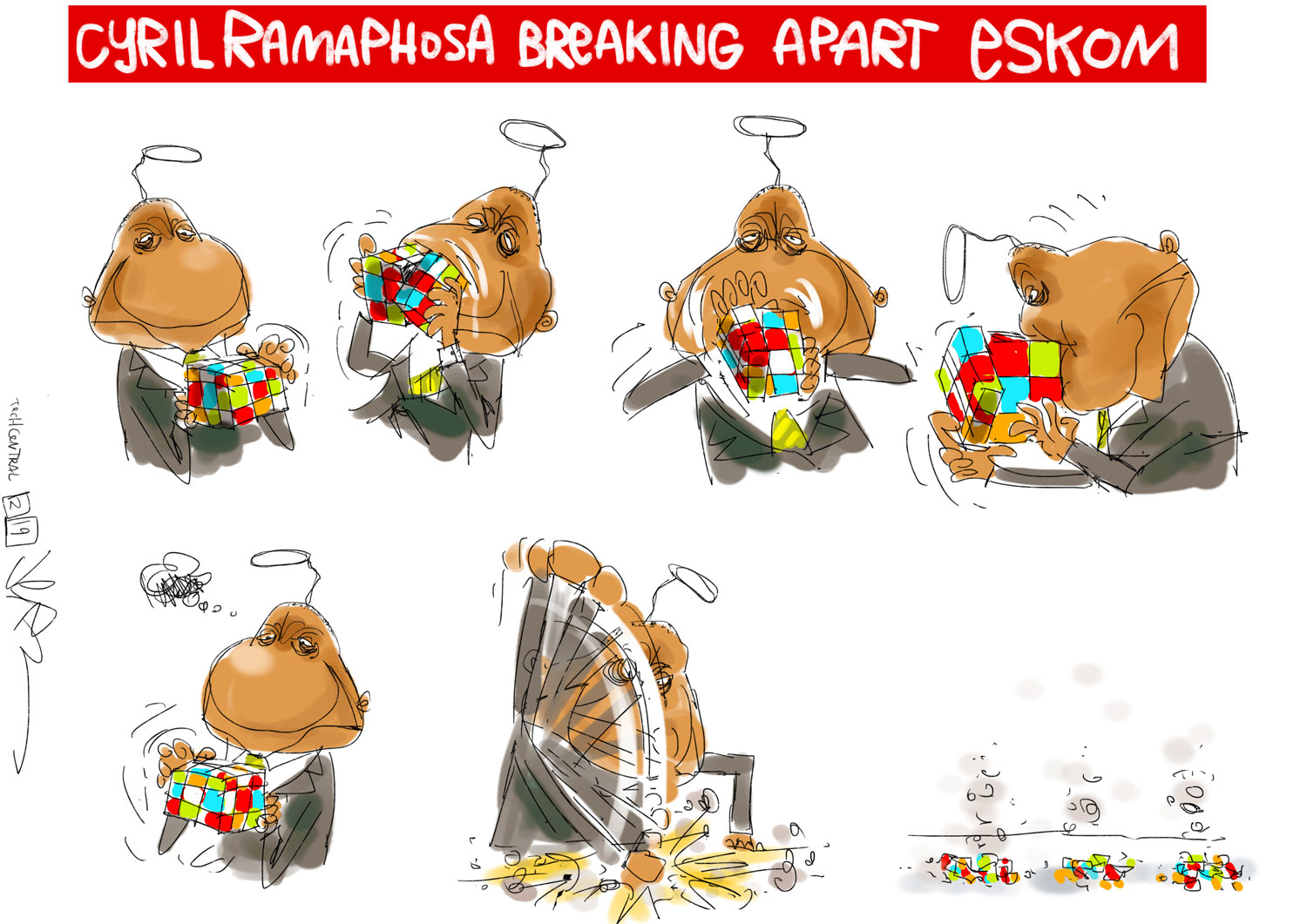

Six months ago, President Cyril Ramaphosa said the country’s indebted power utility would be split in three, it would get new leadership and its debt wouldn’t become a burden on the nation’s finances.

Six months ago, President Cyril Ramaphosa said the country’s indebted power utility would be split in three, it would get new leadership and its debt wouldn’t become a burden on the nation’s finances.

Instead, an initial bailout has been increased by R59-billion, no plan has been announced to restructure the overstaffed company, and the finance minister says government borrowing will surge and taxes may rise. The government has yet to appoint a new CEO and a chief restructuring officer, first promised in a national address by Ramaphosa on 20 June.

“Nothing is happening at any speed,” said Mike Schussler, chief economist at Economists.co.za. “There seem to be too many people pushing back. We have to do structural changes,” such as splitting up the business and privatising assets.

Fixing state-owned Eskom was always going to be difficult. The utility, which has over R440-billion in debt, isn’t selling enough power to cover its costs. Its ageing and inefficient power plants operate on coal and routinely violate emissions standards. The company has been plagued by mismanagement and political manoeuvring, leaving it with a bloated workforce whose shrinkage is bitterly opposed by South Africa’s powerful unions.

Moody’s Investors Service, the only major credit-rating company that still assesses South Africa’s debt as investment grade, said on Thursday that the additional support without an accompanying plan to make the company more sustainable is “credit negative”.

Bond holders and analysts who have met informally with executives from Eskom, officials from national treasury and members of a task team appointed by Ramaphosa to advise on Eskom say they’ve emerged from the meetings confused and with the sense that there is no clear plan. They asked not to be identified as the meetings were private.

Roadshow

The company plans to meet with investors in a non-deal roadshow the week of 5 August, said Ksenia Mishankina, a senior credit analyst at Union Bancaire Privee in London.

Eskom said on Thursday it had started the process of appointing financial advisers “to assist it with the planning phase of the implementation of the government support package. The company didn’t immediately respond to queries about the roadshow or the plan; national treasury declined to comment on the plan.

Many bondholders and analysts do say that the current bailout is enough to keep the wolf from the door for now. That’s reflected in bond prices. So far this year, the yield on Eskom’s 2025 dollar bonds has declined 415 basis points to 5.88%.

“The support seems enough to allow Eskom to have a going concern status and to plug the funding gap for now,” said Tarryn Sankar, an investment analyst at Cape Town-based Futuregrowth, which manages R188.5-billion rand in fixed-income investments. We are “no clearer on where ultimate accountability for returning Eskom to sustainability lies”.

“The support seems enough to allow Eskom to have a going concern status and to plug the funding gap for now,” said Tarryn Sankar, an investment analyst at Cape Town-based Futuregrowth, which manages R188.5-billion rand in fixed-income investments. We are “no clearer on where ultimate accountability for returning Eskom to sustainability lies”.

A number of solutions have been floated. These include decommissioning coal-fired plants early and replacing the generating capacity with renewable energy. That could pave the way to tapping as much as R200-billion of climate change mitigation funding from international agencies. Another proposal is to swap the R90-billion of Eskom debt held by Africa’s biggest fund manager for equity.

“First the CRO is needed, then they need to bed in, then they need to appoint advisors, then they need to formulate a plan, then a chosen plan must be presented to government and receive sign-off and then it must be executed,” Peter Attard Montalto, head of capital markets research at Intellidex, said in a note to clients this month. “This process could take at least six months but likely a year through to execution. This is all before unbundling to occur.”

Even the governments’ drive for more renewable energy is in chaos. On 29 June, trade & industry minister Ebrahim Patel said the government is taking steps to have Eskom produce more solar and wind power. On 15 July, Gwede Mantashe, the energy minister, said in his budget speech in parliament that additional coal power is back on the table.

On 22 July, his department fired Karen Breytenbach, the head of the Independent Power Producer Office,. She had been credited with overseeing R209-billion of investment in 112 renewable energy programmes in South Africa. She said she wasn’t given a reason and had a contract until April next year. Two days later, the department said her contract had expired.

The decision drew a protest from Anton Eberhard, a member of Ramaphosa’s task team on Eskom. “Zero corruption,” he said in a Twitter post. “President @CyrilRamaphosa’s investment drive needs good institutions and people to succeed.”

Overstaffed

Two of South Africa’s biggest unions, the National Union of Mineworkers and the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa, represent the bulk of Eskom’s more than 48 000 workers, a number that the World Bank has said is 66% too high. Both have threatened to bring Eskom to a halt if jobs are cut and in previous wage disputes their members were accused of sabotaging plants and causing power outages. Ramaphosa is a co-founder of the NUM, a union which remains a key political ally of his, while Numa is a foe of the ruling ANC.

“Eskom is a political minefield with many vested interests at play, complicating any potential restructuring and turnaround plan,” said Mauro Longano, a fixed-income portfolio manager at Coronation Asset Management, in an article on the Daily Maverick website on Thursday. “The market will solve the electricity crisis, and the role of Eskom as the sole provider of electricity will diminish. How much more discomfort South Africans will endure before this happens, however, is a question that ultimately only the government can answer.” — Reported by Antony Sguazzin and Colleen Goko, with assistance from Selcuk Gokoluk, Gordon Bell and Rene Vollgraaff, (c) 2019 Bloomberg LP