A financial crisis confronting South Africa’s state power utility has become a national debt problem.

A financial crisis confronting South Africa’s state power utility has become a national debt problem.

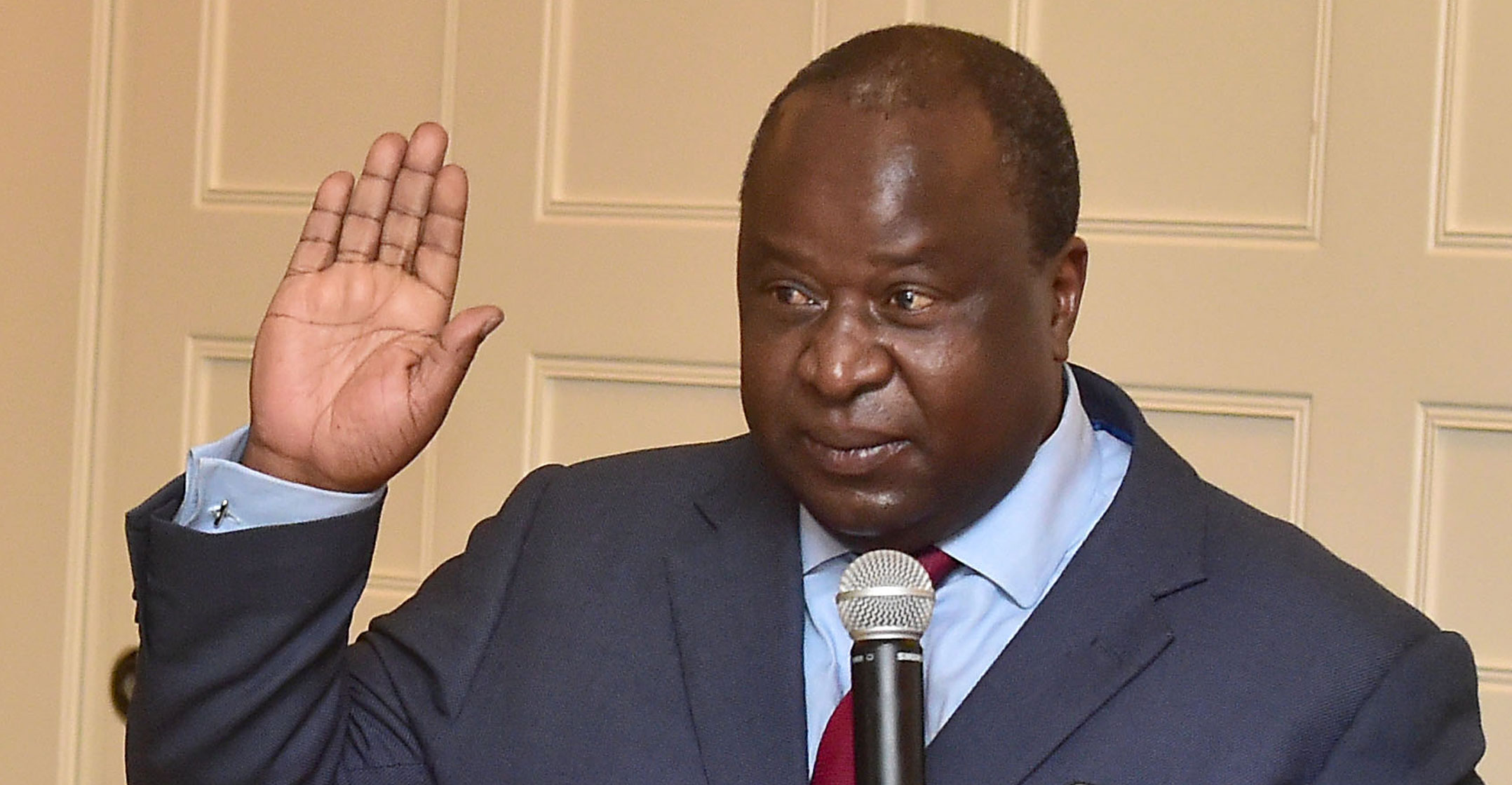

Finance minister Tito Mboweni on Tuesday unveiled a second multibillion-rand bailout for Eskom. within five months, aid that may force the cash-strapped government to increase borrowing and taxes. That could in turn trigger a credit-rating downgrade and massive outflow of funds, raise the cost of new debt and stymie efforts to revive the moribund economy.

“At the end of the day, short-term capital injections into Eskom don’t address its balance sheet issues and there’s still no sign of a turnaround strategy,” said Jeffrey Schultz, senior economist at BNP Paribas South Africa. “It is what it is — South Africa has to take in on the chin.”

The R59-billion cash injection into Eskom over the next two years should help the utility keep a lid on its R440-billion debt pile and remain solvent, especially when combined with an earlier three-year, R69-billion bailout. But the money probably won’t be enough to wean it off state support: the utility’s old plants are losing money and struggling to produce enough power to meet demand.

Further details of a government task team turnaround plan, which includes splitting it into generation, transmission and distribution units under a state holding company, remain under wraps. The board also has to name a new CEO to replace Phakamani Hadebe, who will leave at the end of the month, while the appointment of a chief restructuring officer is imminent.

‘Extremely serious’

“We are facing an extremely serious financial situation,” Mboweni told MPs in Cape Town. “Eskom is not financially sustainable based on its current high levels of debt and its inability to generate sufficient revenue to meet its operational and capital obligations, which exposes the entity to high levels of liquidity and balance sheet risks.”

The rand weakened after Mboweni’s comments, declining as much as 0.6% to R13.95 against the dollar on Tuesday before paring losses, while yields on government bonds due in 2030 climbed the most in six weeks. Eskom produces about 95% of South Africa’s power, and the government has said it’s too big and important to fail.

The difficulty the government faces in coming up with the money for Eskom may be compounded by tax revenue falling short of what was anticipated at the time of the February budget. The fiscal deficit for this year was projected to be the highest in a decade before the extra funding was accounted for and public debt was projected to stabilise at 60.2% of GDP in 2023/2024.

Morgan Stanley analyst Andrea Masia sees the budget gap widening to about 6.4% of GDP in the current fiscal year and 6.6% in 2020/2021 as a result of the additional bailout. The February budget projected a gap of 4.5% and 4.3% for the two years respectively, but the country’s growth prospects have deteriorated significantly since then.

“Additional support for Eskom comes at the price of a wider fiscal deficit and larger debt burden, exacerbating an already challenging fiscal backdrop,” Masia said in a report. “In the end, it’s the taxpayer that foots the bill.”

Eskom’s woes and the knock-on effect they have had on South Africa’s finances have soured Aberdeen Asset Management’s appetite for the country’s debt.

“We just have our risk chips elsewhere,” said Edwin Gutierrez, the London-based money manager’s head of emerging market sovereign debt. “It’s a bit too early to call it a sovereign-debt crisis. But yes, debt continues to march in the wrong way.”

About 62% of Eskom’s total debt is guaranteed by South Africa’s government. Moody’s Investors Service, the only major ratings company that still classifies South Africa as investment grade, includes all that debt in its assessment of the nation’s fiscal situation on the grounds that the utility can’t service its obligations without state backing.

Downgrades

South Africa’s ability to avoid ratings downgrades will depend on it formulating a well-coordinated rescue for Eskom that will address its financial and operational deficiencies, according to Schultz of BNP Paribas.

“I cannot see how rating agencies can turn a blind eye to something like this given the extent of the deterioration we’re going to see in debt and deficit metrics,” he said. — Reported by Prinesha Naidoo, Colleen Goko and Mike Cohen, with assistance from Paul Burkhardt, Paul Vecchiatto, Rene Vollgraaff and Robert Brand, (c) 2019 Bloomberg LP