Long before Broadcom sealed a deal to buy VMware for US$61-billion on Thursday, it eyed the company secretly from a distance.

VMware had been one of the assets at the top of Broadcom’s target list for some time, according to people familiar with the matter, but the suitor quietly scrutinised the business before it went further. Broadcom crunched numbers, scoped out VMware’s products and ran scenarios for about a year before making an approach, said the people, who asked not to identified because the deliberations were private.

Thus began what is set to be the biggest takeover by a chip maker in history and one of the top tech deals of all time. Thursday’s agreement marries a sprawling semiconductor company with a Silicon Valley software pioneer — a merger few had anticipated before Bloomberg broke news of the talks earlier this week. Broadcom plans to make VMware the linchpin of its software strategy, reducing its reliance on the boom-and-bust chip industry.

The courtship started slowly for good reason. VMware was part of Dell Technologies until a spinoff last year. That split, announced in April 2021 and completed on 1 November, extricated VMware from Dell and made it more attractive as an acquisition. But Broadcom executives couldn’t act on anything or show their interest until at least six months after the deal closed, the people said.

Tax rules prevent a spun-off company from having M&A conversations for a period of time — lawyers generally advise a six-month window — so Broadcom had to wait until it felt VMware would be willing to engage.

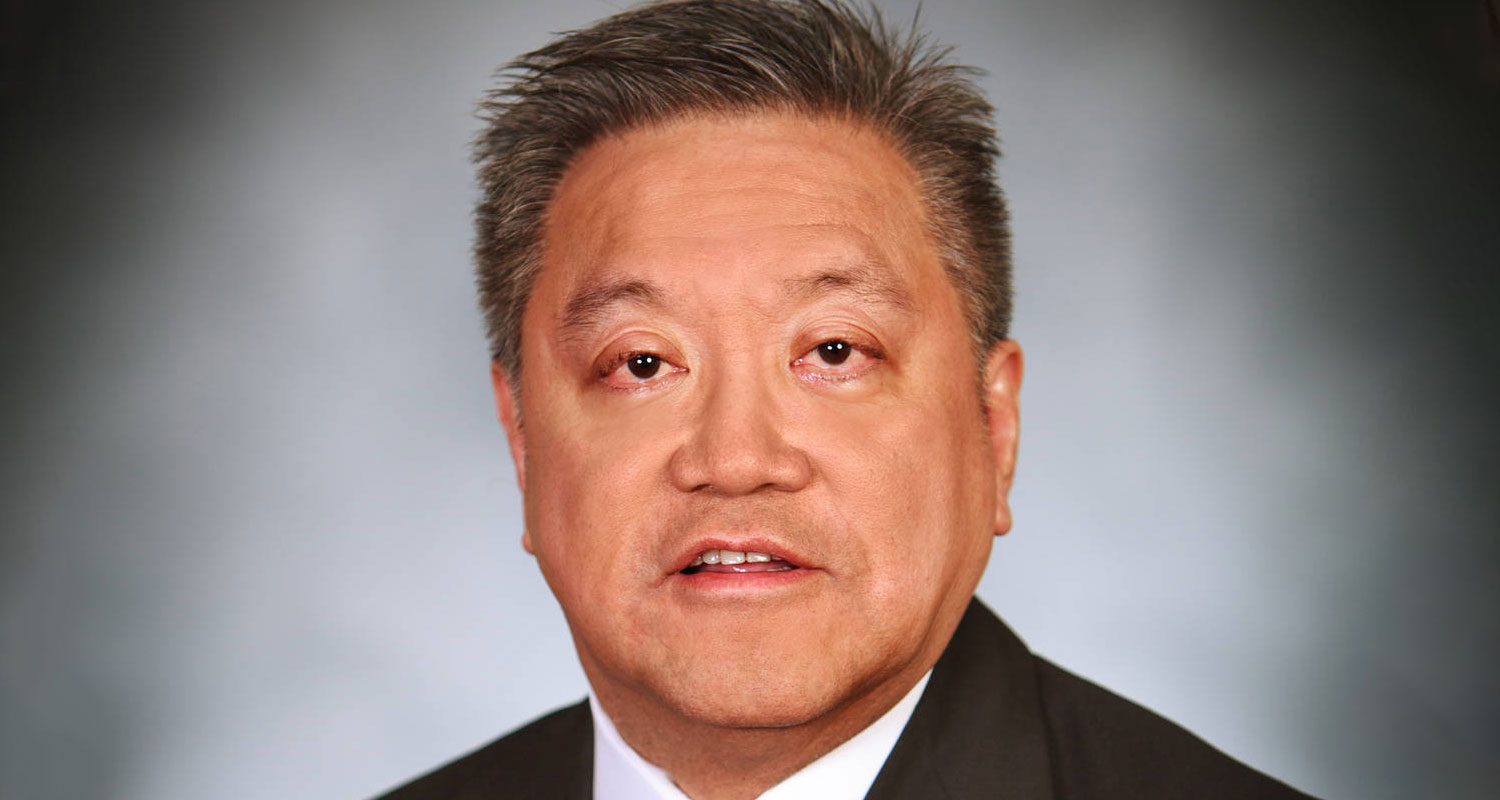

The talks got going in early May with a phone call from Broadcom CEO Hock Tan to Michael Dell, who had remained the top shareholder in VMware after the spinoff from his computer business. Tan, a Malaysian-born entrepreneur who built Broadcom into one of the biggest and most diversified chip makers, wanted to sound out Dell about interest in a tie-up.

Receptive

The two men set up a meeting in Austin, Texas. There, Tan made his official pitch: he promised to offer a generous premium and deliver value well above that. Dell seemed receptive to the idea, in part because VMware’s stock — of which he owned 40% — hadn’t been performing well since the spinoff. VMware’s board, where Dell is chairman, formed a transaction committee to analyse a possible takeover.

But if the deal had a slow start, the two sides soon made up for lost time. Once they both agreed to move forward, the transaction came together in about two to three weeks.

In addition to Tan and Dell, the chief negotiators were Broadcom software head Tom Krause and Egon Durban, a partner in private equity giant Silver Lake. The investment firm is a major VMware shareholder and had helped Dell’s namesake company go private nearly a decade ago. VMware was advised by bankers at Goldman Sachs Group and JPMorgan Chase & Co.

Broadcom is no stranger to M&A. The company was the product of a 2016 merger with Tan’s Avago Technologies, and it has completed several blockbuster deals since then. Broadcom sped through the process.

“We pride ourselves on having a very clear vision in terms of what we want to do,” Broadcom’s Krause said in an interview. “And when we see these opportunities, we move quickly.”

Advisers were retained, and staff hustled to complete diligence to bring together VMware — code-named Verona during the talks — with Broadcom, which went by Barcelona.

The European theme was fitting because Dell was in Davos, Switzerland, during the final leg of talks. Broadcom, meanwhile, worked with at least four banks, and then brought in two more during the days leading up to the deal.

Those six firms — Barclays, Bank of America, Citigroup, Credit Suisse Group, Morgan Stanley and Wells Fargo & Co — ended up agreeing to lend Broadcom $32-billion, the largest debt financing in more than a year.

Despite the market turmoil punishing tech stocks this month, the deal proceeded smoothly and with regular due diligence. People close to the talks said it was more of a traditional negotiation than they saw with the last big tech deal this year, Elon Musk’s $44-billion takeover of Twitter.

The two sides wanted to move fast — to minimise leaks and cope with a volatile market — so VMware held off on speaking to other potential bidders, according to the people with knowledge of the discussions. Instead, a so-called go-shop clause was included in the agreement.

It is what it is. It’s part of a highly negotiated deal. There were a lot of trade-offs made

Under that provision, VMware will be able to solicit competing offers for the next 40 days, which is rare in strategic deals of this size. That gave VMware’s board the comfort that it could proceed.

Both sides agreed to a $1.5-billion breakup fee, but VMware only has to pay $750-million if it can find a superior offer by the 5 July deadline. Having the go-shop provision in the agreement made the deal more palatable to VMware — and Broadcom was willing to live with it.

“It is what it is,” Krause said. “It’s part of a highly negotiated deal. There were a lot of trade-offs made.”

Based on the price and other conditions, he said, “putting in the go-shop — that seemed like the right balance”. — Liana Baker and Michelle F Davis, (c) 2022 Bloomberg LP