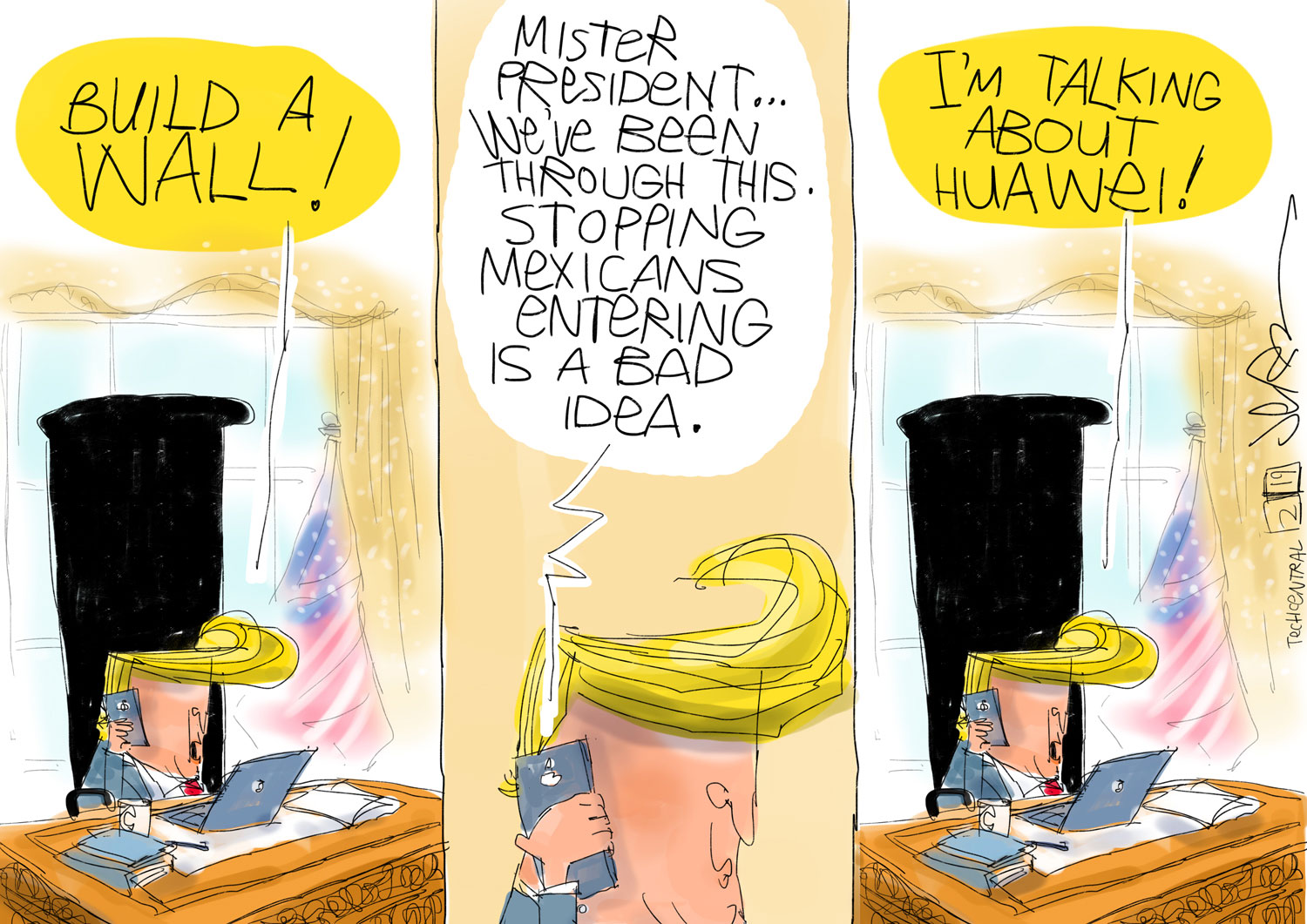

The Bloomberg report of persistent vulnerabilities found in Huawei telecommunications equipment by major operator Vodafone highlights the Chinese vendor’s current problem: while its competitors are given the benefit of the doubt when their products are found vulnerable, Huawei is held to impossible standards for political reasons.

The Bloomberg report of persistent vulnerabilities found in Huawei telecommunications equipment by major operator Vodafone highlights the Chinese vendor’s current problem: while its competitors are given the benefit of the doubt when their products are found vulnerable, Huawei is held to impossible standards for political reasons.

This is a problem that probably can’t be solved on a technical level. Huawei will have to drop any legacy resistance to stringent tests by clients and regulators and make more of an effort to clean up its software, but at the same time European countries in particular should expect subtle pressure from China to treat Huawei like any other vendor. The US isn’t the only country that can play that game.

The headlines that include the words “Huawei” and “backdoor” look damning given the US government’s insistence that American allies view Huawei as a security threat. But it’s not at all unusual for backdoors — software vulnerabilities that allow third-party access to a piece of equipment — to be found in the products of other major suppliers, too. Last year, Cisco Systems — with a long history of its equipment being exploited by US and other spy agencies — removed no fewer than seven backdoors from various products. In February, security firm Tenable Research discovered backdoors in Nokia routers that, like the Huawei vulnerabilities found by Vodafone, allowed potential attackers access via the Telnet protocol.

It’s standard for equipment vendors to warn investors of such vulnerability risks. Here’s the language from Ericsson’s 2018 annual report:

It is possible that a cybersecurity incident in Ericsson’s supply chain could have an adverse impact on Ericsson’s ability to deliver products or services to Ericsson’s customers. These incidents may include tampering with components, the inclusion of backdoors or implants, the unintentional inclusion of vulnerabilities in components or software and cybersecurity incidents… Products and infrastructure used by Ericsson may contain vulnerabilities that can be leveraged by a threat actor. In some situations, it may be impossible to detect these vulnerabilities due to their location, or due to the fact that they are unknown vulnerabilities.

Software is developed by humans, who will, sometimes inadvertently and sometimes on purpose, roll out releases with backdoors in them — often for past or future servicing and maintenance needs. But the telecoms industry’s problem goes beyond human error, laziness and malicious intent. Its fundamental services are based on dated protocols. As the GSMA, the global telecoms operator lobby group, wrote in its most recent threat report, “Many of these protocols are dated and were implemented without an authority model but relied on assumed trust within a closed industry. Couple this insecurity with their essential nature to operate many network functions and any security threats realized against these services will have a high impact.”

Since the protocols will continue to be used, even the most vigilant telecoms operators face high security risks. The widespread reliance on vulnerable open-source software is another source of problems.

But while Western equipment vendors and the mobile operators themselves are expected to deal with these issues to the best of their ability and at their own pace, with inevitable setbacks now and then, that’s no longer the case with Huawei. Any security problem, any failure to detect a backdoor and close it will be used as proof that the vendor is an arm of Chinese intelligence. That imposes tough demands on Huawei if it wants to keep its leadership in the telecoms equipment industry and avoid government bans.

Impermissible

Intention matters. The Bloomberg report has the company telling a major client that it’s fixed a vulnerability when it hadn’t. If that was an intentional deception, that’s bad enough. It was at least a poor decision; but in view of the evolved US position, that kind of thing is impermissible now.

Of course, Huawei’s political problem is not really for the firm to solve. No matter what the Chinese company does, the current US administration will keep going after it for a mix of national security, trade and competition-related reasons which are hard to separate from each other. This requires a pointed response from China, and such a response will undoubtedly follow.

The UK, where Vodafone is based, will be more exposed to the competing US and Chinese pressures than most other countries if it goes through with Brexit. It will lose the EU’s protection but its market is sufficiently large for both the US and China to try to impose their terms of trade. The US is already warning the UK of possible cuts in intelligence sharing if it doesn’t drop Huawei, but if it caves, the probability of a favourable post-Brexit trade and investment deal with China will recede.

The UK, where Vodafone is based, will be more exposed to the competing US and Chinese pressures than most other countries if it goes through with Brexit. It will lose the EU’s protection but its market is sufficiently large for both the US and China to try to impose their terms of trade. The US is already warning the UK of possible cuts in intelligence sharing if it doesn’t drop Huawei, but if it caves, the probability of a favourable post-Brexit trade and investment deal with China will recede.

Even so, Huawei can’t rely solely on its home nation’s support. It needs a conscious effort to build trust. The Chinese vendor might be well-advised to borrow a page from Cisco’s book: the US company is combing systematically through all its software, reporting and fixing the vulnerabilities it finds. That kind of exercise wouldn’t resolve Huawei’s American problem, but it would go a long way toward keeping other clients, major mobile networks, on its side against any government meddling. The Chinese firm is being too defensive and not open enough, and that needs to change. — (c) 2019 Bloomberg LP