Exactly 17 days. This is the timeline in which social grant payments to more than 10m recipients will either continue unhindered or the ball will be dropped by the South African Social Security Agency (Sassa).

Imagine how destructive it would be if 70-year-old Roselin Maseko, who is based in Gauteng’s informal settlement of Kliptown, doesn’t receive her old age grant of R1 620 and R1 900 in child support for her five grandchildren (R380 each) to supplement her household income.

In an interview last year, Maseko told me the monthly social grants also support her two unemployed daughters and five grandchildren. This is a microcosm of what is happening across South Africa, which has more people receiving social grants than there are people with jobs.

“If we don’t get our grants, we will be deep in poverty,” said Maseko, a former domestic worker who has been retired since 2008.

A lot is at stake if social grant payments are delayed: South Africa would descend into social unrest, and the livelihoods of recipients, who are already facing the brunt of government’s service delivery failures, would be in jeopardy.

Whichever way the scenario will play out, the manner in which Sassa has handled the phasing out of Cash Paymaster Services’ (CPS’s) invalid contract by 1 April has been, at best, astonishing and, at worst, gross negligence.

Although it has been agreed that the Post Office will take over social grants from CPS, politics has resulted in a half-baked grant payments plan.

Another social grant crisis seems to be unfolding as Sassa appears to be as far from a solution as it was 12 months ago when the constitutional court extend CPS’s contract under duress.

The key protagonist in the crisis is former social development minister Bathabile Dlamini, who has recently been whisked away from the department to the women’s ministry in Cyril Ramaphosa’s new cabinet.

Delays in signing a contract between Sassa and the Post Office, no-shows in Parliament by Sassa and social development officials during inquiry hearings, and a lack of details in phasing out the CPS contract have been largely engineered by Dlamini.

All of this for what purpose you may ask?

Observers have alleged that Dlamini engineered the social grants crisis to pave the way for CPS, a subsidiary of US-Nasdaq listed Net1 UEPS Technologies, to continue to play a key role in the grants payment network. This is despite South Africa’s apex court declaring CPS’s Sassa contract invalid in 2012 as it didn’t go through proper tender processes.

If this was Dlamini’s intention, then it was her parting gift to CPS before she left the social development department. CPS will still be required to distribute a portion of the 10.7m social grants to beneficiaries for six months beginning 1 April 2018.

The constitutional court is yet to decide on CPS’s contract extension.

Under the extended contract, CPS would be the paymaster for only 2.5m elderly and disabled recipients, who receive grants in physical cash as they live in far-flung rural areas and don’t have bank accounts. Dlamini’s delays have led to Sassa not being able to find a service provider that will fulfil this obligation.

Retaining CPS will cost state coffers more. The company currently charges Sassa R16.44/beneficiary to distribute social grants and wants an increase under an extended contract.

Wild and unconfirmed allegations have been made as to why Dlamini was hell-bent on keeping CPS on Sassa’s payroll — chief among them that Net1 provides donor funding to the ANC.

In a February interview with Moneyweb, Net1 CEO Herman Kotzé rejected the assertion that Dlamini favours CPS.

“In the minister’s mind, the last thing she wants to see is for the Sassa system to fail and people not to be paid on her watch. There is something that works like clockwork (CPS) and replacing it without a bullet-proof plan in place is a very daunting task,” said Kotzé.

Post Office

Although the Post Office is ready to play a big role in paying social grants much of its involvement is still in the testing phase — with only two weeks before its systems go live.

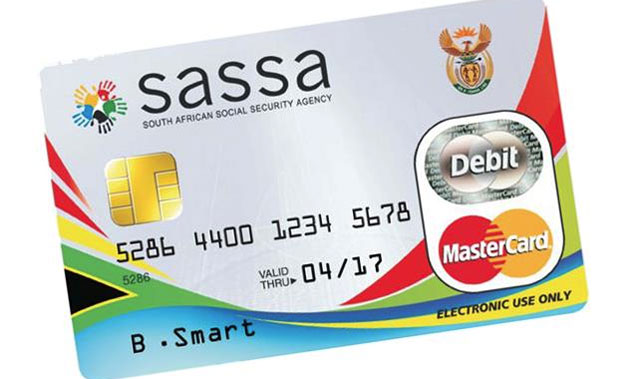

The first release of new Sassa/Post Office cards that 5.7m beneficiaries will use to withdraw their money at 5 000 Post Office outlets, ATMs or retail pay points is only expected to start on 1 April. This timeline might be unrealistic as the new cards must be tested by the Payment Association of South Africa and the Reserve Bank.

Problem number two is that the process for tender bids from service providers that will distribute physical cash to recipients has been delayed, with the deadline revised from 28 February to 12 March and then extended to 30 March. The entire process might only be concluded by July.

CPS is not precluded from participating in this process.

The delays create massive uncertainty as Sassa doesn’t even have contingency plans for physical cash payments if it cannot find a service provider.

Problem number three is that commercial banks, mainly Nedbank, Standard Bank and FNB, will also play a crucial role in the grant payment system by offering low-cost bank accounts that recipients will use to access their grants. However, they are yet to submit their tender bids and be contracted.

Sassa said it has engaged individually with banks for low-cost bank accounts — but Ubank, a small retail bank, appeared more keen to offer its services. Larger banks are unhappy that Sassa wants standardised low-cost bank accounts, which they said would create problems with competition authorities and that each bank prefers to create a unique, low-cost product.

Civil rights group Black Sash, which compelled the court to intervene in the Sassa fiasco, recently said using banks is not an ideal proposal unless the bank charges for recipients are regulated.

Until then, it’s a scary minefield of no credible plan to pay social grants.

- This article was originally published on Moneyweb and is used here with permission