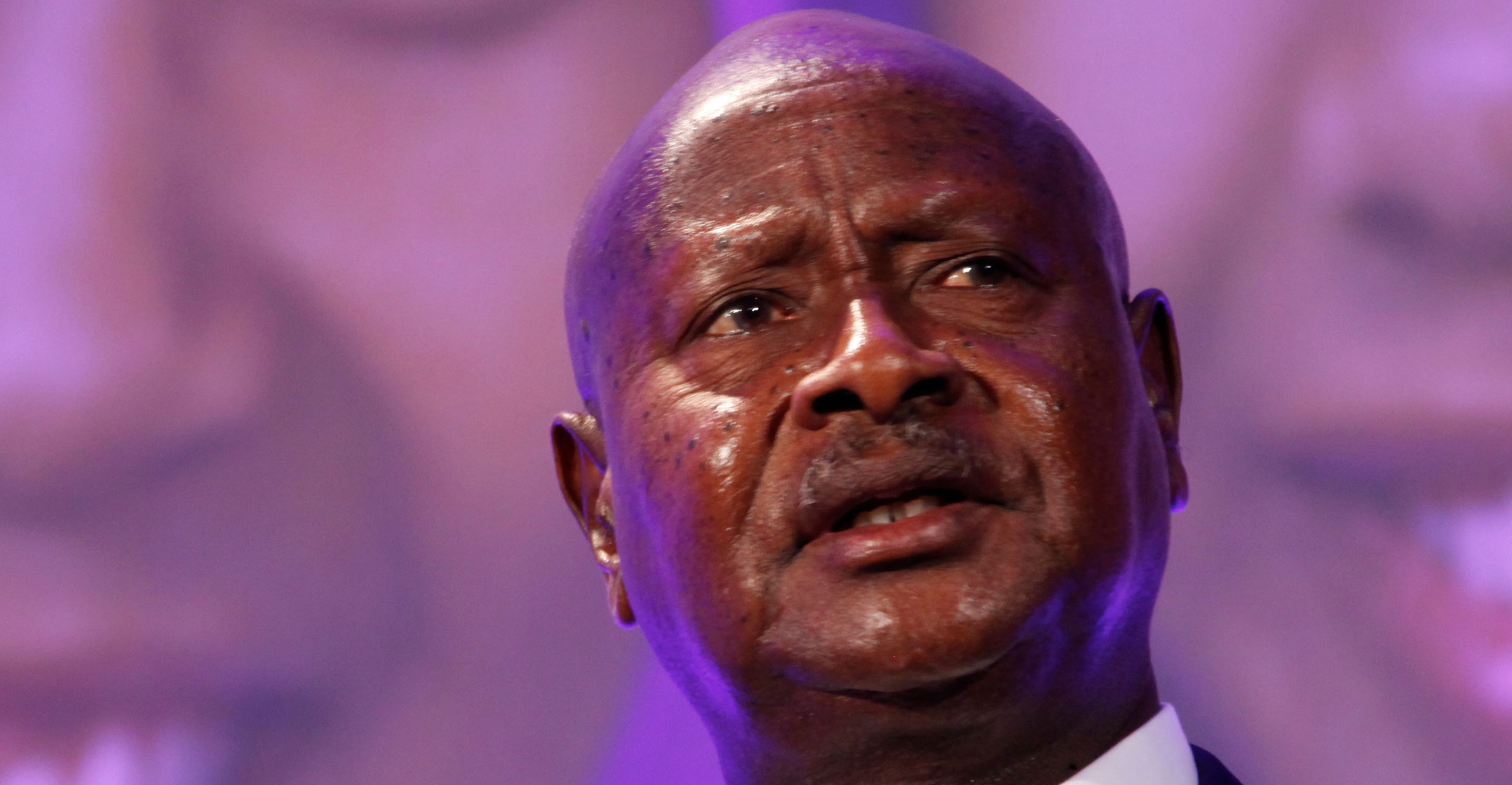

Uganda’s shutdown of social media services in January, right before a disputed election handed President Yoweri Museveni a sixth term, dealt a devastating blow to rice trader Elizabeth Nagunda: Her sales slowed to a near halt.

“Before I would advertise, market my products on Facebook, WhatsApp, and even get customer orders” via those platforms, she said in an interview in Kampala, the capital. “I can’t run any more adverts online. Even if I do, there are no people to view them.”

Facebook and Google are spending billions trying to get more people online in Africa, but the Internet giants are now facing a backlash from governments worried about social media platforms being used to remove them from power.

These platforms, including Twitter, gave opposition politicians access to previously unreachable audiences and have been used to organise protests — most notably during the Arab Spring that toppled leaders from Tunisia to Egypt.

Now governments in sub-Saharan Africa are increasingly ordering Internet service providers to shut their gateways or throttle data traffic when confronted with dissent or the threat of electoral defeat.

Facebook, Twitter and other companies have pushed back, condemning the disruptions and blocking accounts they allege are being used to undermine democracy — actions that further raised the authorities’ ire and led to several outright bans on their services. Access Now and the #KeepItOn Coalition, which campaign for an end to Internet shutdowns, documented 20 intentional disruptions in a dozen African nations last year.

Worst violators

Ethiopia was among the worst violators of online freedom in 2020, imposing at least four outages in a bid to contain ethnic unrest and restrict the flow of information during a conflict in its northern Tigray region.

More curbs have been introduced in 2021. The latest was in Senegal, where the government imposed an outage earlier this month after the arrest of an opposition leader triggered the most violent demonstrations in years.

“Not only do Internet shutdowns interfere with the rights to access information, freedom of expression and other fundamental freedoms, they are used in attempts to hide egregious human rights violations,” Access Now said in a report published on 3 March.

Tech executives have long preached about offering their services to the estimated three billion people who remain offline, about 700 million of them in Africa. Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg has argued that connectivity is a basic human right.

Early endeavours to get more people online seemed more fanciful than serious. Facebook tried to build a gigantic drone to provide high-altitude connectivity but grounded the Aquila project in 2018 after only two test flights, the first of which ended in what was described as a “structural failure”. Google — using a project called Loon — attempted something similar with helium-filled balloons sailing into the stratosphere, scrapping it in 2021 after the unit failed to develop a viable business model.

Early endeavours to get more people online seemed more fanciful than serious. Facebook tried to build a gigantic drone to provide high-altitude connectivity but grounded the Aquila project in 2018 after only two test flights, the first of which ended in what was described as a “structural failure”. Google — using a project called Loon — attempted something similar with helium-filled balloons sailing into the stratosphere, scrapping it in 2021 after the unit failed to develop a viable business model.

Now the tech companies are taking the opposite approach, driven in part by a desire to win over a vast swathe of new users. Facebook and some of the world’s largest telecommunications carriers are spending about R15-billion building a subsea Internet cable that will connect Europe to the Middle East and 16 African countries. Google has announced its own subsea cable connecting Europe to Africa, using a route down the west coast.

For now, companies have limited scope to counter Internet shutdowns. Social media platforms are also trapped between attempting to be seen to counter misinformation and working with local governments to provide Internet access.

Telecoms companies say they’ll lose their operating licences if they ignore government orders to halt or restrict Internet access. Even so, they’ve faced accusations that they are overly accommodating towards repressive regimes and complicit in denying people access to an essential public good.

“Companies should definitely be taking a tougher stance,” said Nic Cheeseman, a professor of democracy at the University of Birmingham. “If a company wants to depict itself as being about freedom of information — as most telecoms companies do — then they must defend media freedom, even in cases where it might hurt their business interests to do so.”

‘Compliant’

MTN Group, Africa’s largest wireless carrier by sales, responded to queries by referring to a statement published on its website that states: “Our response to digital human rights is underpinned by a sound policy and due-diligence framework. Our approach is consistent with internationally recognised principles, while ensuring that MTN remains compliant with the terms of our various jurisdictional legal obligations and licence conditions.”

Rival Vodacom Group said it seeks to balance its responsibility to respect its customers’ right to privacy and freedom of expression against its legal obligation to respond to the authorities’ lawful demands, while safeguarding its employees. Airtel Africa and Orange, which also have wireless operations on the continent, declined to comment.

Shutdowns “are hugely harmful, and undermine the public conversation and the rights of people to make their voices heard”, Twitter said in an e-mailed response. “The long-term result of this could be an Internet that is less open, less free and less empowering for all.”

“Even temporary disruptions of Internet services have tremendous, negative human rights, economic and social consequences,” Facebook said in a written response to questions.

“Even temporary disruptions of Internet services have tremendous, negative human rights, economic and social consequences,” Facebook said in a written response to questions.

It’s questionable whether governments derive any benefit from trying to stop their citizens from communicating: Research published in 2019 by Jan Rydzak, an associate director at Stanford University’s Global Digital Policy Incubator, showed social media curbs tended to fuel rather than reduce violence; and Internet shutdowns in Algeria and Sudan did nothing to quell protests — and may in fact have stoked outrage and accelerated their leaders’ downfalls.

Besides stifling democracy and free speech in the world’s poorest continent, the disruptions have had far-reaching economic consequences, hindering business activity, curbing tax revenue and deterring foreign investment. Top10VPN, a UK-based digital privacy and security research group, estimates that shutdowns cost the sub-Saharan African region an estimated US$237.4-million last year.

In Ethiopia, the communications blackout prevented accurate reporting on the conflict in Tigray and fettered aid agencies trying to help tens of thousands of displaced people. Phone connections have been restored to major towns and cities, but data services remain suspended.

The absence of a vibrant, independent mainstream media in many African nations makes a lack of access to online content all the more problematic.

“News about us and news about the values that we stand for does not feature on local radio or local TV,” Bobi Wine, a Ugandan pop star-turned-politician who alleges that the vote he lost to Museveni was rigged, said in an interview with Johannesburg radio station 702. “Social media is our only platform to express ourselves and communicate the raw reality of what is happening in Uganda.” — Reported by Loni Prinsloo and Michael Cohen, (c) 2021 Bloomberg LP