If you listened only to social development minister Bathabile Dlamini and the South African Social Security Agency (Sassa), you might believe that last week’s constitutional court judgment vindicated the agency.

Rather, Sassa should be seriously embarrassed, and the judgment should give rise to grave concern about how the agency is being run.

In two judgments — the first delivered in November, the second last week — the court ruled that a R10bn contract awarded to Cash Paymaster Services (CPS) is constitutionally invalid, and that the agency must rerun the tender.

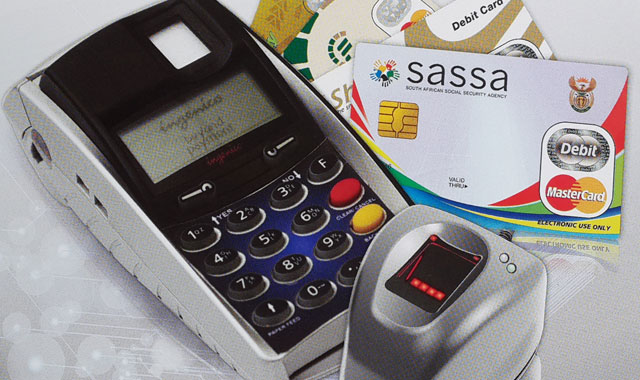

The contract outsources the payment of social grants for about 16m South Africans. To ensure that payments are not disrupted, the court suspended its declaration of invalidity until after the new tender process.

CPS won its contract early in 2012, but was immediately challenged in the high court in Pretoria by losing bidder AllPay.

AllPay lost on appeal, but the constitutional court’s “merits” judgment in November found that the tender process was invalid. Last week’s judgment ruled on how the wrongdoing should be remedied.

Far from vindicating the agency, the court’s decision demonstrates its lack of confidence in Sassa’s bona fides.

Authored by judge Johan Froneman, the order directs that the court effectively hold Sassa’s hand throughout the new tender: Sassa must publicly report back to court at crucial stages.

The court will release its grip on the agency’s arm only when it comes to the final decision: whether to award a contract and to whom it should be awarded is up to Sassa.

If the agency decides not to award a contract, it has two weeks to tell the court whether and when it can take over grant payments.

CPS, the court concluded, “has no right to benefit from an unlawful contract”, so if Sassa does not award the new tender, the company must publicly file its audited financial statements for the contract, and Sassa must independently and publicly verify these.

This is known as a “structural interdict”, when a court imposes a supervisory role on the government.

The judges appear to have grappled with an unusual problem: how should a court act when it cannot be taken for granted that the government will act in good faith?

Froneman said that because millions rely on grants, there is obvious public interest “in ensuring that the tender is rerun properly”.

Implying that the court was not confident Sassa could achieve this, he said “disciplined accountability” would be needed for the new tender, which “needs to be monitored”.

Sternly, Froneman then turned to the agency’s role: “Sassa’s irregular conduct has been the sole cause for the declaration of invalidity, and for the setting aside of the contract.”

He said Sassa’s stance was “unhelpful and almost obstructionist”, and that it had failed to provide crucial information to AllPay and to outline the steps it took to investigate irregularities.

“Its conduct must be deprecated, particularly in view of the important role it plays as guardian of the right to social security and as controller of beneficiaries’ access to social assistance.”

In denial?

Far away on planet Sassa, however, the mood was jubilant.

On Twitter, Dlamini’s spokesman, Lumka Oliphant, said of her principal: “She keeps winning!” To this she added: “No disruption means business as usual at Sassa. 1 – Sassa, 0 — AllPay.”

Dlamini seemed similarly pleased: “Oh Lumka, I slept for only an hour. Can you imagine 16m people without food? The order of no disruption of grants is the best.”

A more sober statement on a department letterhead said: “This is a judgment that is on the side of the poor. The understanding and the emphasis by the highest court of the land that there should be no disruption in the disbursement of social grants is of utmost importance to the department.”

In reality, all parties before the court had agreed that at as a minimum, the court-ordered solution must ensure that grant payments were not interrupted.

At issue was whether or not the agency had run a regular and fair process. It had not, the court found.

Asked by Talk Radio 702 host John Robbie if this was “a big defeat for Sassa”, the agency’s CEO, Virginia Petersen, was undaunted: “No, it isn’t a defeat. I think the thing that would have worried me [is if] it wasn’t legal. ‘Constitutional invalidity’ means there were infractions in the process that required correction.”

These infractions, according to the court, were twofold. The first was that Sassa failed properly to interrogate the role of CPS’s purported empowerment partners.

Froneman was scathing: “It is difficult to think of a more fundamentally mandatory and material condition prescribed by the constitutional and legislative procurement framework than objectively determined empowerment credentials.”

Sassa’s second infraction was its 11th-hour notice to bidders, which stipulated the requirement of the provision of biometric verification technology for payments. In earlier bid documents, it was a preference.

Only CPS included it in its bid. Froneman found that the notice had “knocked AllPay out of contention”, making the process entirely uncompetitive.

Oliphant and Petersen raised another straw effigy: corruption, and the lack of any finding on this.

Oliphant, for example, told her Twitter followers that the judgment specified “no finding of fraud or corruption”. In fact, the court concluded no such thing.

Throughout 2012, there were various reports and allegations of possible tender malfeasance. AllPay presented some of them to the high court, but ultimately it backed down, focusing instead on the strong evidence of tender irregularity.

For that reason, the constitutional court did not deliberate on the issue, save for rejecting AllPay’s last-ditch attempt to introduce hearsay evidence early this year.

But in the US, where CPS’s parent company, Net 1 UEPS, is listed, the Securities and Exchange Commission and department of justice are still investigating, while the company faces two class action suits from US investors who claim it “failed to disclose that [its] practices to secure contracts in South Africa were in violation of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act”.

Public protector Thuli Madonsela’s office confirmed this week that it is also still investigating alleged bribery, and South African campaign group Corruption Watch said it will ask the police to investigate graft allegations and is considering the option of launching a private criminal prosecution. — (c) 2014 Mail & Guardian

- Visit the Mail & Guardian Online, the smart news source