“You’re a tourist in your own youth,” says Simon (Jonny Lee Miller) to Mark Renton (Ewan McGregor) in a T2 Trainspotting scene that revisits one of the original’s iconic locations — and he’s addressing the audience as much as he is his friend. Like Requiem for a Dream, Trainspotting was partly about how we’re all addicted to something; T2 suggests our popular culture is hooked on its memories of the past.

Alongside Pulp Fiction, Danny Boyle’s adaptation of the scuzzy Irvine Welsh novel defined the mid-1990s zeitgeist. It’s a such a product of its time that a sequel seems as necessary as an Easy Rider revival or a follow-up to A Clockwork Orange.

Yet there’s a strand of self-awareness in T2 Trainspotting that redeems it; it mocks nostalgia as it embraces it. Whose nostalgia is it anyway, given that the young Renton and Simon were obsessed with Iggy Pop, Sean Connery as Bond and other residue of youth cultures that proceeded them?

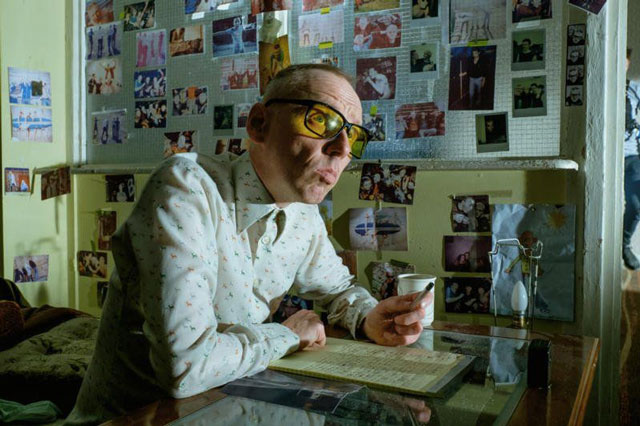

T2 reunites director Boyle with Trainspotting’s original cast, including Miller, McGregor, Ewen Bremner and Robert Carlyle, all of them visibly ravaged by time. Loosely based on Porno — Welsh’s so-so sequel to Trainspotting — the film catches up with junkies and lowlifes Renton (McGregor), Simon “Sickboy” (Miller), Begbie (Carlyle) and Spud (Bremner) two decades after the events of the original film.

Renton is back in Edinburgh for his mother’s funeral, having hotfooted it to Amsterdam with all the proceeds of a big score the reprobates pulled off in Trainspotting. The mostly episodic sequel follows Renton’s efforts to make good with (or at least not be killed by) his former friends, whose lives have turned out much as you would expect from their trajectory in the first film.

Booze-fuelled psycho Begbie is in prison. A seedy, coked-up Simon is shacked up with a young Bulgarian escort (newcomer Anjela Nedyalkova), in partnership with whom he videos rich, unfaithful husbands in flagrante and blackmails them. And the sympathetic, simple-minded Spud is suicidal after failing to kick his heroin addiction and make a successful home life for himself.

Even Renton, the most successful of them, faces divorce, retrenchment and financial ruin. Poignantly, Renton and his friends ache for the very things that he rejected in Trainspotting’s nihilistic “choose life” monologue — the family, the big television, the dental cover and the fixed-interest mortgage. (Appropriately, in T2 he delivers an updated lament about social media, slut-shaming and reality TV to a bored 20-something).

Boyle is canny enough to know that Trainspotting’s cultural impact and youthful vigour cannot be replicated — it was a blast of energy that seemed to come from nowhere. Its gallows humour depiction of shiftless youth abandoned by society captured the underbelly of the Cool Britannia years; it was also a sneering, foul-mouthed rebuke to the tourist postcard image of regal Edinburgh.

Boyle doesn’t try to be as subversive with T2, which is a mellower, more mature picture than its predecessor. The Scots accents are softened somewhat; the hyperkinetic, gimmicky filmcraft is toned down. And the film is infused with the pathos of wasted youth, missed opportunity and the persistence of self-destructive habits.

Rather than wading knee-deep in the faeces, vomit and blood of Trainspotting, T2 is about heart problems, impotence, failed family relationships, the defeat of middle age. It is about what happens to the addicts who don’t die young and become good-looking corpses. If that makes it sound depressing, it’s not.

Though tonally different from Trainspotting, T2 shares its dark, irreverent sense of humour and features some wildly entertaining sequences. One standout sees Renton and Simon improvise an anti-Catholic anthem to distract the members of a Protestant club after robbing them. Even more than that, Boyle has affection for his mostly unlikeable characters, with the luckless Spud emerging as the film’s voice and heart.

The original cast — with Kelly McDonald and Shirley Henderson making all-too-brief appearances — slip into their old roles with minimal effort, but its Bremner’s hangdog look and vulnerability that carries it. There is some form of redemption for most of the characters, even the loutish Begbie, but none deserve it more than Spud. Where Trainspotting was hard-edged, T2 can be downright sentimental.

T2 doesn’t completely satisfy. Compared to the perfect use of music in Trainspotting — who can hear Perfect Day, A Lust for Life or Born Slippy without remembering scenes from the film? — T2’s soundtrack is dull. Where Trainspotting was snappily paced, T2 can go on a bit. Apart from a brief mention of gentrification bypassing Leith, Boyle seems disengaged from the malaise affecting Brexit Britain.

And yes, some of T2’s call-backs to its predecessor are a little too smug. Yet there is no doubt that T2 is a success when seen on its own terms as a reflection on its own legacy and the way the world has moved on since. With cinema in decline, can there be a film again that will shock the senses the way Trainspotting did? Probably not, but there can be one that makes you ask, as Carlyle says: “F**k. What have I done with my life?” — (c) 2017 NewsCentral Media