“This is the way the world ends,” writes TS Eliot in The Hollow Men, his masterful poem about death and dying.

“This is the way the world ends

Not with a bang but a whimper.”

I’m sitting in the load shedding-induced silence, thinking about this remarkable poem with its nod to “Mistah Kurtz”, a character from Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness who is an empty tyrant. Kurtz, the avaricious, whose goodness was eaten by ambition, power and greed. Kurtz whose intent in Africa was all about “humanising, improving, instructing”.

If you’re living on the grid, there’s a lot of time to think these days. When the fridge stops humming and when the ambience of the computer screen dulls. There is no grand announcement to this interruption to life. At best the “whimper” of a mobile signal offers warning, but often only after the electricity is off.

I can gnash and howl and join that great South African fraternity of whingers — the social media moan-bags, the digital outrage machine with its daily machinations. The problem with carping is that even though it’s a “doing word”, it’s a verb that yields little return. Yes, there’s some catharsis, but it doesn’t turn the power back on. Human hot air has also yet to be effectively harnessed for national power grids.

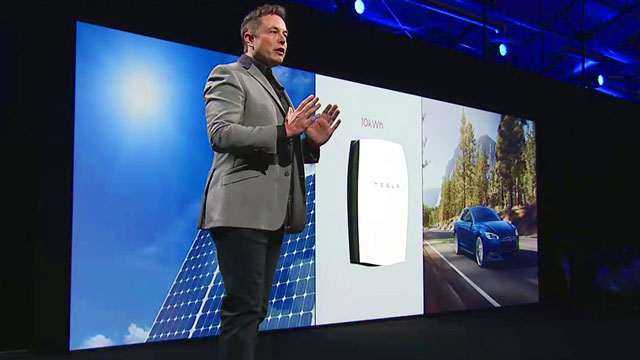

What about “Captain Media” Elon Musk’s new battery? The South African-born Musk — who founded PayPal — announced a new product called the Powerwall on 30 April.

This is a rechargeable lithium-ion battery designed for domestic use that is mounted on a wall and stores electricity. “This is the same kind of lithium-ion battery that is used in cellphones and other electronic devices,” Chris Yelland tells me. A chartered engineer who holds a BSc in electrical engineering, Yelland is an energy expert who publishes in the power sector.

Yelland says the electric vehicles market has driven demand for large battery packs, but obviously Musk went one step further by creating batteries for home and commercial use. “Mr Musk has opened a new plant in Nevada that is breathtakingly massive in its size, scale and its ambition,” says Yelland, who predicts that time will see more innovation, development, cost reduction and scale in this sector. But innovation in the field of batteries is largely dictated by physics.

In simple terms, batteries are a means of storing electrical energy, and the chemistry associated with this is fairly complex. The big question, says Yelland, is how to increase a battery’s energy density. In other words the quest is to put more energy into smaller units and to make these batteries last longer, and to do this affordably. “If you can get much longer life, you are changing the game economically. The batteries launched by Mr Musk have a life of 10 years.” That’s double the current standard.

“The physical properties of material are not something that can be easily changed,” says Yelland. “Process technology changes come intermittently and in a much slower fashion.” The development of batteries has taken decades and consumers are only now enjoying the fruits of this labour.

The problem with the Powerwall as a local solution is threefold. “It is being presented as an ‘off grid’ solution,” says Yelland, who cautions: “We have to separate the hype from the reality. If you look at the reality, ‘off grid’ is a stretch. The Powerwall sells for R40 000/unit and on its own is not a solution for getting off the grid.”

A typical middle class house — the type of family that might be able to afford a Powerwall — draws about 30kWh a day. A Powerwall stores about 10kwh. If you want to live off grid using a Powerwall, you’d need to install solar panels, which means your battery will need recharging three times a day.

But, there there’s only about eight hours of sunlight a day. This means you’ll need more batteries – about two [or even better], three. Before you know it your off grid system will cost you close to R150 000!

That’s if you can even get a Powerwall. A few days after Musk announced the launch of the battery, it was sold out until mid-2016. Never mind, there are local alternatives. Htxt.africa reports that NetshieldSA offers a locally designed inverter system that can take one off grid affordably. Freedom Won also offers a battery that can be “charged from the grid to supplement power during load shedding” or paired with solar panels for an off-grid solution.

But the smartest fix I’ve yet seen was created by an electrician who hails from the small fishing hamlet of Ocean View near Fish Hoek, on the Cape’s southern peninsula. Rastafarian Ricardo Fortune waited for Eskom to connect his home for years, and eventually got so sick and tired of waiting that he made his own plan. Fortune uses a wind turbine that harnesses False Bay’s abundant wind for energy, and supplements this with solar panels. He also has a bank of car batteries that power his low-level energy requirement devices like lights, mobile phones and a computer.

Caveat lector — this is not a quick and easy DIY home solution. When you’re playing with electricity and batteries (which contain chemicals), you have to know what you’re doing. Fortune is an electrician which is why this solution works for him. When you start building banks of lead-acid batteries there’s the danger of combustion and corrosion, which is why expertise is essential.

But the moral of Fortune’s story is safe and accessible. While the “hollow men” focus almost exclusively on consolidating their own power and care little about service delivery, South Africans, like Fortune, must make a plan. We need to stop being whiny and dependent, and start becoming more independent of Eskom.

The second, longer term strategy is focusing on how to disrupt the power of the “hollow men” who rule in the name of extreme self-interest and greed, and not for the greater good of this country. That’s the real load this country must shed.

- This piece was first published on Moneyweb and is republished here with permission