Terry Lundgren and Kevin Ryan know and like each other. But when it comes to the future of retailing the boss of Macy’s, an American department-store giant, and the chief executive of Gilt Groupe, an online retailer, disagree wildly. Lundgren remains a firm believer in an empire of bricks and mortar. Ryan is betting big on online-only selling.

“It used to be catalogues killing physical stores, then it was TV shopping and now it is online retail,” says Lundgren. Although he will not be pinned down on whether the Internet is a threat to shopkeepers or an opportunity for them, he is convinced that his chain is on the right path. Macy’s is embracing “omnichannel” integration, that is, selling stuff on television, through mail-order catalogues and online, as well as keeping its department stores. The company runs 810 shops across America under the mid-price, mid-market Macy’s brand and 38 posher Bloomingdale’s outlets.

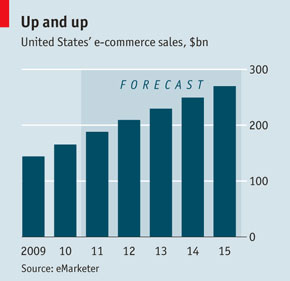

Ryan argues that bricks-and-mortar shops are gravely threatened by Amazon and other online-only retailers, and says he can see “no evidence that there are big opportunities for traditional retailers in online retail”. Overall, retail sales in America are pretty flat, so the double-digit growth of online sellers is coming at the expense of physical shops. Amazon’s sales in the past year were US$48bn, compared with Macy’s $26bn. Last year online sales in America reached $188bn, about 8% of total retail sales. They are forecast to reach $270bn by 2015 (see chart).

So far, however, Lundgren has good reason not to worry that the sky is falling. On 21 February, Macy’s reported fourth-quarter figures that were better than many analysts had expected. Revenue was 5,5% higher than a year earlier, at $8,7bn. Net profits were up by 11,7%, at $745m. Most relevant for Lundgren’s debate with his friendly rival, online sales from the websites of Macy’s and Bloomingdale’s jumped by 40%.

This reflects Macy’s efforts to expand its online business. In January last year, it said it would add nearly 3 500 full-time, part-time and seasonal staff to its online team. It is building a new logistics centre for online sales in West Virginia and expanding an existing one in Tennessee. And it is fixing a shortcoming in its Internet-sales operation: until now online shoppers have only been able to buy goods in Macy’s warehouses; soon they will be able to order items from the stock of its stores.

Magic mirrors and Facebook friends

Lundgren is keen to continue experimenting with ways to use the Internet. In 2010, Macy’s introduced a virtual fitting room where customers tried on digital representations of clothes through their reflection in a “magic mirror” and shared them with their friends on Facebook. “It didn’t work,” admits Lundgren. So Macy’s is now trying out virtual mannequins.

With its thriving Internet business, Macy’s is ahead of many other retailers. Walmart, the world’s biggest, waited for a long time and dithered over its online strategy until it finally decided to “make winning e-commerce a key priority”, as Mike Duke, its chief executive, puts it. After the takeover last year of Kosmix, a social-media technology platform, Walmart created @WalmartLabs, a hub for digital innovation in retailing. It is also pushing e-commerce abroad. On 19 February, Walmart said it would buy a controlling stake in Yihaodian, a Chinese shopping website.

Like an increasing number of store chains, Walmart is inviting online shoppers to pick up their purchases from its physical stores if that suits them. Since last June they have been able to do so on the day they place their order. Now, says Joel Anderson, who runs the company’s online business, more than half of Internet orders are collected from stores. The company claims this is saving shoppers millions of dollars in delivery charges. Those who do not live near one of the 3 800 Walmart shops can opt to collect their purchases from one of 660-odd FedEx locations across America.

Like an increasing number of store chains, Walmart is inviting online shoppers to pick up their purchases from its physical stores if that suits them. Since last June they have been able to do so on the day they place their order. Now, says Joel Anderson, who runs the company’s online business, more than half of Internet orders are collected from stores. The company claims this is saving shoppers millions of dollars in delivery charges. Those who do not live near one of the 3 800 Walmart shops can opt to collect their purchases from one of 660-odd FedEx locations across America.

In spite of these recent improvements, Walmart is not yet reaping big profits from its online business. It does not break out its Internet sales from the total, but they are still tiny for its size. On 21 February, the company reported a 6% rise in revenue for the fourth quarter — but a 15% slump in profits. The increase in revenue had been paid for with steep price cuts.

There are some retailers, in particular those at the extremes of the market, that can safely ignore the threat from shoppers’ migration to the Internet. At the luxury end, Yves Saint Laurent is unlikely to start flogging its ball gowns over the Internet; at the cost-conscious end, dollar stores will continue “piling it high and selling it cheap”. But the vast majority of retailers in between may have little choice but to counter the rise of online-only rivals by creating strong Internet operations of their own.

The biggest threat to most of them is Amazon, the undisputed champion of online selling. It has no physical stores, but has an impressive logistical network: it is said to have 34 huge distribution centres in America and to be building 15 more this year (oddly, it refuses to confirm this).

Other online-only retailers have little chance of felling this Goliath. Their best bet is to be distinctive. Ryan’s Gilt Groupe is modelled on France’s Vente Privée, an online shopping club for expensive branded stuff at reduced prices. Gilt Groupe started out in 2007 with eight employees. Today it has 850 staff and has branched out from luxury fashion for women into high-end food, travel and men’s clothes. Its revenue was $600m last year. It is not making money yet, which is why Ryan, who is likely to be eyeing an initial public offering (IPO) in the not too distant future, recently adjusted the focus of the company from investment in growth to profitability.

Ryan’s business has demography on its side. Its customers’ average age is 34. Consumers aged 24 to 35 already do about a quarter of their shopping online, says John Deighton of Harvard Business School. In Deighton’s view, the Internet-retail revolution is over, in that online buying is well established and will only keep growing. However, he says it is unclear how important a sales tool social networks like Facebook and Twitter, to which some online retailers are pinning their hopes, will turn out to be.

Some bricks-and-mortar retailers have already had disappointing experiences trying to sell through social media. Over the past year Gap, JC Penney and Nordstrom have opened and closed storefronts on Facebook. The social-networking site, which this month filed for an IPO, is trying hard to be a top shopping destination for its 845m members. Yet so far people still tend to visit Facebook to socialise with their friends, not to shop or even to browse in online stores.

Shopping by smartphone

What does seem clear is that as personal computing goes mobile people are buying more via smartphones. Four years ago hardly anyone bought things on their mobile devices but today nearly one-quarter of Gilt Groupe’s revenue comes from smartphone shoppers; on some weekends the proportion reaches 40%. Nearly one-third of people living in America own a smartphone, and 70% of these use it to do searches while they are inside a shop, usually to compare prices. “By 2014, mobile Internet will overtake desktop Internet usage for shopping,” predicts Nigel Morris, chief executive of Aegis Media Americas.

Although it is getting ever easier to blow your credit-card limit without leaving the sofa, there are some who still see a future for bricks-and-mortar stores. Darrell Rigby of Bain, a consultancy, says customers often still want to touch, feel and taste products. And sometimes when they want something, they want it now, and will not put up with waiting for a delivery.

The most clued-up shopkeepers realise that they must make the most of such advantages over online rivals, and that to do so they must make their stores more enjoyable places to visit. Macy’s says it is investing about $400m in the renovation of its flagship store on Herald Square in New York City, which it claims is the world’s biggest department store, with 1,1m sq ft (102 000 sq m) of retail space. To this Macy’s will add another 100 000 sq ft, part of which will become the largest women’s shoe department in the world. The enlarged shop will also have 22 dining venues and 300 extra fitting rooms.

In 2010, Macy’s launched a training programme for its more than 130 000 sales people, “Magic Selling”, which coached them to be more helpful and friendlier with customers. It is tailoring the merchandise stocked in its stores more closely to local tastes. During the holiday season it sells Elvis mementos in its shops in Tennessee and Our Lady of Guadalupe ornaments in cities with big Hispanic populations.

Retailers with lavishly furnished stores and helpful assistants will increasingly have to put up with free-riders who come into the shop to check out the products and get some advice, before slinking off to buy them for less online. Shops’ best defence against “showrooming”, as this practice is called, is to stock more own-label items that are not available anywhere else.

Have you got this in my size?

However, there is no single recipe for retailing success in the Internet age. Retailers will need to balance their investment between staff, locations, inventory and online operations, says José Alvarez of Harvard Business School. For some expensive products it makes sense to have a low inventory, a big investment in showrooms, elaborate online operations and well qualified sales people. For more commoditised items it is more important to have a big inventory than a flashy display. Things that are increasingly being bought online must be swept off the shelves to make way for products that people still want to examine and compare before buying.

Whatever priorities retailers set, their physical stores are likely to shrink as the share of sales made online keeps rising. Retailers in America have a surfeit of space. Between 1999 and 2009, the amount of shopping space per person boomed from 18 sq ft to 23 sq ft. The productivity of that commercial acreage slumped after the financial crisis and shows no sign of recovering.

The retailers who will survive the drift online are the ones “listening to the dynamic demands of customers,” says Walmart’s Anderson. For example, his firm recently found out that some of its recession-hit customers want to order on their smartphones but do not have credit cards. So it has let them make their orders online but come into the shop to pay cash.

Walmart’s customers can also now make their shopping list at home by just opening the fridge and uttering “milk, tomatoes and cottage cheese” through voice-recognition software. The list can then be sorted to take account of their local store’s layout, so they can make the shortest possible tour through the aisles. Shopping promises to be more fun and less hassle in future. The best retailers might enjoy themselves too. — (c) 2012 The Economist![]()

- Top image: Rob Young/Flickr

- Subscribe to our free daily newsletter

- Follow us on Twitter or on Google+ or on Facebook

- Visit our sister website, SportsCentral (still in beta)