With thousands of users from around the world and around 70PB (that’s petabytes) of data handled on a daily basis, the European Organisation for Nuclear Research (Cern) has a surprisingly simple technology requirement.

You won’t find large supercomputers with thousands of specialised cores or massive data centres in large warehouses. Instead, Cern’s Openlab chief technology officer Sverre Jarp has employed a Google-like technology architecture to keep the place running.

Jarp says the nature of the work done at Cern doesn’t require the resources that many other scientific institutions need, because the research can be done at the pace set by the scientists.

The organisation has had to move with the times, coming from a Risc-based architecture, to now running a full network on PC-based machines connected to balance the resources needed by thousands of scientists across the world.

“With millions of events being analysed by many scientists it has worked out well to spread the workload over the many computers,” he says.

However, the accuracy of the data analysed is not always at 100%. However, Jarp says the scientists are aware of the reliability and work around it. “Google is much the same, you may have to click again to get a page to load, but you never question Google’s reliability. Sometimes, our scientists have to simply click again,” he says.

When the project first started, Jarp says the organisation predicted it would receive about 15PB of data a year. However, this has skyrocketed to 70PB.

Jarp has not built a modern data centre to cope with the masses of data. Instead, Cern uses a decidedly 1990s technology to store data: tape.

Jarp says using tape may sound archaic, but it’s still much cheaper than other storage options available today.

Cern has a warehouse of tapes that are automatically retrieved by a robot if requested by a scientist. The data is then transferred to DVD, which offers faster read-write access than tape.

“We can easily tell if data hasn’t been accessed in a long time, and those tapes get moved into another segment of the warehouse for permanent storage,” he says.

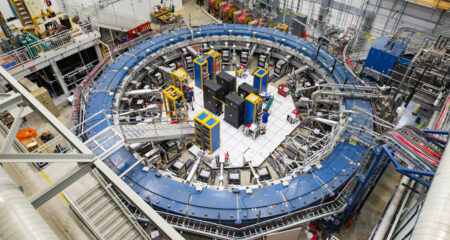

The Cern network has both internal and external access points. It connects about 140 sites worldwide in a grid. It supports 250 000 CPU cores.

Securing a global network is not easy, says Jarp. “We have to keep it as open as possible, with so many different devices accessing the services. But we have to make sure that it is as secure as possible.”

As with all networks, users are the biggest threat. “As one of the largest scientific experiments, Cern is very visible, so we have strict policies and dedicated staff who make sure those policies are adhered to,” he says.

It has already come under fire in the media following accusations that a hacker had been using the vast network as a starting point for committing several crimes. (Jarp says the stories weren’t true.)

The security policies also help protect the property of scientists, many of whom have developed their own applications that govern their experiments and research.

Cern’s IT department has even developed its own distribution (version) of Linux, which it provides to everyone using the network.

Jarp says Cern is also keen to explore future options in cloud computing (where IT services are moved onto central network resources). However, any move in this direction would take place in the long term.

In the meantime, Jarp says the technology it has now gives scientists more than they need to make science’s greatest discoveries yet. — Candice Jones, TechCentral, Switzerland

- Subscribe to our free daily newsletter

- Follow us on Twitter or on Facebook