Digital divide, digital dividend, digital yadi-yadah. You would be forgiven if the term “digital dividend” didn’t immediately resonate with you given the proliferation of all things “digital” in recent years. A quick reminder then.

The digital dividend refers to the spectrum that is freed up in the conversion from analogue television broadcasting to digital broadcasting, a change that has largely already taken place in the industrialised world and is slowly gathering pace in Africa. This involves deploying digital transmitters to replace the analogue ones and either new digital televisions or digital set-top boxes for existing televisions.

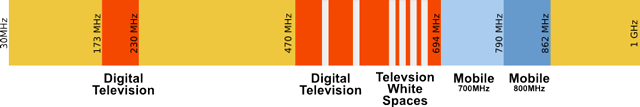

But the fact that more channels may become available or that you can receive television channels optionally in high-definition is less exciting to me than what can be done with the spectrum that is freed up. How much spectrum is being freed up? There is over 400MHz of television spectrum.

Digital broadcasting uses a fraction of the spectrum that analogue broadcasting does and, in Africa, there are few enough analogue terrestrial television channels per country to begin with. What is more, it turns out that television spectrum exists within a particularly attractive range of these frequencies.

What makes a frequency attractive is propagation, or the ability of a radio wave to go through obstacles. The lower you go down the spectrum, the longer the radio waves and the less they are inclined to bounce off solid objects. That means that you can cover a larger area with a single transmitter and that means that the cost of building a communication network drops significantly.

There are trade-offs, however. Longer waves carry less information, so you can’t pack as much data into the same channel, but that is a very reasonable trade-off when it comes to planning rural networks where the cost of network deployment may be a bigger issue than ensuring greater than 20Mbit/s download speeds.

So, the digital dividend spectrum is extremely appealing from an infrastructure cost-of-ownership perspective. It is unfortunate, then, that most of the debate around it has largely been held within the broadcasting community. I’m not saying digital broadcasting isn’t important, but the digital dividend is an extremely valuable resource that needs to be considered holistically in terms of its national strategic value.

At the World Radio Congress (WRC-12) last year, there was confirmation of 790-862MHz (popularly known as the 800MHz band) as a global IMT (mobile) band. There was also a move by some African countries to have the 694-790MHz band (popularly known as the 700MHz band) made available in Region 1 (Africa and Europe) on an accelerated basis, probably because there are lots of CDMA players already in the 800MHz band.

The 700MHz band is likely to be confirmed as an IMT band for Region 1 at the WRC in 2015. That’s good news for mobile operators, except that the release of the 700MHz and 800MHz bands is being treated as contingent on the completion of digital migration. Given the delays that have plagued the migration on the continent, this seems like a dangerous strategy. Why can’t one or both of these two new IMT bands be cleared for use while migration is going on in the lower end of the television spectrum? At the very least, preparatory work for release of this spectrum ought to be going on now.

But the situation is worse than just a disconnect between the broadcaster and mobile operators. There is also the prospect of missing out on an alternative access technology that could make a real difference for rural access. Television white-spaces technology has the potential to create a vibrant rural access industry in Africa.

Television white spaces refers to the guard bands left between analogue television broadcast channels in order to prevent interference. TV white-spaces technology is capable of serendipitously reusing that empty spectrum without interfering with existing television broadcasts. The initial vision was that through spectrum sensing, the devices would automatically use whatever empty spectrum was available, as a secondary user. That means if a television signal suddenly turns on in a frequency being used by a TV white-spaces device, it would automatically cease using that frequency and find another empty frequency to use.

The broadcast and wireless microphone industry in the US were not satisfied with this solution and the concept of a geo-located authentication database was introduced whereby TV white-spaces devices would need to authenticate against a spectrum database to see what spectrum was available for use in the area it was being used.

Very low-power TV white-spaces devices are still allowed to use just spectrum sensing. In general, TV white-spaces regulation in the US has been the victim of massive lobbying and the result is some extremely hamstrung regulation.

The UK has largely followed the US regulations, with one significant improvement. The power output level of the devices is not fixed but can be dictated by the settings in the authentication database. This means that higher power-output levels could be assigned in sparsely populated rural areas versus areas where there are many other spectrum users.

What is exciting about this technology?

- No spectrum licence, or a very nominal one, is required. This means new opportunities for small entrepreneurs to provide alternative access.

- Great propagation. A typical TV white-spaces link can go 8-10km without any effort and is not obstructed by trees, buildings, etc.

- Innovation. Wi-Fi has gone from a niche spectrum for experiments to an industry that is expected to be worth over US$6bn in 2015.

- About 70% of smartphone data traffic in the rich world goes over Wi-Fi. This is what open spectrum offers. TV white spaces has the potential to be another such industry because of the low barrier to entry.

- No spectrum refarming is required. Because TV white-paces technology is designed for secondary use of spectrum, there is no need to move the primary spectrum holder. This is a quick and easy win. Conflicts can be easily resolved by the regulator thanks to the authentication database.

TV white spaces are finally gaining traction, however. Google is sponsoring pilots in South Africa and in Kenya, and Microsoft is supporting a pilot in partnership with the Kenyan government and a satellite operator there.

Those are good signs, but, in general, the discussion of the digital dividend has been trapped in bureaucratic silos. There needs to be a broader acknowledgement of the strategic value of the dividend and a strategy that addresses it holistically.

- Steve Song is founder of Village Telco

- This piece was originally published on Song’s blog, Many Possibilities