The Mars One programme is offering civilians, including South Africans, the opportunity to create a human colony on Mars.

Is this a revival of the golden age of discovery, when explorers left their homes to begin new civilisations? Or is it a “suicide mission” in which people die in space while we watch from Earth, more than 200 million kilometres away?

It is the next frontier of exploration: space travel and colonising new planets. Six hundred years ago, explorers took to the high seas, forsaking land for months, on journeys from which they may have never returned. They went in search of exotic, “undiscovered” lands. In 2014, space travel is the new frontier, filled with the unknown and the taste of adventure.

The objective of the Dutch not-for profit Mars One project is simple: to establish a permanent human settlement on Mars. From next year, Mars One will begin training candidates for space travel, until its planned launch in 2024.

Adriana Marais, a PhD student in quantum biology at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, is one of the candidates shortlisted for a one-way ticket to the planet.

“What the first colonisers will do on Mars is really the pinnacle of four billion years of evolution,” she told me.

In her Mars One video, she explains: “I would volunteer to leave my life on Earth behind to see what’s out there. I’m prepared to sacrifice my personal joys, sorrows and day-to-day life for this idea, this adventure, this achievement that would not be mine but that of all humanity.”

And it would be a sacrifice. According to Mars One, which did not want to answer questions and referred the Mail & Guardian to its website, the successful candidates will be those who want to settle on Mars.

“Earth return vehicles that can take off from Mars are currently unavailable, and untested technology and such mission designs incur far greater costs,” it said. “For the astronauts, Mars will be a new home, where they will live and work.”

It would seem, though, that some of South Africa’s candidates are not aware of the harshness of the Martian environment. Asked what they believed their days on Mars would involve, some said they would go for long walks to explore the planet, others that they would be growing food in Mars’s mineral-rich soil.

Magnetic field

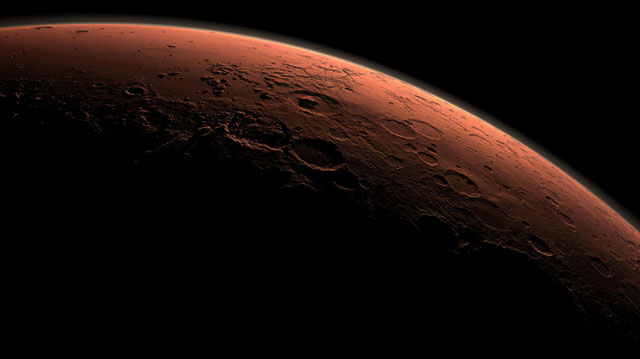

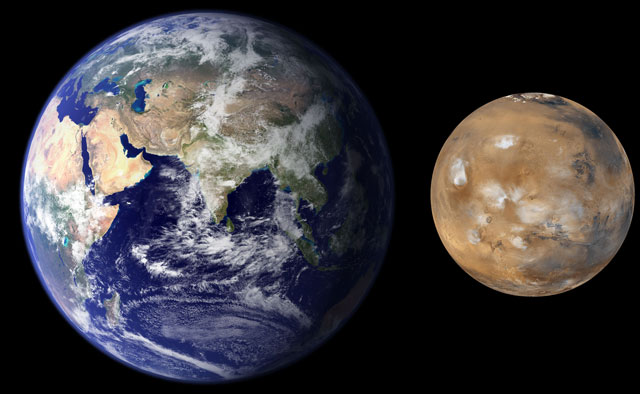

Mars, the fourth planet from the sun, has a very thin atmosphere and no structural magnetic field, although scientists have found evidence suggesting that it once had both. Earth’s magnetic field is the main reason that the planet harbours life — it acts as a shield against the sun’s harsh radiation, which otherwise would kill most biological matter on Earth’s surface.

Radiation on Mars is seen as a major limitation on — and expense for — human travel to the planet, or in space in general.

Last year, scientists from South West University in Texas published data from the Mars Curiosity rover, showing that radiation is a serious threat to astronauts both on the International Space Station and on long-exposure exploratory missions.

“A 500-day mission on the surface [of Mars] would bring the total exposure to about one sievert [a measure of radiation],” the university said.

“Long-term population studies have shown that exposure to radiation increases a person’s lifetime cancer risk; exposure to a dose of 1Sv is associated with a 5% increase in fatal cancer risk.”

According to Nasa’s interdisciplinary guide on radiation and human space flight, “international standards allow exposure to as much as 0,05Sv/year for those who work with and around radioactive material. For spaceflight, the limit is higher. The Nasa limit for radiation exposure in low Earth orbit is 0.50Sv/year.”

Mars One does not list radiation as one of the challenges. It said that the living units will be buried under the soil to shield their inhabitants from it. Rather, the loss of human life and cost overruns are cited as the major concerns.

“Mars is an unforgiving environment where a small mistake or accident can result in large failure, injury and death,” it said. “Every component must work perfectly. Every system (and its backup) must function without fail or human life is at risk.”

The cost is a daunting challenge, particularly cost overruns. Unlike institutions such as Nasa, which has a dedicated government budget, Mars One is crowdsourcing the funding, because it believes “public interest will help finance this human mission to Mars”. The first deployment of humans will cost US$6bn, and $4bn for each successive mission.

Curiosity, with its mobile science laboratory, had a price tag of about $2,5bn.

Tools and equipment

Mars One’s human habitation will begin with a rover, to be launched in 2020. It will be followed by two living units, two life-support systems and two supply units, which will be linked and activated by the intelligent rover.

“We need to send more tools and equipment rather than raw elements,” Mars One said.

“For example, the location for the first Mars One settlement is selected for the water ice content of the soil there. Water can be made available to the settlement for hygiene, drinking and farming. It is also the source of oxygen generated through electrolysis. Mars also has ample natural sources of nitrogen, the primary element (80%) in the air we breathe. Martian soil will cover the outpost to block cosmic radiation.”

Like Earth, Mars has two polar ice caps. Scientists have estimated that, if they were to melt, the surface of the rocky planet would be covered in about 11m of water. Last year, Curiosity discovered subsurface water, with the soil having a water content of about 4% up to the depth of about an arm’s length.

Rushton Drew Carey, a 22-year-old studying accounting at the University of Stellenbosch, told the M&G that survival would be the main focus of his life if he is chosen to go. “Any day on Mars, I’m sure, would revolve around the maintenance of the settlement. I’m sure it would be quite a disciplined lifestyle.”

That disciplined lifestyle would begin on Earth. Crew members will undergo eight years of training and months of being isolated in simulation environments to see how they would cope psychologically.

Similarly, 23-year-old Rhet Evans said: “When we land, it will still take some time for us to become set up with developing our own resources.”

Similarly, 23-year-old Rhet Evans said: “When we land, it will still take some time for us to become set up with developing our own resources.”

The Johannesburg-based computer scientist said that, once they had laid the foundations, “then we will be growing our own crops and terraforming our area to make it liveable … creating a safe haven for us and future Trekkies.”

Mars One claims that the life-support system will be similar to that used on the International Space Station. The living units, each with a total area of 200m2, which is about the size of a tennis court, will house four people, and the different units will be connected by passageways.

“It [life on Mars] would have its challenges but we would effectively be living as subsistence farmers,” 21-year-old Dominic Alexander Schorr said. “Every day would consist of doing routine chores: exercise to maintain muscle mass, tending to the hydroponic farms from which we would get all our food (presumably a lot of soy-based meals), and maintenance and repairs.”

‘Naive’ thinking

Despite Mars One saying that the technology exists to allow people to inhabit Mars indefinitely, Robert Thirsk, a former Canadian astronaut who has spent 204 days in orbit, said that was “naive”.

He told the Toronto Sun in May: “It’s naive to think we’re ready to colonise Mars — it would be a suicide mission. I don’t think we’re ready… We don’t yet have the reliable technology to support a one-way trip to Mars.”

People living and dying on Mars could also pose a problem to space science. Many of the South African candidates say that they would like to be buried on Mars, or to dedicate their bodies or organs to remaining crew members. But this may contaminate the planet.

The Johnson Space Centre, Nasa’s hub for human space flight training, research and flight control, said earlier this year that “organisms hitching a ride on a spacecraft have the potential to contaminate other celestial bodies, making it difficult for scientists to determine whether a life form existed on another planet or was introduced there by explorers”.

In a study published in Astrobiology Journal this year, it was found that some bacteria spores could survive the harsh environments of outer space, creating the possibility that humans could bring other life to Mars.

Kobus Vermeulen, a 31-year-old from Pretoria who has climbed Kilimanjaro and skydived, said that Mars was the next big adventure. He has not romanticised the harsh realities of “yummy dehydrated army food” until the colony has established its food-growing mechanisms or that, if chosen, he would be leaving his old life behind.

“In the end, you are exchanging all those things for new experiences on a new planet … you become part of humankind’s quest for long-term survival in what is, as it turns out, a very hostile universe.”

But there are more than 700 possible candidates for the Mars One expedition. They will be whittled down by next year into “several international teams”, Mars One said in May. Once chosen, the explorers will have full-time training to prepare themselves for the rigours of Mars.

Although Mars One does not say where the candidates will receive their training, it does say that, as part of the final selection, “the groups will be expected to demonstrate their ability to live in harsh living conditions and work together under difficult circumstances … in a copy of the Mars outpost”. This will be televised.

Elon Musk, founder of space transport services company SpaceX, told US television channel CNBC last month that he was hopeful that humans could be taken to Mars in the next 10 to 12 years.

“I think it’s certainly possible for that to occur. The thing that matters long term is to have a self-sustaining city on Mars to make life multiplanetary. That will define a fundamental bifurcation of the future of human civilisation. We’ll either be a multiplanet species and out there among the stars, or a single-planet species until some eventual extinction event, natural or man-made.”

The Mars One candidates believe that they will be helping humanity with this giant leap into the solar system. In the meantime, they wait, sometimes on their own. One South African said that it was “a bit difficult to find a girl who is willing to date a guy who is almost on his way to Mars. I would think that it would actually help the love life but, hey, to no avail.” — (c) 2014 Mail & Guardian

- Visit the Mail & Guardian Online, the smart news source