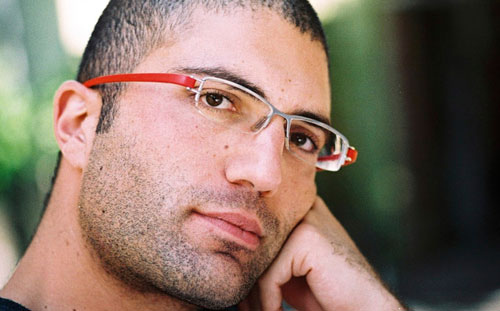

Yossi Hasson, MD of open-source software specialist Synaq, is tall, dark, handsome and gifted. Which means my first instinct is to dislike him. However, Hasson proves to be as friendly as he is talented when I meet with him on a cold weekday afternoon in a Sandton coffee shop.

“From a very young age I knew I wanted to be an entrepreneur or a business owner,” Hasson says when I ask how he got started in the technology industry. “I thought that was the best thing you could do — never mind being a doctor or a firemen or anything else.”

Hasson says he taught himself how to sell stuff when he was young. His father was self-employed, and Hasson saw entrepreneurship as the best way “to control my destiny and make money”.

When he was 11, Hasson started washing cars for money and doing other odd jobs. From there, he roped in his sister and her friends to make key rings for sale in Plettenberg Bay during school holidays. By 15, he was selling medical sports equipment to schools.

“I got my first computer when I was 14, a red Stallion XT. I fell in love with computers and the tech world and the infinite possibilities they presented. I took the machine apart the day I got it, and couldn’t put it back together, but eventually I learnt how to. I got entrenched in technology from there.”

“I got my first computer when I was 14, a red Stallion XT. I fell in love with computers and the tech world and the infinite possibilities they presented. I took the machine apart the day I got it, and couldn’t put it back together, but eventually I learnt how to. I got entrenched in technology from there.”

In his matric year in 2000, Hasson launched a social network for matriculants to post pictures and message one another. At its peak, Matric 2000 had almost 3 000 users. Hasson says that was the turning point for him and he decided that, rather than study, he wanted to get involved in the business world immediately.

Hasson’s business partner, David Jacobson, was a hacker who managed to get his computer confiscated by the police when he was 17, and found himself banned from being online for a year. “I saw him as a guy I needed to get involved with because I wanted the best people. We started chatting after school, but at first nothing came of it.”

After finishing matric, Hasson started a business importing second-hand cellphone parts. After two-and-a-half years he sold the company and became a fundraiser for Habonim Dror, a Jewish community charity organisation, for a year.

“I was still involved in programming, website design and that sort of thing, and I was obsessed with Linux and open-source software,” says Hasson. When Jacobson returned from an extended stay in London in 2004, the two mates began talking about business ventures again.

“Dave had built an anti-spam solution for an Internet service provider in SA,” says Hasson. “It was killing expensive proprietary solutions, and it was open source.” Shortly thereafter, the two decided to start Synaq — at the time intended as a managed Linux service company offering open-source solutions.

Synaq launched on 1 September of that year, with Hasson and Jacobson having raised R1m to start the business. Hasson had been working for an online retailer and had other lucrative offers, but decided he wanted his own business.

Synaq grew as a managed Linux services company, and went on to launch products like Pinpoint SecureMail, the first hosted, cloud-based anti-spam service in SA.

Fast forward to 2011, and Synaq is primarily a cloud service provider. It remains Linux-based, but is no longer a custom Linux support provider. “We changed our strategy to be cloud-focused. That’s where we saw the future, particularly with bandwidth costs coming down, more affordable infrastructure, and a skills set that allows us to build scalable systems,” says Hasson.

Hasson says the change of strategy took 18 months to implement fully, but that it proved to be a good move. “We’ve launched a software development division that’s building global cloud services now, rather than only local ones”.

Synaq is launching another new product soon. “It’s called BrandFu, an e-mail branding and e-mail signature management system. It allows for centralised management with integration into Google Apps,” says Hasson. Synaq plans to market BrandFu globally when it launches in August.

Though this may sound ambitious, Synaq is already home to a number of sizeable clients. Hasson says most of Synaq’s customers are small and medium-sized businesses, but bigger clients include MTN.

“All of their e-mail goes through our servers, it’s checked for spam, we make sure the reputation is good, and so on,” Hasson says. MTN alone accounts for 500m e-mails a month on Synaq’s platform.

Synaq has clearly attracted the right sort of attention. In May, Dimension Data’s Internet Solutions (IS) acquired 50,1% of Synaq. Hasson says that although a controlling stake was one of the conditions of the acquisition “we retain full management control”.

“IS is a very good partner,” says Hasson. “They believe in the management team and what Synaq have done to date. The deal with IS gives us leverage, and in turn we’re seeing where we can help them.”

Hasson says IS has little by way of an open-source competency and that Synaq is helping rectify that. IS, meanwhile, will provide Synaq with the necessary capital to expand its operations.

Despite having foregone tertiary education after school, Hasson now holds an MBA from the Gordon Institute of Business Science. “I was 26 when I applied and had no degree. I got rejected. I appealed the rejection, and sent them a list of the business books I’d read and a proposal based on their curriculum. I also met with the academic director, and managed to get a three-month probation,” says Hasson.

He has no regrets about studying later in life because four years of running Synaq “made the MBA classes more applicable, and I was more keen and more active”.

“I don’t think people should go straight from school to varsity. Going against the mould is probably something shared by most successful people across all industries,” says Hasson. “They went for what they were passionate about and their perseverance made it work. I recommend working for a company for a few years”.

Having been an avowed capitalist since his youth, Hasson says the notion of a community developing software for free, as in the open-source world, intrigued him. “They were so passionate and, even though they worked for free, they could create better software than companies were making. I also saw the business potential of having access to amazing software for free.”

Asked what the largest challenges are for the local IT industry, Hasson says it’s the shortage of skills, of developers in particular. “We need more Shuttleworths, more rock star geeks. Maybe we just need more role models”.

Another problem is a lack of vision by local entrepreneurs. “US start-ups think about global domination, raise funding to do it and aren’t scared to chase a good opportunity, even if they sometimes get it wrong.”

SA start-ups often fail to aim for global success, says Hasson. “Synaq was no exception. At first we thought too small, too local, and about small problems. We’ve learnt the importance of changing that way of thinking.”

Hasson says that for the local IT industry to flourish, South Africans need access to reliable, affordable infrastructure. By way of example, he says Synaq used to host its servers in the UK and that moving their hosting to SA “increased our expenses 400%. There’s no reason that should be the case – for a start-up that’s a massive increase.”

When Hasson isn’t working, he participates in a number of networking groups and events, lectures part-time at the Gordon Institute on entrepreneurship, and plays poker. “I’m also an avid Starcraft player. I’m still a geek at heart. I try and read a lot of nonfiction, too, and I love to travel.” — Craig Wilson, TechCentral

- Top image courtesy of Dan Rosenthal

- Subscribe to our free daily newsletter

- Follow us on Twitter or on Facebook