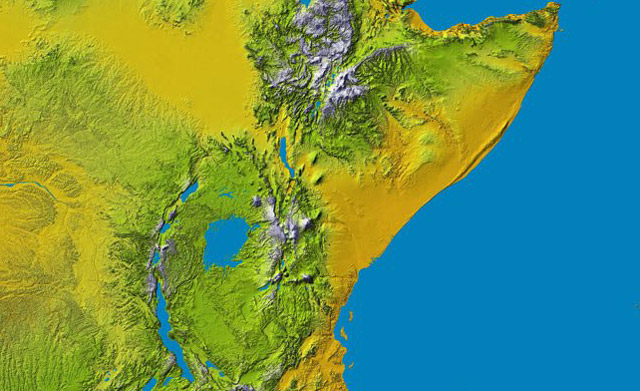

The excitement over the potentially transformative effects of the Internet in low-income countries is nowhere more evident than in East Africa — the last major populated region of the world to gain a wired connection to the Internet.

Before 2009, there wasn’t a single fibre-optic cable connecting the region to the rest of the world. After hundreds of millions of dollars of investment, cables were laid to connect the region to the global network. Prices for Internet access went down, speeds went up, and the number of Internet users in the region skyrocketed.

Politicians, journalists and academics all argued that better connectivity would lead to a blossoming of economic, social and political activity — and a lot of influential people in the region made grand statements. For instance, former Kenyan president Mwai Kibai stated:

I am gratified to be with you today at an event of truly historic proportions. The landing of this fibre-optic undersea cable project in Mombasa is one of the landmark projects in Kenya’s national development story.

Indeed some have compared this to the completion of the Kenya-Uganda railway more than a century ago. This comparison is not far-fetched, because while the economies of the last century were driven by railway connections, the economies of today are largely driven by Internet.

The president of Rwanda, Paul Kagame, also spoke about the revolutionary potentials of these changes in connectivity. He claimed:

In Africa, we have missed both the agricultural and industrial revolutions and in Rwanda we are determined to take full advantage of the digital revolution. This revolution is summed up by the fact that it no longer is of utmost importance where you are but rather what you can do — this is of great benefit to traditionally marginalised regions and geographically isolated populations.

As many who have studied politics have long since noted, proclamations like these can have an important impact: they frame how scarce resources can be spent and legitimise actions in certain areas while excusing inaction in others.

Because the Internet is so frequently talked about in revolutionary terms, colleagues Casper Andersen and Laura Mann and I decided to compare in a paper the many hopes, expectations and fears written about the Internet with those from another transformational moment in East Africa’s history: the construction of the Uganda Railway.

The railway was built from 1896 to 1903 between Mombasa and Lake Victoria, connecting parts of East Africa to each other and the region to the wider world. There were strong views at the time of what this could bring. The journalist and explorer Henry Morten Stanley claimed:

I seemed to see in a vision what was to happen in the years to come. I saw steamers trailing their dark smoke over the waters of the lake; I saw passengers arriving and disembarking; I saw the natives of the east making blood brotherhood with the natives of the west. And I seemed to hear the sound of church bells ringing at great distance afar off.

A young Winston Churchill waxed lyrical on the new railway:

What a road it is! Everything is apple-pie order. The track is smoothed and weeded and ballasted as if it were London and North-Western. Every telegraph post has its number; every mile, every hundred yards, every change of gradient, has its mark … Here and there, at intervals which will become shorter every year, are plantations of rubber, fibre and cotton, the beginnings of those inexhaustible supplies which will one day meet the yet unmeasured demand of Europe for those indispensable commodities… In brief, one slender thread of scientific civilisation, of order, authority, and arrangement, drawn across the primeval chaos of the world.

After a full analysis of the historical and contemporary texts, we can make two key points.

The hopes and fears people hold about changes to how they connect with other people and places are surprisingly similar across generations. But there are notable differences between these two moments, a century apart.

The arrival of the railway revolved around the use of technology to integrate an empire and open up new lands to imperial ambitions. By framing the arrival of the railway as allowing the core to extend its dominion over the periphery, what was said and written at the time served to legitimise the extension of colonialism.

The arrival of fibre-optic cables, however, presents a different story. Instead of a world of shrinking space between the core and periphery, it tends to lean more on the idea of a “global village”. The need to connect everyone to the global economy overrides concepts of self-sufficiency, local economies, or trade outside the global marketplace.

These visions matter because they leave little room for alternatives. Just as dominant narratives around the arrival of the railway presented a worldview amenable to colonialism, contemporary dominant narratives offer a convenient justification of globalised capitalism and neo-liberalism.

How people imagine they are connected to the world matters. They shape how we make sense of the world and ultimately what steps we take to reshape the world. We should therefore look to the past, and not just the future, when we examine the effects of the changing ways in which we are connected.

Mark Graham is associate professor, Oxford Internet Institute, at the University of Oxford

Mark Graham is associate professor, Oxford Internet Institute, at the University of Oxford- This article was originally published on The Conversation