It may seem a trivial matter, but the significance of the decision by new Eskom group chief executive Phakamani Hadebe to reintroduce weekly system status bulletins cannot be overstated.

On Thursday, at the launch of the first system status report to be released in more than three years, he said: “I believe that transparency is one of the solutions to our goal of building trust. The second one is to deliver honestly on our mandate of delivering electricity to power our nation’s economy.”

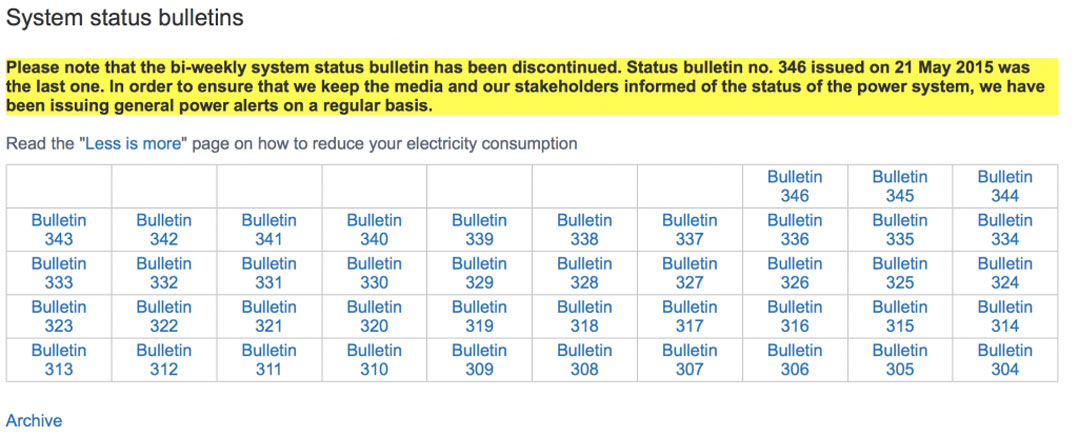

It’s worth considering the historical context of these updates to understand the significance of Hadebe’s move. The first system status bulletins were released in January 2012, as then-CEO Brian Dames tried to ensure that information about the power system was made available in a “regular and transparent” manner. Issued on Mondays and Thursdays, they provided a forecast of peak demand and supply for the week or weekend, as well as actual demand and supply data for the preceding days.

The bulletins offered an accurate glimpse into the health of Eskom’s generation fleet, which in 2014 and 2015 was largely incapable of meeting peak demand. The crisis reached near-breaking point in April 2015, when then-minister of public enterprises Lynne Brown briefed the media on the “state of the grid”. By then, stage-two load shedding was in place almost every day from 6am to 10pm. Because of plant breakdowns and outages, Eskom could no longer even meet demand through the day, never mind peak periods. (Years later there exists a school of thought which argues that much of this load shedding was “manufactured” to create a crisis.)

Brown “seconded” Brian Molefe to Eskom as acting CEO on 17 April 2015. Suspended CEO Tshediso Matona and Eskom “parted ways amicably” on 18 May 2015. The last system status bulletin was published on 21 May 2015.

It must be remembered that this communication ceased in the midst of utter chaos at the utility. During Molefe’s tenure (officially September 2015 to May 2017), communication from Eskom resembled that of the Soviet Union. At times, it arguably verged on Stalinist.

While both energy regulator Nersa and Statistics South Africa publish generation and statistics data, these are at best monthly reports, released months later. This means we’ve had very limited insight into the power system, save for what Eskom chose to release at its infrequent (roughly quarterly) media briefings.

As recently as three months ago, Eskom had a major coal crisis which nearly went unseen. Thanks to persistent questioning by EE Publishers’ Chris Yelland, Eskom finally admitted that it had been burnt R140m of diesel in March alone to run open-cycle gas turbines in order to keep the lights on (more detail in this Mail & Guardian report: Eskom burning through diesel again).

This is why Hadebe’s decision to reintroduce Eskom’s system status updates ought to be applauded widely and loudly. The amount of information provided is also significantly more than that previously released by the utility.

The system status report for week 22 (28 May to 3 June 2018) shows the following:

- Peak weekly demand in the year to date was 34 147MW. This is 3.43% lower than the peak of 35 361MW experienced last year.

- This peak (so far) was hit in week 22, and Eskom relied on “demand response” to remove 398MW of demand from the grid (in effect, large industrial customers reduce load in seconds when/if required to do so by Eskom).

- Eskom’s energy availability factor is at 77.26%, the highest this year (remembering, of course, that Eskom does most of its maintenance in summer months, when demand is lower).

- At the end of March, 30% of Eskom’s generating plant was unavailable.

- Eskom has sent out 1.19% less electricity so far this year, when compared (year to date) to 2017. If its financial year is used (from 1 April), it has sent out 2.07% less electricity than in the 2017 financial year.

- Eskom’s installed capacity is 46 964 MW (this excludes independent power producers/renewables).

- The prognosis for the rest of winter is positive, with no forecast risk of load shedding.

- This article was originally published on Moneyweb and is used here with permission