Competition has broken out among telecommunications operators in South Africa as a result of an open-access policy intervention, being the prices which operators pay to access customers on other networks: the call termination rate.

Competition has broken out among telecommunications operators in South Africa as a result of an open-access policy intervention, being the prices which operators pay to access customers on other networks: the call termination rate.

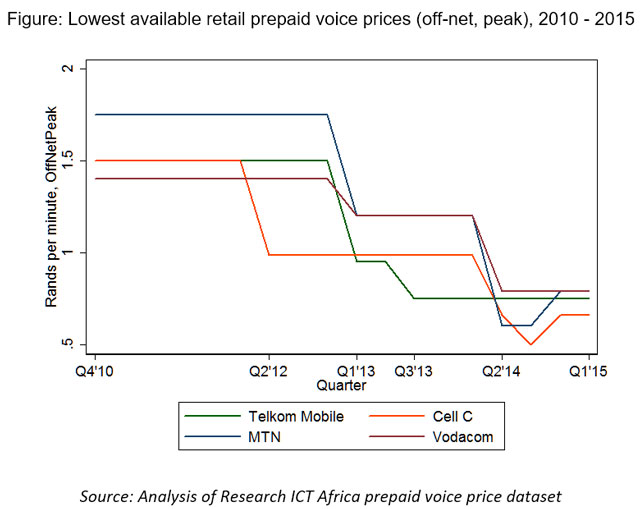

Prepaid mobile voice prices, for example, have declined from R1,50/minute (and more) in 2010 to between 60c and 80c/minute in 2015, according to Research ICT Africa data (see figure below).

This is a consequence of communications regulator Icasa’s call termination rate intervention that began in 2010, which saw peak call termination rates drop for incumbents MTN and Vodacom from R1,25/minute in 2009 to 16c/minute in 2015. The question for South Africa is therefore not whether open-access policies work, it is how best to go about implementing them.

According to recent Centre for Competition, Regulation and Economic Development (CCRED) research, to be debated this week at a public platform, the call termination open-access intervention by Icasa also played an important role in Cell C’s recent growth and market success.

According to recent Centre for Competition, Regulation and Economic Development (CCRED) research, to be debated this week at a public platform, the call termination open-access intervention by Icasa also played an important role in Cell C’s recent growth and market success.

It is important to note that Cell C and Telkom Mobile have played an important role in driving down retail prices. Cell C, for example, was the first to lower prices, in the second quarter 2012, followed later and to a lesser extent by MTN and Vodacom. Telkom Mobile’s later price reductions, particularly in 2013, also appear to have had a significant effect.

In respect of fixed lines, network sharing has also been an important source of success. The same CCRED research provides details on how Dark Fibre Africa’s open-access network has seen considerable growth. Other examples are Vumatel and Fibrehoods’ open-access networks.

A key question is the extent to which these innovative fibre-optic broadband providers are going to be able to extend their networks beyond high-income communities. An exciting possible development in this area is the use of Telkom’s Openserve wholesale offering, which Vumatel is reportedly in talks about.

Spectrum open-access network

The government’s view on open access in the mobile sector seems to be that some sort of wholesale spectrum and infrastructure entity would provide access on a wholesale basis, which MTN has raised concerns about. This seems to be based on similar examples in Rwanda, Mexico and Russia. Leaving aside any criticisms of those policies in those countries, there are few reasons to solve South Africa’s competition problems through a dramatic, untested intervention of this nature. Rather, South Africa should apply tried and tested policy measures to fix South Africa’s competition problems.

In the first instance, it is unlikely that Telkom Mobile and Cell C will roll out full coverage networks, at least not to the same extent that MTN and Vodacom have. This is because of the significant infrastructure costs involved, and the trend in various countries towards infrastructure sharing and network consolidation.

Rather than build a fifth network, the government ought to ensure that access to MTN and Vodacom’s networks are provided on reasonable terms. This includes access to site infrastructure, national roaming services and access to mobile virtual network operator providers.

While the mobile operators (including MTN and Vodacom) already share their sites to some degree, Icasa could do more to ensure that such site sharing is on reasonable terms.

Furthermore, while Telkom Mobile roams on the MTN network and Cell C roams on Vodacom’s network, care should be taken to ensure that these roaming arrangements are not impeding the growth of the challenger networks.

MTN and Vodacom have, historically at least, been reluctant to offer MVNO services on their network. MTN’s recent announcement to allow MVNOs is encouraging. Again, the terms of those arrangements should be assessed, and the government might consider a policy framework that imposes MVNO access on Vodacom.

Rather than hoarding spectrum in a single government entity, spectrum might be assigned to new entrants through Icasa’s auction process.

Smile, for example, has indicated that it would like to operate a wireless network in South Africa. A small proportion of valuable frequency division duplex, and all of the time division duplex, in the currently available 2,3GHz and 2,6GHz bands, and the digital dividend bands at 700MHz and 800MHz, might be reserved for such new entrants.

Similarly, there are a number of small, community-based wireless network operators, particularly in smaller towns and cities, that would benefit from licence-free spectrum, particularly using TV white spaces, which Icasa has been considering making rules for, for some time.

There are therefore a range of traditional, relatively uncontroversial policies that have been implemented in many countries that would improve competition in the mobile sector, without resorting to an expensive wholesale network, which has little prospect for commercial success.

Open-access fixed-line policies

While the government has something of a plan for mobile networks, very little is being done in respect of fixed-line networks.

Although Telkom’s Openserve initiative is welcome, it may not be enough to drive down costs, and ultimately prices, of fixed line networks.

In more than 30 countries (developed and developing), open-access network policies, in the form of local-loop unbundling (LLU), have been implemented. While the weaknesses of copper are regularly cited as a reason for not implementing LLU in South Africa, there are a variety of other forms of fixed line unbundling that form part of LLU and that are of significant importance to new fibre-optic broadband providers.

These include access to Telkom’s ducts and poles, at reasonable prices, an idea that has been implemented by Ofcom in the UK, for example. These would significantly lower the costs of fibre optic deployment in South Africa.

Rapid deployment rules and reducing the costs of approvals

A further important barrier to entry identified by the CCRED research is in respect of approvals by various government entities required to roll out network infrastructure, both mobile and fixed. Delays in approvals mean delays in the expansion of particularly smaller networks, which entrenches the market power of incumbents.

The government’s draft policy in this regard, although welcome, ought to be finalised if the benefits of competition are to be realised among operators in South Africa.

Conclusion

In summary, open-access policies in South Africa have worked very well for consumers in the past. The call termination rate intervention resulted in dramatically lower voice prices for consumers, and aided the expansion of Cell C into the market.

The government’s plans for an untested open-access mobile infrastructure-based operator, however, need to be compared with tried and tested open-access policies implemented in many countries, including rules for roaming, MVNO access and site access together with better enforcement powers and greater independence for Icasa.

Open-access policies should also be considered for Telkom’s Openserve network.

Finally, the government should prioritise finalising rules that would allow for the rapid deployment of networks, which benefit particularly entry by challenger operators, and therefore consumers through lower prices.

- Ryan Hawthorne and Genna Robb are both senior research fellows at the Centre for Competition, Regulation and Economic Development at the University of Johannesburg. Robb is also the manager of competition economics at DNA Economics and Hawthorne is an economist at Acacia Economics