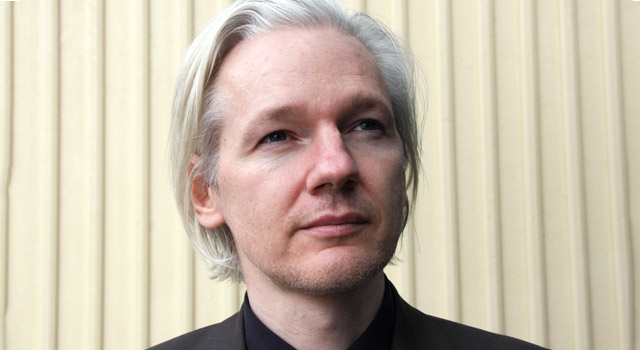

The United Nations’ working group on arbitrary detention has decided that Julian Assange is being “arbitrarily held” by a concert of powers — so how might this curious situation play out?

The working group finds that Assange is not only entitled to his freedom of movement, but that he has a right to compensation.

This is, of course, a major PR victory for Assange. And whatever one thinks of the underlying story, the UN report is a fascinating analysis of the susceptibility of national criminal processes (including on extradition) to international legal review.

So far, there have been no winners in this unique diplomatic quagmire, which has been stagnant since Assange claimed diplomatic asylum in 2012. Both Sweden and the UK have nothing to gain by becoming vicariously liable for his “arbitrary detention”, even if only in the court of international public opinion. Expect angry voices on both sides to raise the matter at this year’s UN general assembly.

In a sense, the finding of the UN panel is binding mostly as a matter of international moral authority. Should the UK and Sweden choose to ignore the ruling, it could compromise their ability to boldly denounce other perhaps more repressive states in the future — particularly on the basis of any finding by the same UN panel. Both states have appeared over the years at the UN as champions of human rights and dissident cases, and neither has any urge to lose that cachet.

So what now? Despite the chagrin of the British and Swedish governments, there are a few ways forward.

Breaking the deadlock

Swedish officers could visit the Ecuadorian embassy to question Assange and take depositions. Maybe even an extraterritorial trial by an extraordinary Swedish court within the embassy can be arranged. Nothing is impossible in the world of diplomacy.

Assange’s lawyers have urged the charges to be dropped, although this is unlikely to happen before he is formally questioned. Either way, keeping him under what’s now deemed to be “arbitrary constructive detention” will only increase his political martyrdom.

The continuance of diplomatic asylum within the territory of a state hostile towards the accused is always very tricky. The course of events and end-game scenarios tend towards the bizarre. US marines blasted hard rock music at deafening levels to flush Manuel Noriega out of the Vatican’s embassy in Panama. Peruvian politician Haya De la Torre was holed up in an embassy for at least three years while Colombia and Peru fought over the matter at the international court of justice.

And then there was Umaru Dikko. Dikko, a Nigerian politician who fled a huge corruption investigation at home in 1984, was kidnapped on the streets of London. He was then drugged and crated in what was described as “diplomatic baggage” for export back to Nigeria, accompanied by Israeli agents and doctors tasked with keeping him alive in the crate.

It need not come to that. The panel’s conclusions could possibly inject some pragmatism into the whole affair. Assange could capitulate and walk out into the waiting hands of the UK law and be extradited, or perhaps an English court could refuse to allow his extradition based on the UN ruling. Both Assange and Ecuador could drop their claims for compensation for housing and inconveniences.

Now that the decision, however contentious, has been committed to paper and made public, all the concerned parties might finally have an impetus to find the necessary political will to reach some workable compromise to melt this excruciatingly slow-moving diplomatic glacier.

In the meantime, perhaps agents at British, Swedish and American airports should watch out for unusually large diplomatic baggage.![]()

- Gbenga Oduntan is senior lecturer in international law, University of Kent

- This article was originally published on The Conversation