The US National Security Agency is normally so secretive that its creation was classified, leading to the nickname “No Such Agency”.

The US National Security Agency is normally so secretive that its creation was classified, leading to the nickname “No Such Agency”.

But in a move that surely caused hand-wringing and murmurs among the nation’s longtime spies, the agency opened its doors to journalists. But just a crack.

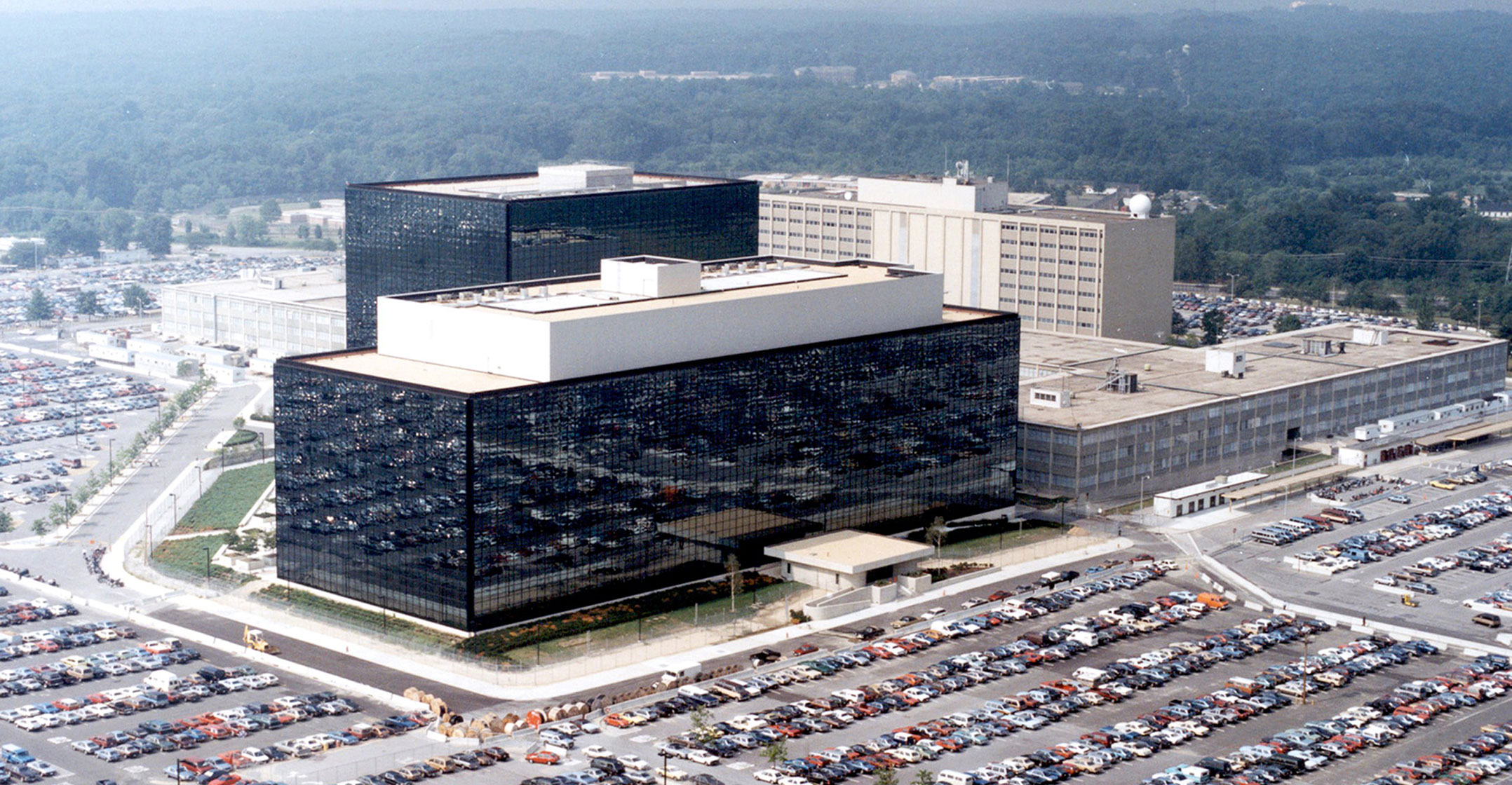

Reporters were welcomed into the agency’s Fort Meade, Maryland headquarters last week for a carefully curated tour. The occasion? The NSA wanted to show off its Cybersecurity Directorate, a newly minted organisation that began operations this month to protect the US against emerging cyber threats.

“This is a little bit of a different approach for us from the traditional No Such Agency approach,” said Anne Neuberger, the head of the new cyber directorate, who was among the handful of NSA officials who spoke to journalists during the two-hour event.

The tour took place on 10 October amid a recognition that US enemies are rapidly developing cyber tools that threaten national security and the private sector alike, according to agency officials.

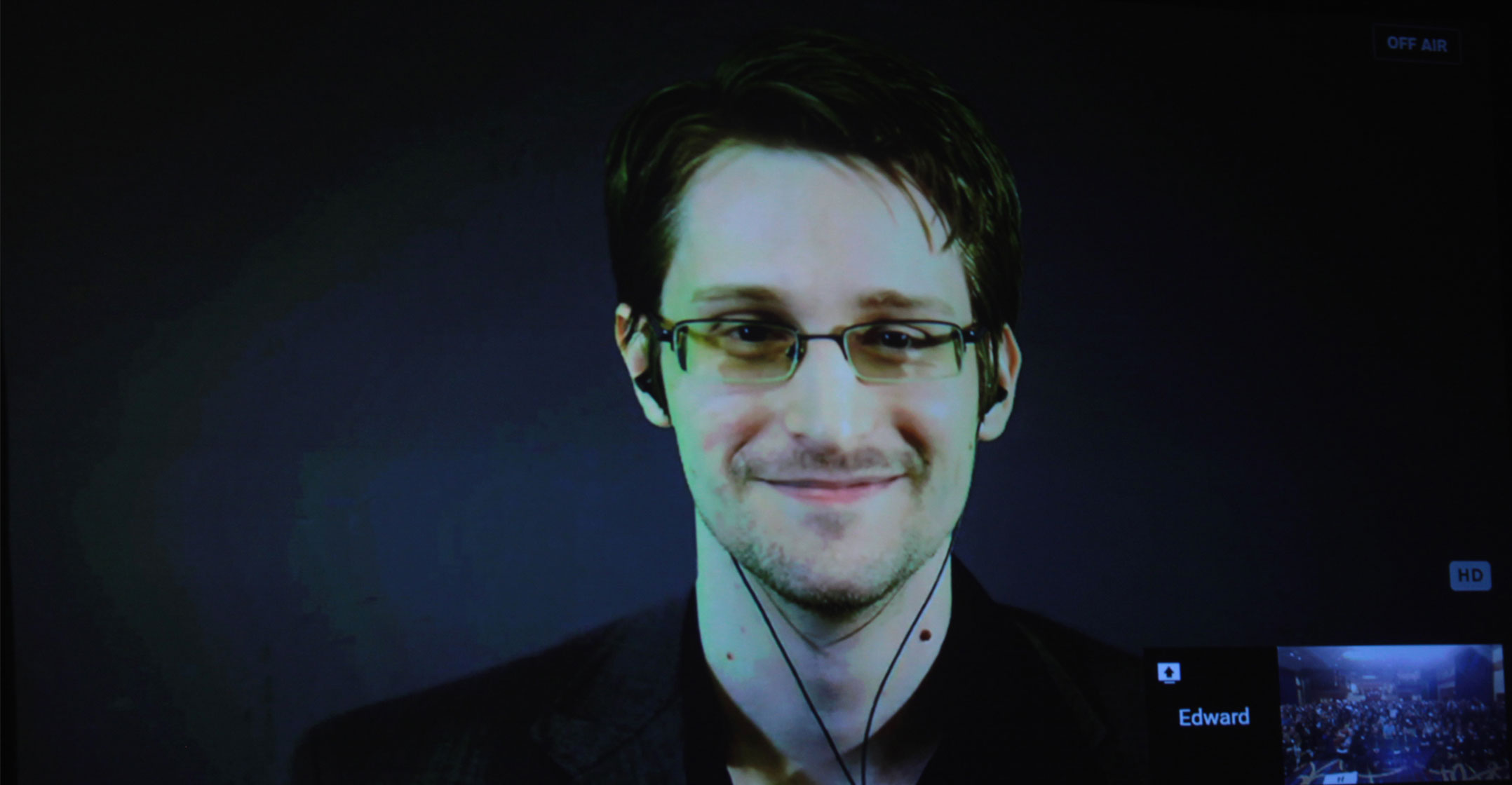

But Neuberger also traced the agency’s new openness to 2013, the infamous year in NSA history when whistle-blower Edward Snowden spilled its secrets. Neuberger, who served as the agency’s chief risk officer following the disclosures, was struck that a surveillance agency has a unique role in a democracy — it should publicly explain its values and the way it balances national security with civil liberties and privacy.

‘Not trusted’

“If we are a black box then a black box is not trusted,” she recalls thinking at the time. “The average American is a thoughtful thinking person, and they want to know what’s in the box.”

Two hours wasn’t much time to examine the box. But it was a start.

One of the highlights came after journalists were led into a conference room where opaque frosted glass panels lined the wall. Then, in a technological feat worthy of a Bond movie, the glass clarified on command — revealing a view, albeit brief, of a newly formed cyber operations centre that had been fogged from sight moments before.

There, the nation’s cyber warriors — some in plain clothes, others in uniform — sit hunched over in semi-circular pods that face six-metre-tall screens, where they search for malicious hackers stalking through the nation’s computers. This “Joint Operations Centre” includes a mix of employees from the NSA and US Cyber Command, the military’s cyber division and is staffed around the clock.

Each 12-hour shift includes a staff of about 200. Besides searching for adversaries, the cyber sleuths defend government networks, share information with government agencies, coordinate with allies and support offensive cyber operations, officials said.

The glass re-fogged 12 minutes later and the hub of cyber activity vanished from sight, a reminder that the NSA’s new transparency policy has its limits.

Creation of the Cybersecurity Directorate is the first major reorganisation of the agency in three years, and it seeks to restore some of the old organisational chart — with a few tweaks. Under the 2016 reorganisation, the agency’s Information Assurance Directorate, which had been responsible for the NSA’s defensive mission, was eliminated and the agency’s offensive and defensive missions were combined.

Since then, the so-called “defensive” challenges facing the NSA have only grown. Advances in quantum computing may soon threaten the security of the US government’s most sensitive communications. And digital adversaries like Russia, China and Iran have grown both more sophisticated and more ruthless.

During the tour, officials said the new directorate does more than resurrect the old IAD. Under the new directorate, cyber defenders will have better access to real-time intelligence collected by the agency’s cyber spies and be expected to defend against attacks by targeting the adversary’s technology.

The directorate doesn’t have an easy task. As the 2020 presidential election approaches, it is responsible for gathering and distributing intelligence needed to defend the vote, punish bad actors and avoid a repeat of 2016 — when Russia meddled with state election data and launched a foreign influence campaign on social media.

‘They need to know’

Beyond elections, new threats to the power grid, financial sector and air traffic safety are arising at an unprecedented pace.

Since new cyber threats affect all Americans, the agency’s ethos — “we don’t talk about who we are, we don’t talk about what we do” — needed to change, too, Neuberger said. In her view, the press could play a role in helping the NSA and the public understand each other.

“If we want the average American to feel that they can trust the best of the country’s intelligence capabilities to be protecting the security and stability we rely on, they need to know the principles we operate under,” she said. “They need to know the questions asked here.” — Reported by Alyza Sebenius, with assistance from Michael Riley, (c) 2019 Bloomberg LP