Analysts have long criticised Telkom since its entry into the mobile market in October 2010, which hasn’t come cheap.

Analysts have long criticised Telkom since its entry into the mobile market in October 2010, which hasn’t come cheap.

In the six years since Telkom’s mobile business launched (originally under the 8ta brand), it racked up a total of R7-billion in earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation (Ebitda) losses.

The first few years were indeed rocky. In the 2011 financial year, when it launched, then-CEO Nombulelo Moholi was adamant that, while “pushed out” from the original business case, Ebitda break-even would be in FY2014. It took three years longer.

However, in the past three financial years, it has generated positive Ebitda of approximately R5-billion. By the end of this financial year (March 2020), the unit will have clawed back all of the historical losses. Turning a profit, though, is only one piece of the equation.

Telkom today is a very different business from a decade ago (even five years ago):

- The mobile unit is at scale;

- The mistaken foray into Africa (Multi-Links and iWayAfrica) has long been exited;

- The acquisition of BCX in 2016 helped grow revenue at the expense of margins (the business’s margins are structurally lower than Telkom’s);

- The wholesale unit has been separated into Openserve; and

- The traditional fixed-line business is in deep trouble.

Just how much trouble is clear from financial results for the past two years.

Losses

The consumer business (“Telkom” as we know it) reported an Ebitda loss of R146-million in the 2018 financial year. Revenue from the fixed-line unit was R9.3-billion then, with mobile at R7.2-billion. In the year to 31 March 2019, the bottom line had swung to an Ebitda profit of R1.03-billion. Mobile is now a significantly bigger business than fixed, with revenue of R10.9-billion versus R8.3-billion (it’s important to note that all enterprise business has been folded into BCX). A R1-billion revenue decline in the consumer fixed-line business is startling. While it didn’t disclose the mobile unit’s Ebitda profit in FY2019 (this writer estimates it at between R2.7-billion and R3-billion), it is all but certain this ensured the swing to profit.

Without mobile, Telkom’s consumer business would be deeply loss-making (some of this relates to the separation of Openserve in 2015 — it has higher margins than the customer-facing units, perhaps artificially so).

Mobile is a business in rude health. At the end of March, it had 9.68 million active customers, with nearly 1.9 million of those on post-paid. Blended average revenue per user is R99.90/month.

Aside from the Ebitda losses, building out a mobile network has come at a real cost: over R14-billion in capital expenditure as at 31 March 2019. This equates to 25% of the group’s total capex (R57.2-billion) over the last nine financial years.

CEO Sipho Maseko has been smart, however. The group doesn’t see its mast and tower portfolio as passive. It is managing this, together with its property portfolio, in a separate business, Gyro. In the past year, mast and tower revenue is up 35% to R930-million, primarily from its nearly 1 400 multi-tenanted towers.

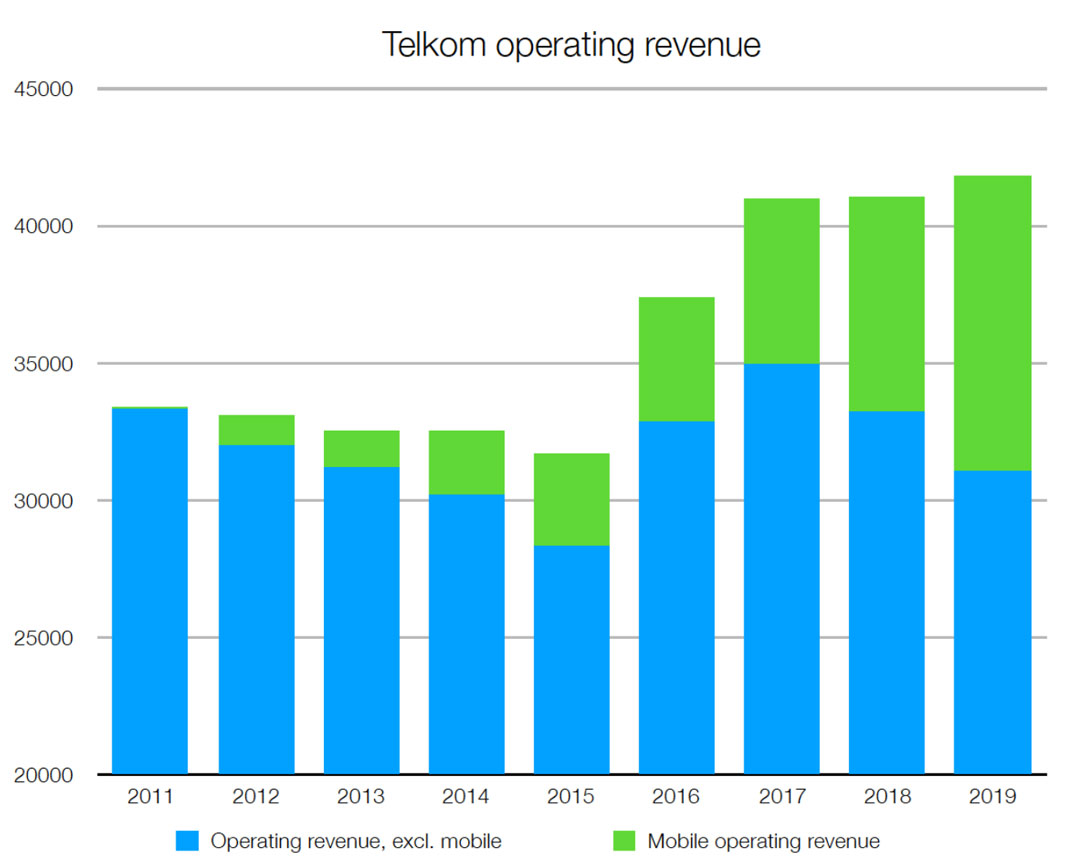

Without mobile, Telkom would, quite simply, be a declining business. More than all group revenue growth in recent years has come from mobile. In other words, mobile revenue growth has more than offset declines across the rest of the group.

Excluding eliminations, the changes in operating revenue in the past year look like this:

- Openserve: R585-million decline

- Consumer fixed line: R1.013-billion decline

- Consumer mobile: R3.726-billion growth

- BCX: R683-million decline

- Gyro: R225-million growth

The group may well have bought BCX regardless of whether it entered mobile. But even with that additional turnover (over R9-billion, excluding enterprise fixed line which has been shifted into BCX), group operating revenue would be lower today than it was in FY2011, were it not for mobile.

The picture looks even worse on an Ebitda basis. Total Ebitda is up R2.1-billion since FY2011 (to R11.3-billion), but would be down approximately R1.6-billion over that same period were it not for mobile. Today, mobile is 26% of group revenue and estimated at slightly less as a percentage of group Ebitda. Soon these numbers will be closer to 33%.

Critics may argue that Telkom had no option but to build out a mobile business. But it did have choices: a potential merger with MTN was floated at one point (it’s hard to see whether communications regulator Icasa or competition authorities would’ve allowed it), and it has considered buying Cell C numerous times over the past decade and a bit. Given the debt load Cell C is labouring under, even after a recapitalisation, it is clear why management simply couldn’t make a Cell C transaction work. Telkom’s mobile business is in significantly better shape than Cell C.

Even with R14-billion and counting in capital expenditure, the decision by former CEO Reuben September (he left Telkom in July 2010) to sell the group’s Vodacom stake in 2008 and enter mobile on its own — which Moholi then implemented — has been more than vindicated.

September and Moholi made many other mistakes when they led Telkom, but they got the most important call right.

- This column was originally published on Moneyweb and is used here with permission