Warning: this review contains spoilers

Liberal writers have been lining up for the last month and a half to decry American Sniper along comfortable and predictable ideological lines. “Macho Sludge” was the title of an Alternet piece by David Masciotra. Chris Hedges called it “a grotesque hypermasculinity that banishes compassion and pity”. Meanwhile, comedian Bill Maher characterised it as a film “about a psychopath patriot”.

For certain, the film makes a hero out of a killer — Navy Seal sniper Chris Kyle, who was responsible for more deaths than any other sniper in US history. It romanticises his desire to protect fellow soldiers in the US war in Iraq. Perhaps worst of all, it trades on longstanding Western stereotypes of Arabs and Muslims, ranging from inscrutable to untrustworthy to profoundly sadistic.

But straight propaganda rarely makes for compelling entertainment, so the enormous popularity of American Sniper (hauling in a mind-boggling US$306,5m in the US alone so far) suggests that it has resonated far beyond the hardcore group of ultraconservatives these reviewers would expect to embrace the film.

Far from being a film that simply trumpets the superiority of American values and military might, American Sniper depicts white, male vulnerability, along with the tragic costs of war — at least, for Americans.

Ambiguity over violence and its purposes — both at the societal and individual level — is a common theme in the films of American Sniper’s director and producer Clint Eastwood. Indeed, Eastwood has said that that American Sniper was meant to criticise war. As he put it, antiwar films are most powerful when they show “what [war] does to the family and the people who have to go back into civilian life like Chris Kyle did”.

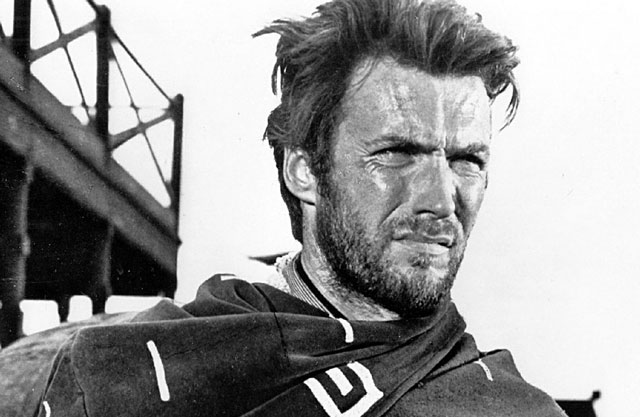

There are two Eastwoods in the popular imagination. On the one hand, there’s the apostle of violence in the Dirty Harry movies and Sergio Leone’s spaghetti westerns; on the other, there’s the man who laments violence in films such as Unforgiven and Gran Torino.

But as American Sniper demonstrates, those two archetypes are not so different. Eastwood does here what he’s done repeatedly in his career: he resolves his hero’s ambivalence, psychic pain and sense of structural powerlessness through masculine honour, sacrifice and vulnerability (often played out on a highly racialised landscape).

Eastwood hit on this formula in one of the first films he directed, The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976). Josey Wales is a poor farmer in the Missouri Territory who, after his home is attacked by Union soldiers, sees no choice but to take up arms and become a Confederate guerrilla. Similarly, in American Sniper, after Chris Kyle watches the World Trade Centre collapse, he feels as though he must go to war. In doing so, both prove to be unusually good — if reluctant — marksmen and killers even as, in both films, the argument for war remains ambivalent.

Their challenge, ultimately, is to work out a way of living peacefully in the absence of war. As Josey says to a Comanche warrior, “Dyin’ ain’t so hard for men like us … it’s living that’s hard.”

The Outlaw Josey Wales contained anti-government sentiments that appealed to Americans on both the left and the right. Coming on the heels of the Vietnam War and Watergate, the film reflected popular disillusionment with both.

When promoting the film, Eastwood often referenced Vietnam and Watergate, alluding to the profound distrust that Americans were starting to feel towards the federal government. But he didn’t simply appear as an opponent of the war and the Nixon administration. Eastwood was openly, angrily anti-government — in a way that not only blamed elected leaders, but also derided impoverished recipients of government assistance. As he told one audience: “Today we live in a welfare-orientated society, and people expect more from Big Daddy Government, more from Big Daddy Charity. That philosophy never got you anywhere. I worked for every crust of bread I ever ate.”

It was the state and people of colour who ultimately violated the Confederate Josey Wales and his family, even though he makes common cause with a Cherokee against imperial expansion of the US state. It is political ambivalence that made The Outlaw Josey Wales popular with a broad public, not unlike American Sniper.

In the beginning of American Sniper, Chris Kyle’s father tells him:

There are three types of people in this world: sheep, wolves and sheepdogs. Some people prefer to think that evil doesn’t exist in the world. If there were ever dark on their doorsteps, they wouldn’t know how to protect themselves. Those are the sheep. Then you have predators who use violence to prey on the weak. They’re wolves. Then there are those who are blessed with the gift of aggression with an overpowering need to protect the flock. These men are the rare breed who live to confront the wolf. They are the sheep dog.

In Eastwood’s rendering of Chris Kyle, Kyle’s need to be a killer of almost superhuman proportions makes him not sociopathic, but rather the sheepdog: someone who operates in a state of constant, anxious alertness against inevitable attack. With this characterisation, Chris Kyle’s violence is justified in advance. Perched up on a rooftop, his rifle cocked, he offers protection from the chaotic aggression of people of colour (just as the real-life Kyle told stories about picking off looters from the roof of the Superdome in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina).

In Clint Eastwood’s Sudden Impact (1983), Dirty Harry Callahan, a white police officer pointing his gun at the head of a black criminal who is holding a white woman hostage at knifepoint. Referring to this scene, political theorist George Shulman has argued that this demonic love triangle between women, blacks and the state fueled the rage of white men who opposed welfare, affirmative action and the ERA in Reagan-era America.

From Sudden Impact, to American Sniper, to the recent cases of police who have killed unarmed African Americans, we can see this logic of white fear and vulnerability at play. Think of Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson, who shot an unarmed Michael Brown 12 times.

“The only way I can describe it,” Wilson testified, “[is] it looks like a demon… It looked like he was almost bulking up to run through the shots, like it was making him mad that I’m shooting at him.”

Ultimately, American Sniper dispenses with conventional political ideology to portray the raw, emotional core of white vulnerability — and its connection to bloodshed in the face of triple insecurities of race, gender and empire in an unstable political era.

But unlike Dirty Harry or Josey Wales, Chris Kyle evinces a woundedness — and, ultimately, a kind of powerlessness — that does not re-establish white male superiority.

After all, Kyle dies — and at the hands of another veteran, no less.

The long, final scene of the film presents actual footage from Chris Kyle’s funeral procession along Texas Interstate 35. Showing thousands of mourners on overpasses (accompanied by a beautiful, melancholy trumpet piece), it asks us to bear witness to the death of a hero. We are not asked to question or challenge the war that made him a killer, or that made him the victim of another American veteran who suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder. Rather we mourn the sheepdog, the emotionally wounded martyr.

In his Studies in Classic American Literature, DH Lawrence wrote: “The essential American soul is hard, isolate, stoic, and a killer. It has never yet melted.” James Baldwin, offering deeper insight on the vulnerable core of this soul, held that that the monstrous violence visited by white Americans on the world is due to their having opted for safety over life.

American Sniper’s Chris Kyle — the sheepdog, the last line of defence — serves as an exclamation point to Baldwin’s keen insight.![]()

- Joseph Lowndes is associate professor of political science at the University of Oregon

- This article was originally published on The Conversation