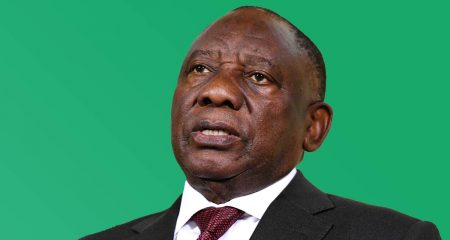

Just last month, President Cyril Ramaphosa assented to the Cybercrimes Bill to bring into law the Cybercrimes Act. The legislation creates offences which have a bearing on cybercrime, including the distribution or disclosure of data messages that are harmful. However, although it has been signed into law, it remains without a commencement date.

In terms of the Cybercrimes Act, messages that threaten destruction to an individual’s person or property are criminal offences. Specifically, section 14 of the act provides that: “Any person who discloses, by means of an electronic communications service, a data message to a person, group of persons or the general public with the intention to incite (a) the causing of any damage to property belonging to; or (b) violence against, a person or a group of persons, is guilty of an offence.”

As a society, we have noticed the recent spreading of malicious and harmful messages. The question should be asked – to what extent has this contributed to the current dissonance?

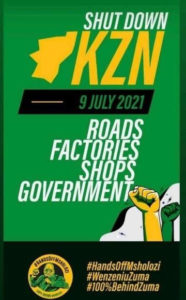

As an example, in a series of posts dated 9 July, a Twitter account shared content which encouraged the then-imminent violent protest action with the hashtags #ShutdownSA and #FreeJacobZuma. One such post contains an image of a poster which reads as follows:

We have to consider whether messages of this nature constitute incitement and, if so, incitement to do what?

Platforms such as Twitter would constitute electronic communications services and the posts shared therein would constitute data messages in terms of the Cybercrimes Act. An additional question to be answered to satisfy the definitional elements of section 14 of the act is whether there is an intention to incite damage to property or violence against a person or groups of people.

Case law

In Economic Freedom Fighters and another vs minister of justice & correctional services and another (CCT201/19) (2020) ZACC 25, the constitutional court held that the test for incitement is whether speech or conduct incites another or others to commit serious offences either at common law or against a statute or statutory regulation. This raises the question of what is the meaning of “serious”. The constitutional court gave examples of crimes such as murder, rape, armed robbery, fraud and corruption, and further stated that other crimes which are deemed evil by their very nature would constitute serious offences. Schedules 1, 2 (parts II and III) and 5 to 8 of the Criminal Procedure Act may also provide further guidance in that they list offences that seem to qualify as serious. These include public violence and breaking and entering with intent to commit an offence, all of which we have seen in the recent unrest.

Consequently, tweets reflecting messages as reflected above, could very likely be interpreted to fall within the ambit of section 14 of the Cybercrimes Act.

Social turns antisocial

Although legislation such as the Cybercrimes Act is not the answer to curing the root cause of the unrest, it can still serve to assist our security and policing cluster in effectively intercepting and, where necessary, prosecuting such offences. It can introduce various efficiencies in the investigation and prosecution of cybercrimes such as mandated cooperation with law enforcement by electronic communications service providers, the establishment of a designated “point of contact” (meant to be a special, cybercrime-dedicated structure within the police) and a requirement to train police members in aspects relating to the detection, prevention and investigation of cybercrime.

With such measures, which enable increased human and operational capacity, individuals who are acting as the catalysts for ongoing violence and unrest can be traced and held to account for their actions. However, given the lack of a commencement date, the Cybercrimes Act remains an unavailable tool in the armoury of our law enforcement.

Undoubtedly, when social media turns antisocial — in that it is misused to mobilise to commit acts of violence — we ought to be armoured with law to deal with it decisively.

- Ahmore Burger-Smidt is director and head of data privacy and the cybercrime practice at Werksmans Attorneys