The universe still holds many mysteries. The SA engineers and scientists working at bringing the world’s largest radio telescope, the Square Kilometre Array (SKA), to SA are hoping to solve some of those mysteries and shed light on how the galaxies, stars and planets came into being.

Not only are these engineers and scientists breaking ground in the field of radio astronomy, they are developing some of the world’s most advanced technology while they prepare the country to host the €1,5bn (about R14,6bn) telescope. Construction of the telescope is set to begin in 2016 and the telescope should be fully operational by 2024.

Bernie Fanaroff, director of SA’s bid to host the SKA, says the project was birthed in the early 1990s when astronomers started talking about the “next big thing” in their field.

They wanted to be able to observe neutral hydrogen from the birth of stars a few hundred million years after the Big Bang. Neutral hydrogen consists of a single proton orbited by a single electron and is found in the vicinity of stars that are being born.

To do this, scientists need to build a gigantic radio telescope with a collecting area of at least one square kilometre. This telescope also needs to have a high dynamic range, or the ability to see extremely faint objects in the presence of very bright ones.

And they want to do all of this as cost effectively as possible.

Fanaroff says SA became involved in the project in 2005 when it submitted its expression of interest to the SKA committee to become one of the countries bidding to host the telescope.

The country entered the ring alongside the US, China, Canada, Argentina and Australia.

“Our submission surprised many people because Australia was widely tipped to be the country to host SKA. People were mostly surprised by the quality of our submission,” he says.

It was at that point that SA became a serious contender to host the project, and was short-listed alongside Australia.

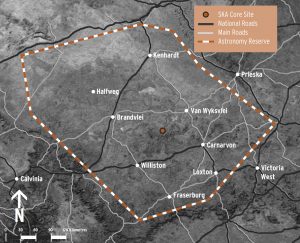

SA proposed a desolate site in the Karoo, near the towns of Carnarvon and Williston in the Northern Cape. Crucially, the earmarked site has few cellphone towers or radio broadcasts that could cause unwanted interference.

Keeping the radio waves clean is a must if the project is to receive the purest radio waves from the furthest reaches of the universe.

The idea is that the SKA site will be linked to a powerful computing facility in Cape Town via fibre-optic lines. The facility, if it is built, will have computing capacity of hundreds of teraflops per second.

Southern African countries, including Namibia, Botswana, Mozambique, Zambia, Mauritius, Madagascar, Kenya and Ghana, will host outlying stations that connect to the main site in the Karoo, says Fanaroff.

Fanaroff and SA’s SKA team are putting together a report detailing interference at the proposed site. This will be one of the last submissions to the international SKA committee that will then make a decision on which country will host the telescope.

The committee is expected to make its final decision by next year.

In the meantime, SA has not been sitting idly by waiting for a decision. It has started building and testing technology that could be used for the SKA.

To do this, the department of science & technology has agreed to help fund the development of MeerKat, a precursor to the SKA. On its own, MeerKat will be one of the largest and most powerful telescopes in the world.

The MeerKat project has already produced some of the most cutting-edge engineering in the field of radio astronomy, and SA engineers are creating low-cost technologies that are up to par with SKA standards.

Recently, the team scored a breakthrough in the development of the dishes that will receive the radio signals from space, successfully building and testing a prototype composite dish. Composites are naturally occurring materials that are engineered together to form tightly woven fibres.

Using composites to build the dishes is a breakthrough for the project because traditionally dishes were made of heavy metal panels that had to be transported one at a time to a site to be put together to work.

“With composite, we can build the entire dish, without the base, on site and simply lift it up and place it on the bases as needed,” says Fanaroff.

Not only is this a lightweight solution, it is a cheaper way of building the dishes — and keeping costs down is requirement of the SKA. They can also be built much faster than the traditional structures.

The next step for the team was to build another six of these dishes and string them together to build a receiver, called an interferometer, the portion of the project called Kat-7.

According to Fanaroff, the dishes designed in SA for MeerKat will also have less scatter, or noise, that interferes with the readings they receive, a structure that is closer to the final design specifications of the SKA dishes. “This again puts us in good stead to win the bid,” he says.

MeerKat will comprise 64 of these dishes and should be fully functional within four or five years.

Even though the project is not nearly finished, astronomers from around the world are already proposing they be chosen as the first scientists to use MeerKat for their projects.

“More than 43 000 hours, or about five years, of observing time has already been allocated to astronomers who have applied for research time on our telescope,” says Fanaroff.

One of the first projects for MeerKat will be examining the timing of pulsars, which can be used to develop highly accurate clocks or detect gravitational radiation. Scientists hope to test the limits of Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity.

Another MeerKat project will look at the early hydrogen of the universe, but will not look as far back as the SKA will be able to once it’s built.

Not only is MeerKat in demand, but engineers that have worked on the project have also started to become well known and respected in the global scientific community, says Fanaroff.

One of the developments that boosted the fame of SA’s engineers was the development of Roach (reconfigurable open architecture computing hardware) motherboards.

The hardware development was started at Berkley University and has been fine-tuned by SA engineers specifically for the telescope projects. The boards allow easy upgrades when technology changes need to take place in the telescope arrays.

The boards are also designed to manage extremely fast input and output through their buses (subsystems that transfer data between computer components) and can be programmed using firmware to perform specific functions.

Fanaroff says SA engineers have also been working on wireless technologies, fast data transport, large networks of sensors, software radios and imaging algorithms.

He says if SA wins the bid to host the SKA, it would help put the country on the scientific map and boost development in science and astronomy in SA, which in turn would elevate the economy. “This must be a long-term vision of prosperity for the country,” he says. — Candice Jones, TechCentral

- Subscribe to our free daily newsletter

- Follow us on Twitter or on Facebook