“It costs more to get data to the coast than it does to get it the rest of the way to Europe.”

“It costs more to get data to the coast than it does to get it the rest of the way to Europe.”

Since the arrival of high-capacity undersea fibre-optic cables to African shores in 2009, I have heard this complaint repeated across countries in sub-Saharan Africa and still do. Seven years later, there is now a lot of terrestrial fibre-optic infrastructure in Africa — over a million kilometres by some accounts. (Have a look at this map to get a sense of just how much there is.) But much of that fibre is underutilised and the chief barrier to its utilisation is not demand but price.

In East Africa, you can expect to pay between US$25 and $100 per megabit per second for terrestrial wholesale capacity depending on route, distance and capacity. This is arguably a lot cheaper than it has been in the past, but I want to convince you that the price could be significantly lower to the benefit of all.

National fibre backhaul networks are a tide which raises all ships in the ICT sector and beyond. Lower backhaul network prices make municipal fibre networks more economically attractive for cities outside the main undersea cable landing points. Low backhaul costs make it appealing for new operators to enter the market. And new business models begin to emerge for smaller, non-national operators to extend services into secondary and tertiary cities and towns. Lower backhaul costs affect everyone downstream in the network. So how can we lower prices to unlock the full benefit of fibre backhaul networks?

Where private network operators have built national fibre backbones, they naturally treat it as a competitive advantage. They will make capacity available to other operators, but at a premium. As network owners, they can set whatever price they choose — effectively, whatever the market will bear. And that is perhaps fair enough.

The problem starts when national governments invest in national fibre-optic backhaul networks and use the “market” as a guide to their pricing. They are not treating fibre as infrastructure. What do I mean by that? The Oxford English Dictionary defines infrastructure as “the basic physical and organisational structures and facilities (buildings, roads, power supplies) needed for the operation of a society or enterprise”. Let that phrase sink in a bit: “…needed for the operation of society or enterprise.”

It is in the interest of governments to make the cost of using infrastructure as low as possible to enable the wide variety of knock-on benefits, some of which are intangible, to accrue. We have no problem thinking about roads as infrastructure. Governments either don’t extract revenue from roads because they are an enabler of a million kinds of revenue generation or where they do extract revenue, they recognise the importance of keeping usage costs as low as possible. Roads are important because of the sheer diversity of purposes that are served by them. It is time we started thinking about fibre-optic backbones the same way.

In East Africa, the cost per month per megabit per second for a 155Mbit/s connection — what is known as an STM-1 — is anywhere between $25 and $100. Just to clarify, this is a terrestrial connection from a service point to the nearest undersea cable landing point. In Europe, similar backhaul costs are in the neighbourhood of $1. Yet the cost of network build-out is not 25-100x higher in East Africa. If we were treating fibre-like infrastructure, we would think about how to maximise the value that is derived from the network – that is, maximum usage vs the cost of borrowing the money needed to build and operate the network.

Here is a thought experiment. Let’s suppose a national fibre-optic backbone network costs $100m to build. That backbone cable is made up of several strands of fibre-optic cable. The number of fibre strands varies from deployment to deployment, anywhere from 24 to 192 fibre pairs. We’ll use 96 as an example. Similarly, each pair of fibre strands can be broken down into multiple wavelengths thanks to dense wave-division multiplexing technology. Depending on the sophistication of the technology used to light the fibre, anywhere between 32 and 192 wavelengths can be derived from a single fibre pair. Let’s assume 64 wavelengths. Each wavelength can deliver 10Gbit/s, although technology exists that can deliver 100Gbit/s over a single wavelength. Let’s assume 10Gbit/s. Getting back to our pricing above, 10Gbps represents 64 STM-1s (64x155Mbit/s).

Perhaps it is time for national governments to start treating national fibre-optic backbones as we do other kinds of infrastructure

So, our national fibre-optic backbone would have a theoretical capacity of 96 fibre pairs, each with a capacity of 64 wavelengths, each of which can carry 64 STM-1s. Let’s take our $100m investment and calculate the cost of an STM-1. Roughly speaking, $100m divided by 96 divided by 64 divided by 64 comes out to a total cost of about $250/STM-1. Conservatively, that fibre-optic network has a lifespan of at least 15 years. And, it’s upgradeable! If you asked a small operator whether they would be willing to pay double the cost, roughly $500, for the lifetime rights to an STM-1, plus operating costs of course, do you think they would jump at the chance? You bet they would, especially if that STM-1 was upgradeable.

The problem

But this isn’t how fibre-optic network operators work. They light up enough capacity to match current pricing and estimated demand, which is typically a tiny fraction of the total capacity. From a private sector point of view, this makes sense in terms of controlling capital outlay as well as using scarcity to keep prices high. From a national strategic infrastructure perspective, the same logic doesn’t apply. Would you build an eight-lane national highway and only open one lane? No, because you want all the myriad knock-on economic benefits that accrue from having high-speed, reliable, low-cost transport infrastructure — new businesses, economic growth that is more evenly distributed, industries that service the infrastructure and the infrastructure users (the list goes on). The point is that the overwhelming value in fibre-optic backbones is not in the cables themselves but what they enable both economically and socially. Perhaps it is time for national governments to start treating national fibre-optic backbones as we do other kinds of infrastructure.

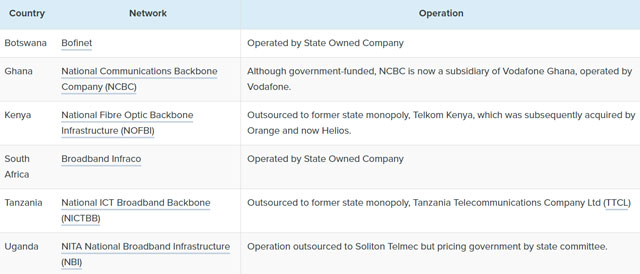

So, what’s holding things back? Across the region, recognising the strategic importance of broadband, governments have financed national fibre-optic backbone projects to extend affordable access to broadband nationwide. While these networks have been successful in extending high-capacity access, they still face challenges in bringing down the cost of access. Typically, to effectively manage these networks, governments have either created state entities to operate the fibre networks or they have outsourced them to private-sector operators to manage. Across the continent, neither strategy has worked well in terms of significantly reducing backhaul costs. Below is a profile of the operation of government-funded national fibre-optic backbone networks across a sampling of countries on the continent:

In Uganda, for instance, operation of the government-owned national fibre backbone (NBI) has been outsourced to a private company (Soliton Telmec) but pricing and access is governed by the National Information Technology Agency. Access pricing is currently higher, in some cases, than can be had from the private sector. In this case, having outsourced to an operator that doesn’t compete directly in the market is a big step forward but it still doesn’t address pricing.

Breaking the pricing logjam

Both the Kenyan and South African governments are considering what to do with their state fibre assets and are exploring options of partial sell-offs or privatisation. This would likely have some incremental impact on competition but, if history is anything to go by, is unlikely to bring prices down substantially. An unexplored option would be to organise the sell-off of government capacity through a special purpose vehicle, or SPV. An SPV is an intimidatingly vague term. In this context, it would be a company set up to represent the fibre assets that the government wants to sell off. The SPV could then seek investors who would have a share in it and in consequence have a share in the fibre-optic capacity of the cable.

The benefit that an SPV would offer is to open investment to a consortium of smaller operators. To make this work, the government would need to create a loan/financing vehicle that would enable smaller operators to participate in the SPV. This is important because where larger operators may not be hungry enough to extend access in underserved areas, smaller operators with lower overheads and access to new, low-cost GSM, LTE, Wi-Fi and dynamic spectrum equipment can build sustainable business models. Key to that sustainability is the cost of backhaul. Owning fibre means they can set their own pricing based on their long-term plans and their expectations of the market. For a small operator, the shift from renting capacity to owning fibre is profound. Speaking to a small Internet service provider in Uganda recently, the chief financial officer told me that the smartest thing they had done as an operator was to invest early in terrestrial fibre.

Driving down the cost of fibre backbones is an essential ingredient in achieving affordable access for all

The idea of launching an SPV consortium within a fibre project is not new. On the east coast of the continent, the Eassy undersea cable established an SPV, now known as Wiocc, with financing assistance from development finance organisations to enable smaller operators to participate in the undersea fibre-optic cable. Similarly, the Teams cable has a Kenyan consortium within the overall structure of its cable ownership structure. I am not aware of this having been tried with a terrestrial cable in Africa, but the same principles apply.

Driving down the cost of fibre backbones is an essential ingredient in achieving affordable access for all. Opening fibre-optic backbone ownership to smaller operators will generate capital that can be used to expand the network, increasing its value. It is also a great strategy for reducing government risk. A consortium approach allows for individual operators to succeed or fail without the government having to pick a winner. This is not the only way to lower backbone costs but it does have the merit of introducing multiple new competitors in backhaul service provision and may stimulate new investment in backhaul networks.

- This piece was originally published on Song’s blog, Many Possibilities. Song is founder of Village Telco

- The author is grateful to several people for excellent feedback, especially Peter Bloom, Jim Forster, Dale Smith and Jon Brewer. While this article does not claim to represent their views, it is much improved for their input

- This column was made possible in part through support from the Network Startup Resource Centre