The response to this week’s unexpected wave of rolling blackouts load shedding — by practically everyone — has been completely unimaginative. Predictably so.

The response to this week’s unexpected wave of rolling blackouts load shedding — by practically everyone — has been completely unimaginative. Predictably so.

They were ‘unexpected’ because, until Sunday morning, there really was zero indication from Eskom that the scenarios it had forecast nearly 10 weeks ago, before the December break, were accurate. At that stage, we were told to expect possible shortfalls from the middle of January. Since then, the utility hasn’t said much at all, save for the quietly published system status bulletins (which most of South Africa has ignored).

Stage-2 load shedding is fairly manageable. Anything above that translates into utter chaos, because of the frequency of cuts and the sheer number of areas without power at any given time.

While the president and government’s top priority is, rightfully, to stabilise Eskom, the second priority ought to be keeping the disruption to the economy to an absolute minimum. Energy analyst Chris Yelland estimates that stage-2 load shedding costs the productive economy R2-billion/day.

Yet there is absolutely no coordinated response to this crisis. Entire cities sat gridlocked for vast periods of Monday and Tuesday (much like they did months ago during the previous rounds of load shedding).

Why is there no coordination, particularly in the biggest five metros, Johannesburg, Cape Town, Ekurhuleni, Tshwane and eThekwini? Three of these are in what the provincial government loves to call the “Gauteng city region”, but the province has been completely silent.

Robotic, inconsiderate scheduling

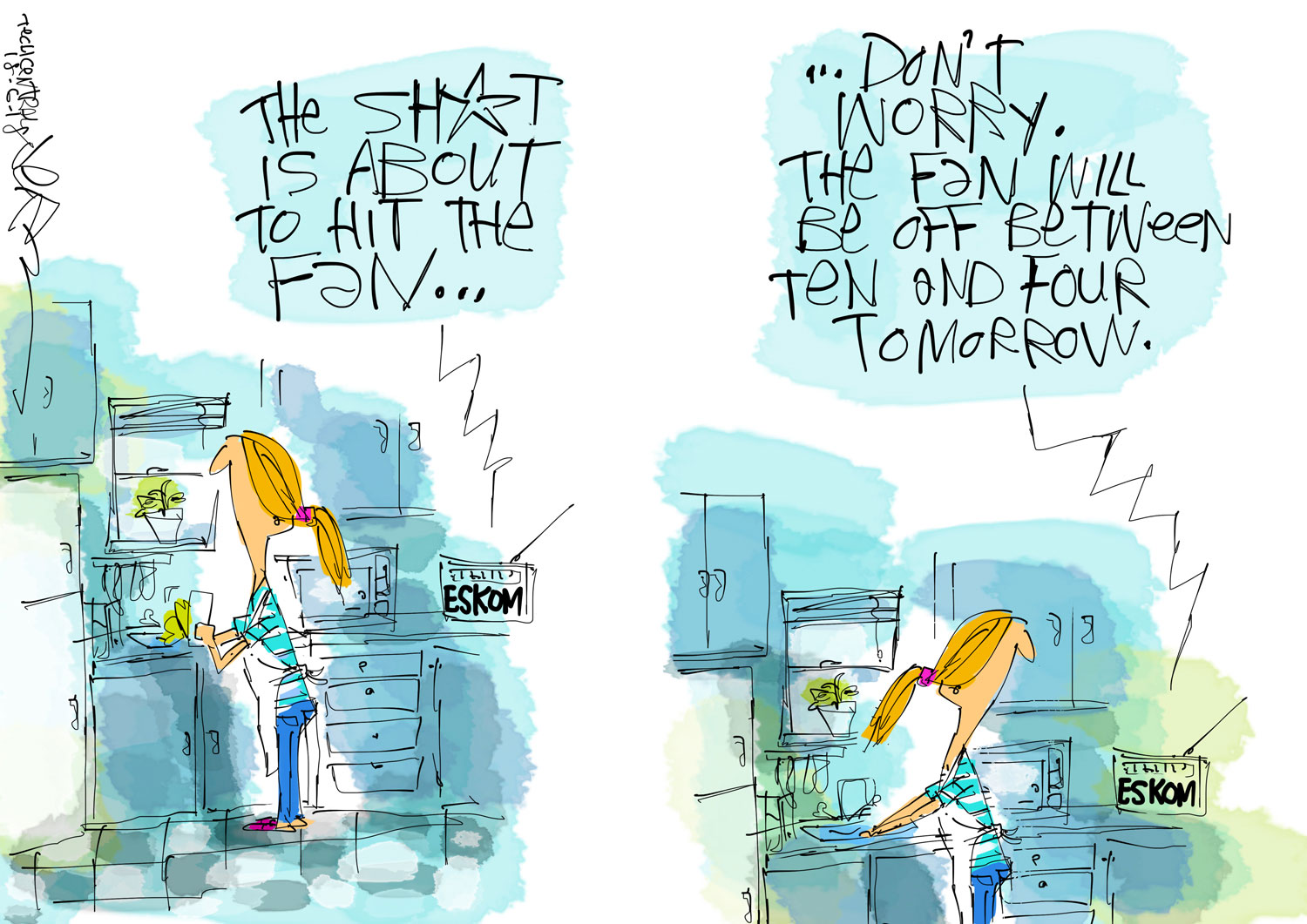

Instead, we have robotic, inconsiderate scheduling that fails to appreciate the contexts and relative importance of different areas. Eskom and the metros will hide behind the fact that the schedules are “equitable”, but this is one of those situations where it literally doesn’t pay to be equitable.

A coordinated effort should be in place to get people to and from the major economic hubs (CBDs and industrial areas) in the major metros with as little disruption as possible. Transport corridors are well understood. Well over 100 000 people drive into Sandton each day. A far bigger amount travel to the Johannesburg, Pretoria, Durban and Cape Town city centres, from where they travel onward to their places of work.

Why has logic not prevailed when it comes to the scheduling of load shedding in these areas during the morning and (particularly) afternoon peaks? There is no value in the whole of Sandton sitting in gridlock because of load shedding between 4pm and well after 7pm (as is the case). The same is true of multiple other hubs.

Most companies and landlords — and small businesses — have adapted to load shedding and are able to be productive while the lights are out. Schedule cuts in these areas during the work day.

Most companies and landlords — and small businesses — have adapted to load shedding and are able to be productive while the lights are out. Schedule cuts in these areas during the work day.

Traffic light outages due to load shedding may be unavoidable in South Africa (apparently California and New York City are somewhat ahead of us in this regard). So why are points people not deployed to the 50/80/100 most critical intersections in each city at a time to keep traffic flowing? Instead, we sit back and rely on the existing services (which lurch from one round of contract or procurement uncertainty to the next) to do the job. There are tens of millions of unemployed South Africans. Find R50-million to deploy to this cause, and if the crisis continues, find more money. Our politicians and civil servants have been able to completely avoid processes under the pretense of “emergency procurement” for far larger sums of money. This is an emergency. Treat it as such.

Then there is the issue of very little consistency between the schedules published by Eskom for directly supplied areas, such as greater Sandton and Soweto, and the metro municipalities. Some run four-hour blocks (thankfully Eskom and City Power are aligned, without which there’d be almost permanent chaos in Johannesburg), others two-hour blocks. The City of Cape Town, confusingly, referred to the “upper” two stages as 3A and 3B.

Having lived and worked under both regimes – two-hour and four-hour blocks – the latter is far easier to plan around due to the simple fact that cuts in areas are less frequent (and there are far fewer faults/human errors when it comes to restoring supply). This coordination should extend to standardising and aligning these schedules across major economic hubs.

Horrified

Eskom itself hasn’t exactly done an adequate job communicating. The entire country seemed horrified by the sudden escalation to the “unprecedented” stage 4 on Monday, without realising that it was the old stage 3, under a new name. The utility quietly revised its load-shedding regime in November and introduced an intermittent stage (3GW) above stage 2. It also added stages all the way up to stage 8, as a “prudent system operator”.

Barely anyone knows this, which is squarely the fault of Eskom. On Monday and Tuesday, many news outlets ran breathless reporting about the “unprecedented stage-4 load shedding”, without recognising that we’ve been here before (many, many times).

Communication about load shedding has been broken since it first reared its disruptive head in 2007 (12 years ago).

In December, public enterprises minister Pravin Gordhan said bluntly: “We must apologise that Eskom does not communicate effectively. Sending out a tweet about load shedding is not communicating.”

In truth, things haven’t got any better.

The entire country sits on tenterhooks each morning, waiting for Eskom spokesman Khulu Phasiwe to tweet the prognosis for the day. And it will be thus.

Why aren’t there two briefings a day — coordinated by the national government to keep South Africa updated — allowing us to all plan around this inconvenience?

We can easily halve the cost to the economy with just a little thought and effort.

- This article was originally published on Moneyweb and is used here with permission