From its punchy opening, a cinemagoer who goes to see The American knowing little about the film might expect to it keep up the brisk pace of a contemporary espionage actioner like the Jason Bourne trilogy throughout its running time. It’s best to set that expectation aside.

In reality, the ponderous George Clooney vehicle harks back to the brooding existential thrillers of the 1960s and 1970s, films that were about mood and texture rather than plot and motion. This is a film about the meaningful silences and glances between the gunfire rather than about the gunshots themselves.

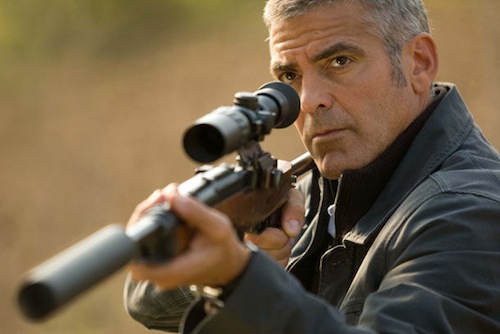

The explosive opening first few minutes of the film see Edward (Clooney) and a lover caught up in a firefight with some Swedes in a snowy woodland clearing. Edward (or Jack, as he sometimes called) escapes to Italy, where he hides out in a small mountain village in the Abruzzo region. Here, Edward agrees to finish off one last job for his handler before his retirement.

Director Anton Corbijn takes this rather clichéd setup and uses it to fashion a case study about a paranoid, lonely man seeking his way out of a violent past. It is not important who the Swedes are or why they want Edward dead. It does not matter who Edward works for. The American is not that kind of film. It is as sparse on dialogue and backstory as it is on action. Its characters are running from pasts are that are not clearly defined or explained, but they live completely in the present moment.

I wanted to like The American far more than I did. Mature, slow-paced films that dare skirt around Hollywood convention and that favour character over action are all too rare in a market driven by big-name sequels and CGI vehicles. It seems churlish to turn one’s nose up at such a film when one arrives.

But there is something deeply unsatisfying about The American. Many critics have compared The American to the films of Jean-Pierre Melville, the influential French director of Le Samourai and Le Cercle Rouge, and to those of spaghetti Western maestro, Sergio Leone.

Corbijn’s silences do not speak as eloquently as those of Melvillle and Leone — filmmakers who don’t seem to waste a frame even when nothing much is happening in their films. His film feels inert rather than contemplative, with little sense of the creeping menace that it needed to draw the viewer into Edward’s world.

And there are simply too many holes in the plot and too much inexplicable behaviour by the film’s characters for it to ring emotionally true. I couldn’t, for example, buy into the relationship between Edward and a village prostitute that the film hinges on. The film’s characters aren’t simply ambiguous or mysterious — some of them seem to be empty under their designer suits.

That said, The American points to a promising career for its director, currently best known for music videos for the likes of Metallica and for a critically acclaimed biopic about Joy Division’s Ian Curtis. The American is beautifully filmed, with many shots of rugged countryside and a quaint village that would no doubt bring busloads of tourists into Abruzzo if more than a handful of people were to see the movie.

And he also coaxes decent performances from the mostly European cast that surrounds Clooney in the American, despite the fact that their characters offer them little to work with. As the assassin for whom he is making a custom firearm, Dutch actress Thekla Reuten is the cold professional that Edward once was.

Violante Placido as the naïve and good-hearted prostitute who Edward looks to for salvation manages to colour her stock character with eroticism, charisma and warmth. Paolo Bonacelli as local priest Father Benedetto turns in a credible performance in as a spiritual man haunted by a secret of his own.

The American — trailer (via YouTube):

Naturally, it’s Clooney who dominates the film. With The American, he reaffirms his status as one of Hollywood’s more adventurous big names. With flecks of grey in his hair and age lines beginning to crease his skin, Clooney embodies the world-weariness of a character that has reached the end of the road.

With little dialogue to work with, Clooney uses the subtlest of gestures and facial expressions to convey the anguish of a man that has started the long crawl to redemption. In his immaculate Ermenegildo Zegna suits, Clooney cuts as much of an iconic figure as Alain Delon in Le Samourai. Sadly, his film doesn’t offer as much substance under the style. — Lance Harris, TechCentral

- Subscribe to our free daily newsletter

- Follow us on Twitter or on Facebook