African telecommunications authorities must walk a fine line when it comes to regulating the move of mobile operators into financial services. They want to encourage this shift, but they also don’t want to be in a position where operators don’t have much oversight.

African telecommunications authorities must walk a fine line when it comes to regulating the move of mobile operators into financial services. They want to encourage this shift, but they also don’t want to be in a position where operators don’t have much oversight.

This is what’s happening in Kenya, where mobile money transfer services like Safaricom’s M-Pesa don’t operate under regulations specifically meant to govern these kinds of services.

M-Pesa was a game changer when it was launched in 2007, not only for Safaricom and Kenya — it enabled the transfer of nearly half of the country’s GDP — but also for African mobile operators.

Prior to M-Pesa, and with the banking system underdeveloped, transferring money around Kenya was onerous. The easiest way to send money from one town to another was to pay a taxi driver to transport the cash.

Although mobile operators had talked about creating a money transfer service for a while, it was wasn’t until Safaricom introduced M-Pesa that talk turned into action. Its success in Kenya proved that the concept of doing banking over an entry-level phone was not only possible but lucrative. About 27% of Safaricom’s revenue comes from M-Pesa.

The excitement around M-Pesa’s potential led Kenyan authorities to hold off on regulating it too stringently.

This is now changing. Concerns over its potential for money laundering and having a single company play such a dominant role in an important part of its economy has seen Kenyan authorities steadily increase regulatory requirements in recent years.

Separate entity

The Kenyan parliament is now even proposing legislation that will see the provider of a telecoms service split its other businesses, like M-Pesa, into a separate entity. This move will eventually see M-Pesa “provide separate accounts and reports”.

The goal is to have M-Pesa fall under the country’s financial services, rather than its telecoms legislation and regulations. Currently, M-Pesa operates under a special licence from the Central Bank of Kenya.

For its part, Safaricom warns that legislative changes could severely affect its operations. “We have noted with concern attempts to regulate the industry through proposed legislation and regulations that seek to forcefully reorganise the operating structure of companies such as ours, whose growth has been the result of well-executed business strategy,” it says in its 2019 annual report.

It goes on to to say: “Such actions would severely limit the ability of businesses to invest, innovate and transform lives, which is what Safaricom exists to do.”

Kenyan authorities are pushing for the change in the law, in part because they are trying to undo some of the unintended consequences of having M-Pesa become the dominant money transfer service in the country.

Being the first to set up a mobile money service has given operators like Safaricom and MTN in Uganda considerable power in this emerging market. As the operators own the infrastructure that runs these services, they have the power to limit competition, as pointed out in a blog by Anthea Paelo, a researcher at the University of Johannesburg’s Centre for Competition, Regulation and Economic Development.

The challenge for authorities is in allowing operators to provide these services without having a handful become dominant, in which case they may charge the public steep fees for using the services and squeeze out competition in the market.

This is what Nigerian authorities had in mind when the country put together its regulatory framework — for instance, it requires mobile money operators “to connect to the National Central Switch (NCS) for the purpose of ensuring interoperability of all schemes in the system”.

This will mean that no single company will get to dominate the infrastructure when it comes to transfers.

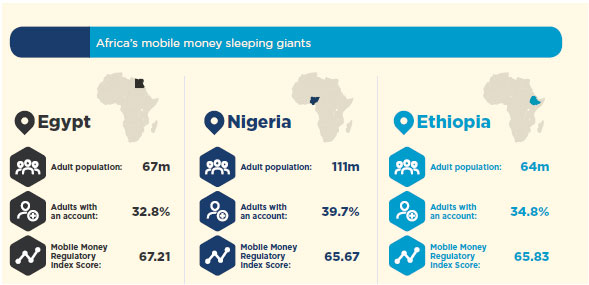

Whatever approach regulators take will have far-reaching consequences. A 2018 survey by the GSMA found that Nigeria, Ethiopia and Egypt, the continent’s most populous countries, are expected to sign up 110 million new mobile money accounts in the next five years.

- This article was originally published on Moneyweb and is used here with permission