[By Justin Spratt] Large sums of money are available to technology start-ups in SA. But there are almost no technology start-ups getting funded.

This is a big problem for the country, both socially and economically, as it strives to lift its long-term growth trajectory. Foreign direct investment and portfolio investment flows will never achieve this alone. Strong growth in new businesses is paramount for growth and social upliftment.

Start-ups in the technology sector offer the fastest growth opportunities, simply because of faster economies of scale and usually require lower capital investment, making it the perfect industry to target start-ups. So it’s worrying that so few are being funded.

There are two schools of thought as to what the problem might be.

The first is that the capital available is too risk-averse, that money is not available early enough in the start-up process.

The second reason given is that SA start-ups don’t have sufficient skill in product development and management. Theories on why this is the case range from corporate SA sucking up all the talent, to culture, and to lack of training in these disciplines in tertiary institutions.

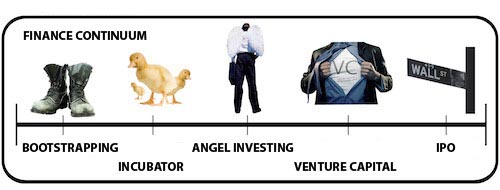

Before we unpack each of these theories, we should take stock of the evolutionary stages that start-ups go through. They usually start by “bootstrapping” themselves. This means self-financing or borrowing money from friends and family.

More often than not, start-ups usually get to a point where they need external, structured capital. It’s at this point they usually require seed funding. Depending on how well they have bootstrapped themselves, this could be through angel investment or the more structured venture capital.

Angel funding is usually provided by successful businesspeople who lend money on less stringent and more favourable terms to new entrepreneurs — Johann Rupert is a notable example in SA.

More sophisticated types of capital come in the structured forms known as venture capital. Within VC, there are “tranches” of money provided, depending on the “round” of investment. Each round is designed to give more scale, in turn to take the startup closer to the money making “exit”– often a stock market listing.

So if we plot out the types of financing for start-ups, we get what I call the “financing continuum”.

With capital being too risk-averse, it means that money is only available closer to the “exit” stages. In SA, there is very little demand at this late stage from new businesses. Conversely, there is almost no source of capital at the seed (early) stage. Clearly this gap is problematic as we try and foster a culture of entrepreneurship to obtain the growth and upliftment needed.

The supply of start-up businesses for latter-stage investment is scarce because of the lack of skills to develop slick “productisation” (ability to price and market products) and go-to-market strategies.

In the words of the talented Vinny Lingham, founder of Yola.com, “product management skills in SA start-ups are almost non-existent”. He says people with these skills tend to be drawn into the corporate world by big salaries and then don’t bring those skills into the start-up ecosystem.

Andrea Bohmert, Managing Partner from HP-Ventures, a venture capital fund with money from SAP co-founder Hasso Plattner, expresses a similar concern. She sees many great ideas from smart people in SA but they lack key elements of being able to bring those ideas to market.

As a result, and in order to offer a solution, there is an increasingly popular form of investment financing that focuses on nurturing these skills. They’re called incubators. Notable examples include 20FourLabs (part of the MIH group); Vodacom Labs; Internet Solutions’ ISLabs (internal and external projects); and, to some extent, Stellenbosch’s Media Lab.

These incubators provide almost no financing but rather focus on mentoring, providing strategic input, and opening doors to opportunities. The paragon examples internationally of this nascent form of funding are Paul Graham’s Y-Combinator and Guy Kawasaki’s Garage Technologies.

It’s early days yet, but if Y-Combinator’s success in America is anything to go by — 10% companies already funded with only 20% failing — it looks like the incubator model will fill the gap in the start-up financing ecosystem. — Justin Spratt

- Spratt is co-founder of ISLabs