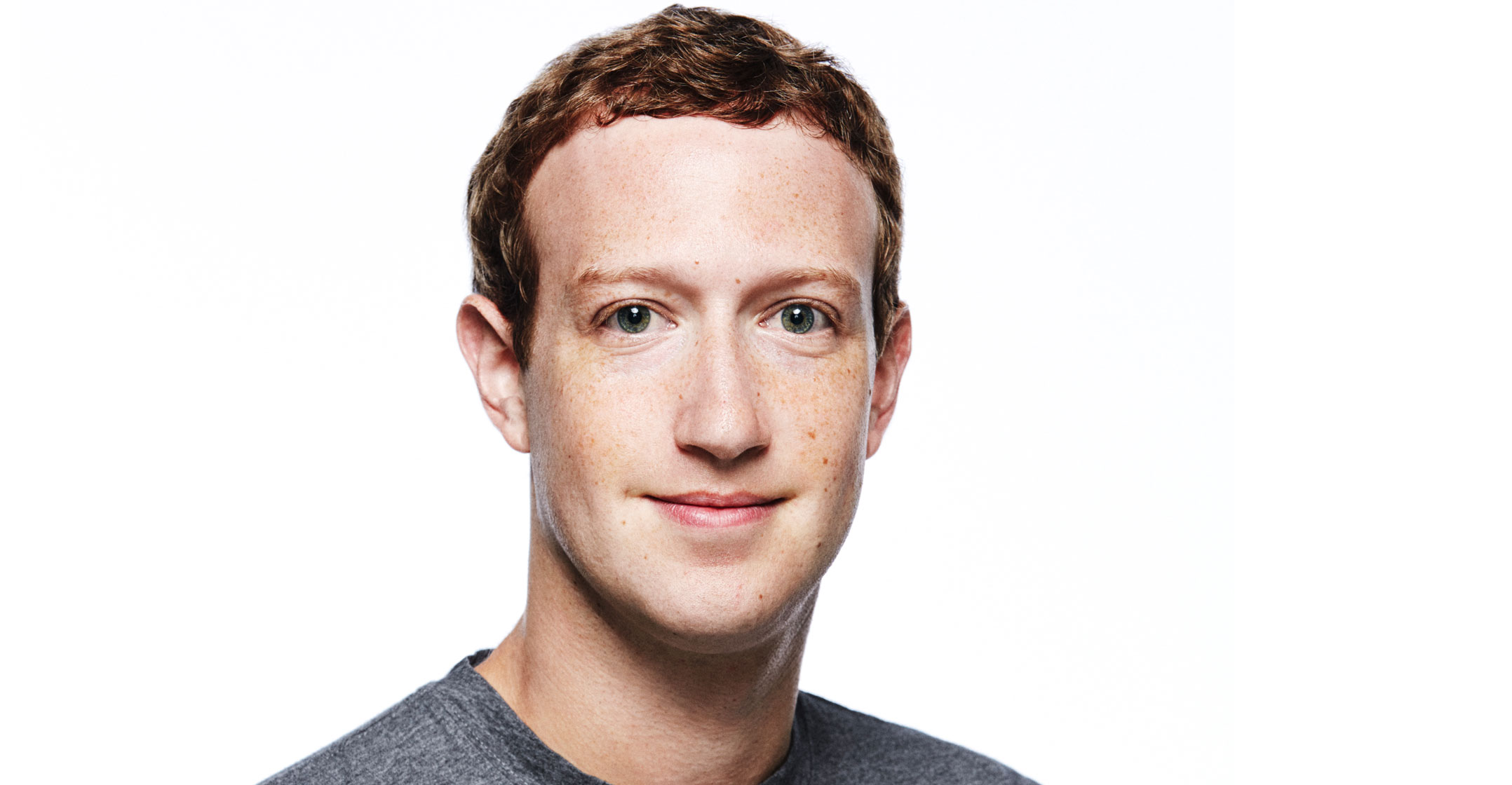

CEO Mark Zuckerberg has a mantra that he told members of the US congress and has repeated frequently: people who use Facebook have control over how their information is used. That is true in only the strictest sense.

Eyes wide open

Consent — which might mean someone entered her Facebook password once in 2013 — in the Internet world does not match how normal humans think about permission. I’ve written before that the open data sharing that made the Internet useful — for example, by knitting together your Gmail account with an online file storage service so you can e-mail a document to a colleague — helped make our lives easier but also let our digital information loose in a way that most people didn’t understand, let alone agree to with eyes wide open.

My bigger issue with Facebook is it has missed repeated opportunities to come clean about the scope and breadth of its information pipelines with outside companies.

After the March revelations about how Cambridge Analytica appeared to take advantage of loose Facebook rules to gather information on people’s Facebook friends without their overt approval, we were somewhat comforted by the idea that this was a vestige of Facebook past. Facebook changed policies after 2014, and there would never be a repeat of this Wild West with Facebook user information.

Since then, though, there have been dribs and drabs of reporting from news outlets that even after Facebook tightened its rules about the account information outside companies could harness, Facebook made many exceptions or let old agreements continue long after they stopped being useful. Maybe those special deals were fine to make, met the smell test of consent from Facebook users, and complied with Facebook’s 2011 agreement with the US government to never again share user information without people’s explicit permission. Maybe.

Since then, though, there have been dribs and drabs of reporting from news outlets that even after Facebook tightened its rules about the account information outside companies could harness, Facebook made many exceptions or let old agreements continue long after they stopped being useful. Maybe those special deals were fine to make, met the smell test of consent from Facebook users, and complied with Facebook’s 2011 agreement with the US government to never again share user information without people’s explicit permission. Maybe.

Even if all that were true, why didn’t Facebook do a full accounting after March of all its partnership arrangements that hooked outside companies into Facebook data? That’s my real complaint here. Facebook cannot seem to clean up its own mess.

After the Cambridge Analytica revelations, Facebook should have peered into all the dusty corners of its closet and dragged out all of the skeletons. It had an opening to detail all the companies that had special arrangements for account information for purposes such as recommending Netflix movies that I liked to my contacts on Facebook Messenger. There’s no evidence that Netflix used its ability to peek into people’s private messages, but it sounds creepy, and Facebook whiffed on its chance to identify any open data pipelines, plug up the ones that weren’t absolutely necessary, and make a full accounting to the public and the US congress.

At their root, disclosures about Facebook’s data deals undermine trust in the company. The company that says it is committed to transparency repeatedly fails to be transparent. A company that says safeguarding the privacy of its users is its paramount mission has repeatedly failed to truly safeguard their privacy. And the company that says it has learnt from its mistakes keeps missing chances to reform its bad old habits. — Reported by Shira Ovide, (c) 2018 Bloomberg LP