Two years ago, Oppo and Vivo couldn’t crack the top five in China’s smartphone market. Now they outrank everyone after elbowing Apple aside, thanks to people like Cheng Xiaoning.

Cheng runs a thriving electronics store in the rural town of Miaoxia, tapping into her WeChat social media account to promote the brands that pay the biggest commission, and in her case that’s Oppo and Vivo. While such payments start at about 40 yuan (US$6; R84), they escalate for more expensive handsets and reach almost 200 yuan for Oppo’s high-end smartphones.

“That’s why I like to introduce the Oppo R9 Plus to potential customers,” she said. “Business has been perfect, actually never been better.”

Cheng and tens of thousands of like-minded boosters form the vanguard of the pair’s charge against Apple and Samsung Electronics. Working with the local stores that dominate sales in China’s far-flung provinces, Oppo and Vivo came out of nowhere to upend the industry order and squeeze out former local darling Xiaomi. Their labels graced one out of every three smartphones sold within China in the third quarter, while the iPhone’s market share at 7% stood at its lowest in almost three years.

Oppo and Vivo trace their origins to reclusive billionaire Duan Yong Ping and employ similar strategies. That includes harnessing the spending power of rural customers away from top-tier cities such as Beijing and Shanghai. It’s where Apple’s vulnerable given the iPhone’s lofty price tag. They eschewed e-commerce to instead court the stores where three-quarters of smartphone sales take place. Apple has been more reluctant to relinquish the retail experience to local free-agents, who sometimes charge brands for in-store displays and posters.

“Oppo and Vivo are willing to share their profit with local sales. The reward was an extremely active and loyal nationwide sales network,” said Jin Di, an IDC analyst based in Beijing. While they declined to detail their subsidy program, she estimates the two were the top spenders in the past year. “They’re doing something different — they do local marketing.”

It’s unclear how Apple can reclaim lost ground in the interim. Previous attempts to drift down-market fizzled as local users shunned seemingly inferior devices

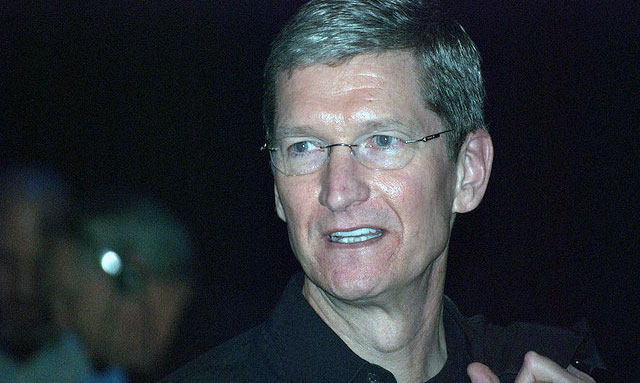

China had for years driven Apple’s and Samsung’s growth. The US company generated almost $59bn of sales from the region in fiscal 2015, which was more than double the level just two years earlier. During that time its shares surged more than 60%. At its peak, Greater China yielded almost 30% of its revenue and Apple was neck-and-neck with Xiaomi for the mantle of market leader as users clamoured for the larger iPhone 6 models. Even as the domestic economy began to sputter, CEO Tim Cook spent a good chunk of an earnings call last year talking up the country’s promise, saying Apple’s investing there “for the decades ahead”.

Then the country’s slowdown and regulatory tangles took their toll. Authorities intervened, blocking iTunes Movies and iBooks, ending a period of near-unimpeded growth in the country. But perhaps most crucial was the ascendancy of cheaper but just-as-good local alternatives. Oppo and Vivo’s gains have come mainly at the expense of lower-tier names thus far, but if they climb further into the premium segment, the US company will need an answer. Some think the 10th anniversary iPhone due in 2017 could deliver.

“Apple needs to offer something cutting edge to appeal to maturing Chinese smartphone users,” Counterpoint Research director Neil Shah wrote. Oppo and Vivo can use the time until then to cement their positions, he said.

Together, Oppo and Vivo shipped about 40m smartphones in the third quarter, about 34% of devices sold in the world’s biggest market, according to IDC. In 2012, their combined share was about 2,5%. iPhone shipments plunged more than a third to 8,2m during the period — less than half of Vivo’s. Samsung, which once led the market, now settles for roughly 5%, according to Counterpoint.

As Apple has faltered in China, Cook has stepped up his courtship of decision-makers. He visited the country several times this year, unveiled plans for research centers in Beijing and Shenzhen, and invested $1bn in Uber rival Didi Chuxing. Cook said on his last earnings call he remains confident of a return to growth this quarter.

Samsung declined to comment for this story, while Apple didn’t respond to requests for comment.

It’s unclear how Apple can reclaim lost ground in the interim. Previous attempts to drift down-market — with the iPhone 5c and SE, for instance — fizzled as local users shunned seemingly inferior devices. Apple doesn’t run a vibrant online social community for users the way some of its local rivals do. And competing on price will jeopardise the industry’s fattest profit margins.

While Xiaomi shot to international prominence with flash online promotions, that success has been concentrated in densely packed cities

Oppo and Vivo pack high-end specs into a phone that sells for a fraction of its rival’s in China, where iPhone 7s start at 5 388 yuan ($784; R11 000). Consider the Oppo R9 plus: for 2 999 yuan, buyers get an aluminum body, 6-inch display, 16-megapixel camera and a battery that claims 19 hours of calls, photo and Web browsing. Vivo’s high-end Xplay6, with a price tag of 4 498 yuan, also undercuts Apple.

“Both companies invested heavily in marketing,” said Nicole Peng, Asia Pacific research director at consultancy Canalys. Oppo and Vivo have a strong grip on the middle market for phones from $200 to $500, she said. “Their offline channel strategy paid off.”

The man who’s clobbering Apple started out low on the tech spectrum. Duan made his fortune selling DVD players, telephones and game consoles similar to Nintendo’s. Bubugao Communication Equipment Co, the parent of Vivo, emerged from a restructuring in 1999 that split his company. The billionaire later teamed with long-time colleague Tony Chen and others to found what came to be known as Guangdong Oppo Electronics Co.

While Duan has kept a low profile since moving to the US in 2001, he occasionally makes his way into the spotlight. In 2006, he bid a then-record $620 100 to have lunch with Warren Buffett. Oppo’s first smartphone came in 2011, when it unveiled a device with a BlackBerry-like keyboard. The same year, Bubugao created the business that would become Vivo.

Today, Vivo touts its cameras and Oppo focuses on rapid-charging and battery life. But their offline strategies remain the same: mobilising tens of thousands of private shop owners. Oppo said it sells its products through roughly 240 000 privately owned stores as of June — six times the global count of McDonald’s. Vivo manages about half that, said Jin. Oppo, which doesn’t disclose sales figures, said about 90% of its phones were sold offline.

While Xiaomi shot to international prominence with flash online promotions, that success has been concentrated in densely packed cities. That doesn’t work so well in the countryside, where novice buyers want advice and demonstrations. By cultivating a physical network, Oppo and Vivo are building a platform difficult to replicate in the short run.

Apple, in contrast, has fewer than 40 stores across the mainland, most of which are in large cities. While its retail network is lauded for helping weave an aura of exclusivity and chic around its higher-priced gadgets, Chinese consumers — particularly in smaller, poorer cities — value access to someone local who can work out kinks. That sort of after-sales support is in itself a powerful marketing tool, IDC’s Jin said.

For now, neither Oppo nor Vivo appear overly concerned with the world’s most valuable company. Their executives say they’ll stick to their winning strategies, while exploring ways to keep pushing the smartphone envelope.

“We have to keep our minds clear in the fast-changing market,” said Allen Wu, Oppo’s vice-president in charge of sales. “All we need to do is to keep our heads down and make the correct moves.”

To Vivo, that means targeting younger users with higher-performance devices. “Camera and music will be our key focuses in the future. We are seeing greater customer expectations out of these two areas,” company vice-president Ni Xudong said.

That message resonates with the likes of Chen Siyu, an accountant who uses her Vivo phone at least four hours a day to chat with friends, watch videos and apply for jobs.

“I chose Vivo because of its design and photographing capability,” said the 26-year-old who lives in the town of Pu’tian in Fujian. “It is not expensive and doesn’t slow down after longtime use like many Android phones do.” — (c) 2016 Bloomberg LP