The pain, it seems, is not over for former Nokia workers as their new employer, Microsoft, prepares to cut its workforce by a massive 18 000. Microsoft has not announced where all of these cuts will come from, but 12 500 are expected to be from the newly acquired Nokia mobile business, which added an extra 25 000 staff this year to swell Microsoft’s staff numbers to 127 000.

![]()

It is not surprising that Microsoft would want to reduce its staff numbers. In a simple comparison of productivity of net revenue per staff between Microsoft and other technology leaders like Google and Apple, Microsoft was lagging even before it took on the extra Nokia staff. At 127 000 staff, profitability would have taken a big hit.

The layoffs are expected to cost Microsoft between US$1,1bn and $1,6bn over the next year in pre-tax charges, which makes the Nokia purchase even more expensive.

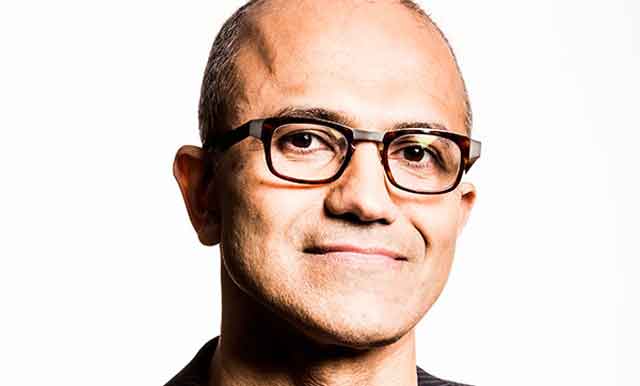

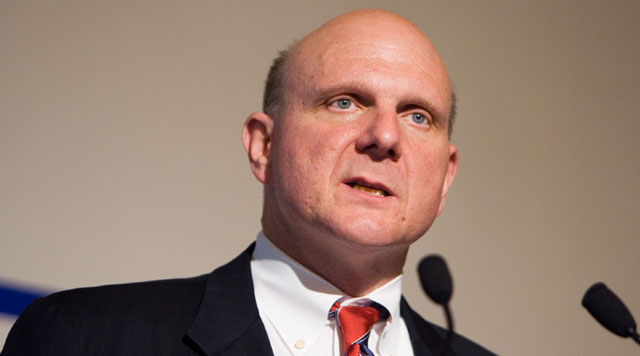

Recently, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella sent an e-mail to Microsoft staff announcing the new direction for the company. No longer would it be a simple “devices and services” company but it would become a “productivity and platform company for the mobile-first and cloud-first world”. It was no secret that former CEO Steve Balmer completely misread the iPhone’s potential and consequently consigned Microsoft’s role in the mobile market to that of an extra. Microsoft, however, has always believed in the mythology that even though it comes to a market late, it can always catch up through sheer will and the declaration that it is suddenly all about devices and services. This was certainly true when Microsoft held a monopoly in the PC market, but it is not the case in markets for which the company no longer has any influence.

Nadella is now doing what most new CEOs do: declaring a new vision. His is all about productivity. This may guide Microsoft into deciding what it doesn’t want to be doing, but unfortunately says very little about what it can do in a market in which it has no presence.

The massive cuts possibly signal that Nadella has no confidence that Microsoft will be able to make something of the mobile phone business it bought for $7,2bn. This wouldn’t be the first time that Microsoft has written off a massive purchase. In 2012, it wrote off most of the $6,2bn it spent on online advertising company aQuantive.

Nokia’s mobile phone business was already struggling before Microsoft bought it and, with the layoffs and change of direction, it seems clear that this is unlikely to change.

As part of the re-definition of Microsoft, it seems that some of the staff cuts will come from the no-longer-core Xbox division. At one point, Microsoft used the Xbox as the spearhead in the fight for the living room. Again, the company viewed the battle to be about PCs. Prior to the Xbox, Microsoft had developed Windows Media Centre with the view that people would have a PC in their living room and this would replace all other types of media devices.

What happened, however, was that people didn’t want PCs in their living rooms and opted instead for smart TVs and a plethora of small and inexpensive media players such as Apple TV and Google Chromecast. If they wanted to surf the Web at the same time, they used their tablet and/or their mobile phone.

As far as the Xbox went, this was never going to make it out of the gamer of the family’s bedroom. It was certainly never going to make it to be the centrepiece of the living room.

However Microsoft decides to “tweak” or restate its business, its fundamental challenge is that it has no real presence in the mobile market. As Apple and Google continue to eat away at the dominance of Windows on the PC, even Microsoft’s two principal cash cows, Windows and Office, are at risk. If mobile defines our future productivity, Nadella’s vision for the company seems unrealistic and it is hard to see a future where Microsoft continues to play anything other than a legacy role.

- David Glance is director of innovation at the faculty of arts and director of the Centre for Software Practice at the University of Western Australia

- This article was originally published on The Conversation