Facebook whistle-blower Frances Haugen has bequeathed to the world a trove of documents about the downsides of social media. What the internal records show, she told the US senate last week, is that Facebook’s leaders “have put their astronomical profits before people”.

Facebook whistle-blower Frances Haugen has bequeathed to the world a trove of documents about the downsides of social media. What the internal records show, she told the US senate last week, is that Facebook’s leaders “have put their astronomical profits before people”.

This is, of course, true. It is also unsurprising. Facebook is a public company that aspires to maximise profits for its shareholders. The Atlantic’s Derek Thompson argues that social media is “attention alcohol” — a product that is fun but addictive, and “unwholesome in large doses” — and the metaphor is even more apt than that: Beer, liquor and wine manufacturers and distributors also put profits over people.

The difference is that, for the most part, they don’t pretend otherwise. There are all kinds of businesses, whether they’re making potato chips or reality TV, which thrive by taking advantage of human foibles and weakness. One of the things that makes Facebook exceptional — and helps explain the disgruntlement of many employees — is the refusal of Facebook’s leadership to acknowledge this obvious fact.

In the minds of anti-capitalists, the profit motive at the beating heart of the US economy is an indictment of the entire system. I remember being captivated and entertained by the 2003 documentary The Corporation, which quotes an FBI expert saying that if a corporation were a person (in more than just a legal sense), its single-minded focus on shareholder value would qualify it as a psychopath.

Then I grew up and realised that industrial capitalism and the market economy have actually driven huge improvements in living standards. At the same time, it is true that the basic purpose of a business is to make money, even if doing so is bad for your cholesterol (think of those potato chips again) or degrades civic life by undermining the economics of local news (consider the rise of Internet advertising).

High-minded

Which brings us back to Facebook. What’s fascinating about the company is that it is held to an unfairly high standard not only by its critics, but also by its own executives.

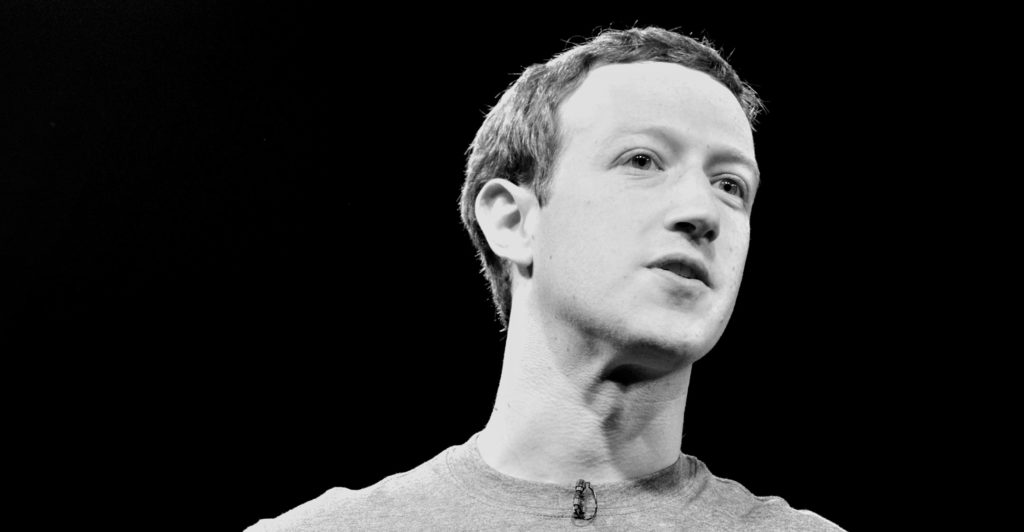

Founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg angrily denied Haugen’s complaints as “just not true”. Speaking on behalf of Facebook employees, he said: “At the most basic level, I think most of us just don’t recognise the false picture of the company that is being painted.”

I know people who formerly worked on various worthy-sounding Facebook initiatives —and they confirm both Haugen’s charge and Zuckerberg’s response. In practice, Facebook is not interested in making any changes that would result in users spending less time on Facebook, regardless of what other positive impacts those changes might have. Meanwhile, the rank-and-file employees with in-demand technical skills who make the company run actually do believe that they are engaged in something more high-minded than making potato chips.

This is an idea deeply embedded in Silicon Valley culture. In 1983, when Steve Jobs was recruiting then-Pepsi executive John Sculley to Apple, he famously asked him: “Do you want to sell sugar water for the rest of your life, or do you want to come with me and change the world?”

This is an idea deeply embedded in Silicon Valley culture. In 1983, when Steve Jobs was recruiting then-Pepsi executive John Sculley to Apple, he famously asked him: “Do you want to sell sugar water for the rest of your life, or do you want to come with me and change the world?”

Technology companies clearly have changed the world in ways that soft-drink companies have not. But today’s tech giants aren’t exciting start-ups anymore. Some still tackle big, tough technical problems (think of Google and self-driving cars), while others find niches of genuinely idealistic behaviour (think of Apple’s consistent drive to deliver world-best accessibility features for the blind). But no company is idealistic enough to compromise major profit-and-loss considerations for humanitarian concerns; ask Apple about human rights in China, for example.

And what about Facebook? Its core business may well be closer to selling sugar water (or potato chips) than it cares to admit. It’s pretty clear by now that the invention of mass-produced sweeteners has been a decidedly mixed blessing for humanity — contributing to major health problems like obesity and diabetes, but also delivering doses of genuine pleasure to billions of people daily.

Nobel laureate Paul Romer’s idea of a progressive tax on digital ad revenue to discourage gigantism makes a lot of sense

If you tried to ban sugar, there’d be an uprising. Whether it should be regulated is another question, but there is no such hesitation when it comes to regulating social media. Nobel laureate Paul Romer’s idea of a progressive tax on digital ad revenue to discourage gigantism makes a lot of sense, but it would be neither desirable nor possible for a federal agency to micromanage content moderation decisions by private companies, as so many seem to want.

Meanwhile, Facebook’s best strategy going forward might be to acknowledge the banal nature of its business. Like everyone else, it has products with pros and cons. All it really cares about is getting more people to spend more time using them.

Such an admission would cause quite a PR headache, of course. But the larger issue is whether Facebook’s recruiting and retention efforts could handle that kind of bracing honesty.

Uniquely vulnerable

To return to those potato chips: Nobody drags American Big Snack executives before congress and accuses them of “putting profits before people”, even though everyone pretty much agrees that selling highly processed snack foods is not a particularly beneficent act. On the other hand, the junk food industry does not necessarily have its pick of the top graduates of the top schools every year.

If Facebook admitted that it is essentially selling a digital version of sugar water (or potato chips, or any other suitably unhealthy alternative), it might attract less negative attention. But more of its employees might be inclined to jump ship. They could form or join exciting start-ups that better align with their values. Or they could or just to go work infusing non-tech companies with much-needed technical skills.

It may be that, while all giant companies are in some sense putting profits over people, Facebook itself is uniquely vulnerable to this critique. Its core product is not tangible, like Apple’s or Amazon’s, and not obviously useful, like Google’s. If that is the case, then a smaller, less influential Facebook might be a net benefit for the world.

It’s unlikely that Zuckerberg would agree — or, for that matter, that he would be willing undergo any exercises in brutal corporate self-reflection. Not so long ago, after all, he himself was a smart, hard-working, idealistic young Ivy Leaguer. He understood the potential of Facebook at a time when few did, and no doubt he sincerely believed that creating peer-to-peer interconnections at scale would have a more unambiguously positive social impact than turns out to have been the case. Still, it’s a heck of a great business.

Over time, many corporate titans conclude that the relentless pursuit of shareholder value simply isn’t that satisfying once you’re already unimaginably rich. Bill Gates long ago stepped down from Microsoft to focus on charitable pursuits, following a trail blazed by Andrew Carnegie and other so-called Robber Barons of the distant past. Zuckerberg has the Chan-Zuckerberg Initiative, a foundation he started with his wife Priscilla Chan in 2015, but for now he is very much involved in the day-to-day operation of his company and the endless series of controversies it generates.

The debates about those controversies tend to careen between absurd self-puffery and uninformed criticism. If the company — and its employees, starting with its first one — were more honest about what they do, then maybe the world could have a less fraught, more sensible conversation about the nature not only of Facebook but of social media itself. — (c) 2021 Bloomberg LP