It’s official. BlackBerry, the Canadian company that invented the smartphone and addicted legions of road warriors to the “CrackBerry”, has stopped making its iconic handsets.

Finally conceding defeat in a battle lost long ago to Apple and Samsung Electronics, BlackBerry is handing over production of the phones to overseas partners and turning its full attention to the more profitable and growing software business.

It’s the formalisation of a move in the making since CEO John Chen took over nearly three years ago and outsourced some manufacturing to Foxconn Technology Group. Getting the money-losing smartphone business off BlackBerry’s books will also make it easier for the company to hit profitability consistently.

“This is the completion of their exit,” said Colin Gillis, an analyst at BGC Partners. “Chen is a software CEO historically. He’s getting back to what he knows best: higher margins and recurring revenue.”

Chen should be able to execute his software strategy as long as he keeps costs in line and maintains cash on the balance sheet, Gillis said.

BlackBerry, based in Waterloo, Ontario, gained as much as 7,4% on Wednesday, its biggest intraday jump since December 2015.

BlackBerry said it struck a licensing agreement with an Indonesian company to make and distribute branded devices. More deals are in the works with Chinese and Indian manufacturers. It will still design smartphone applications and an extra secure version of Google’s Android operating system.

“I think the market has spoken and I’m just listening,” Chen said in a discussion with journalists. “You have to evolve to what your strength is and our strength is actually in the software and enterprise and security.”

The new strategy will improve margins and could actually increase the number of BlackBerry-branded phones sold, Chen said, as manufacturers license the name that still holds considerable sway in emerging markets like Indonesia, South Africa and Nigeria.

“This is the way for me to ensure the BlackBerry brand is still on a device,” Chen said.

Although BlackBerry’s latest phone, the DTEK50, was already almost completely outsourced, the move is a big symbolic step for a company that once reached a market value of US$80bn. Today, it’s worth about $4,3bn.

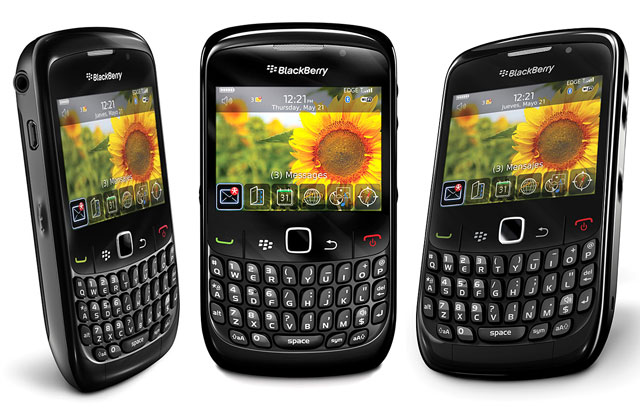

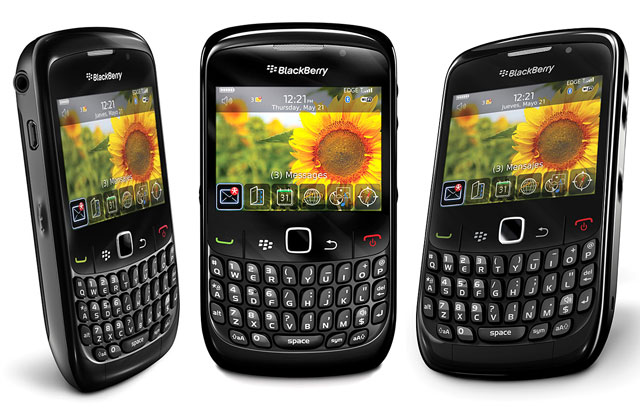

Keyboard fans

When the BlackBerry 850 was released in 1999, it married a functional keyboard with e-mail capability and essentially ushered in the modern smartphone era.

With a proprietary operating system known for its watertight security, the phones became ubiquitous and extended the workday onto commuter trains and into restaurants and homes.

They were an instant hit with business executives and heads of state alike. President Barack Obama was fiercely committed to his, but finally ditched it earlier this year, reportedly for a Samsung.

In 2007, the iPhone debuted with its touchscreen interface and app store. People at first said they didn’t want to give up BlackBerry’s keyboard and simplicity. But the lure of apps eventually sent almost all its users to phones running Android or iOS.

“It was inevitable at this point; they didn’t have the unit volumes to sustain the business profitably,” said Matthew Kanterman, an analyst with Bloomberg Intelligence.

“This is doubling down on the efforts to focus on software which is really what their strength is.”

BlackBerry shipped only 400 000 phones in its fiscal second quarter, half what it sold in the same period last year. Apple sold more than 40m iPhones last quarter.

BlackBerry said software and services revenue more than doubled in the quarter from a year earlier to $156m. Still, software revenue was down from the previous quarter’s $266m, which Chen blamed on patent licensing deals that didn’t carry over into the quarter.

Adjusted earnings were at break-even, compared with analysts’ estimates for a loss of $0,05. Revenue in the second quarter was $325m, falling short of analysts’ projections for $390m. For the full year, BlackBerry expects a loss of $0,05 or to hit break-even, compared with what it said was a current consensus of a $0,15 loss.

While investors appear to be relieved that BlackBerry finally threw in the towel on handsets, Chen will still have to prove that he can continue to expand the software business in an increasingly competitive space.

So far, Chen managed to hit his fiscal 2016 target of pulling in $500m in annual software-only revenue last March. The next milestone is to grow that by another 30% by March 2017.

Chen also aims to expand the margins of software products to around 75% from closer to 60% now, he said.

Competitive threats

BlackBerry’s most important software is its device management suite, which helps companies keep track of their employees’ phones and make sure sensitive communication stays within the business. BlackBerry bought one of its key competitors, Good Technology, for $425m last year, but the market is crowded.

“This doesn’t change the fact that there are still a lot of competitive threats,” Kanterman said in a phone interview. VMWare, IBM and Microsoft all have device management products and are taking market share by bundling them in with other business-focused software they sell.

In some ways, it doesn’t make sense for BlackBerry to stay a public company. Given its shriveled market value, it could be the right price for a private-equity takeover, or it could sell out piecemeal to a bigger company like Dell Technologies subsidiary VMWare or Samsung.

As BlackBerry reinvents itself, it will have to change how it’s perceived in the market. Investors still largely value BlackBerry as a hardware company, not the software provider it has become, Chen said.

“As soon as that message is recognised, the stock will move to the right valuation,” he said. — (c) 2016 Bloomberg LP