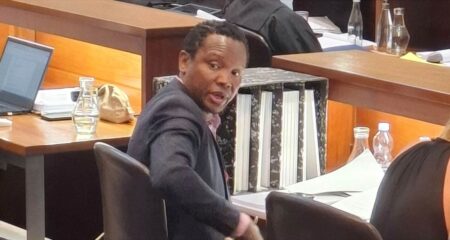

Nkosana Makate, the man who is suing telecommunications giant Vodacom for the “please call me” invention is upbeat that his constitutional court bid might bear fruit.

After the high court in Johannesburg last year dismissed Makate’s case, he is now looking at the highest court in South Africa to appeal the decision.

In March, Makate’s case suffered another blow when the supreme court of appeal rejected his application for leave to appeal on the basis that his prospects for success were limited.

In his affidavit, Makate claims that the high court denied him the right of access to court under section 34 of the constitution and the right to property in section 25.

“In conducting itself as it did, the high court undermined my right … to have my dispute with Vodacom ‘decided in a fair public hearing before a court’. It reached a conclusion that precluded me from having the relevant legal and factual issues decided in my favour — even though they had been raised on the pleadings,” he says.

On section 25, Makate says he was “deprived” of the invention and the right to claim money for it “even while Vodacom continues to benefit to the tune of many billions of rand”.

Makate also suggests that the court needs to lay down a principle on the fact that the parties are in an unequal bargaining position.

In 2000, Makate was a trainee accountant for Vodacom when he claims to have invented “please call me”, a free service which enables a user without airtime to send a text to be called back. Makate says the idea was borne out of his long-distance relationship with his then girlfriend (now wife) who was unable to call him as she could not afford to buy airtime.

When the idea hit, Makate spoke to Vodacom’s director on the board and head of product development at the time, Philip Geissler, as “he was the obvious person to speak to given his position”.

“He was the man who approved new products within Vodacom and oversaw and managed their roll-out,” he says.

He says Geissler agreed to pay him a share of the revenues Vodacom would generate from the innovation if it was technically and financially viable.

Makate says the “lucrative” innovation generated billions for Vodacom over the years. He estimates that the invention, since its inception in 2001, has generated about R70bn for Vodacom and he wants a 15% cut of the profit share.

“Vodacom has consistently breached its agreement with me by failing to pay me any share of its revenues or any ongoing remuneration for its continued use of the product. Every month passes as Vodacom earns more revenue from my invention, a fresh breach occurs and a fresh debt comes into existence.”

The high court case, presided over by judge Phillip Coppin, concluded that Makate had successfully proved the remuneration agreement between him and Geissler. However, Coppin dismissed Makate’s claim on the basis that he did not prove that Geissler did have “ostensible authority” to bind Vodacom in an agreement of compensation.

Also, the court found that Makate’s claim against Vodacom had expired (a term known in legal circles as prescription), as he did not file the claim within three years of Vodacom going to market with “please call me”. Makate pursued his initial court bid in 2008.

“My claim against Vodacom had prescribed notwithstanding the fact that my claim is an ongoing one and that at best only part of my claim for the initial period could have been hit by prescription,” he says.

Makate further questions the high court’s interpretation of ostensible authority, as he believes it “misunderstood the legal principles” of the term.

He says the court failed to lay down a principle that ostensibly authority must be considered differently in circumstances where “the parties to the alleged agreement have fundamentally [an] unequal bargaining power.”

Vodacom responds

Nkateko Nyoka, chief legal and regulatory officer for Vodacom, says Makate’s leave to appeal should be dismissed mainly on two grounds — misinterpretation of ostensible authority and prescription.

Vodacom says the Makate waited eight years before instituting proceedings against the company, which means his claim has already expired (prescription). It further argues that no official at Vodacom had the actual or ostensible authority to bind Vodacom in a compensation agreement.

Vodacom says it was against the policy and practice of the company to offer employees additional remuneration and enter into revenue shares with employees. Vodacom’s agreements had to be in writing, but “Makate never obtained a written agreement or even a written confirmation of his alleged oral agreement”. It adds that all agreements need to be approved by the legal department — which was not the case with Makate.

“Consequently, with no reliance being placed on actual authority and no pleading of ostensible authority, the contractual claim must necessary fail and Makate on this ground alone has no prospect of success on appeal,” it says.

On the unequal bargaining position argument between Makate and Vodacom, the company labels it as “an attempt to infuse constitutionality into a non-constitutional issue”.

The price of the invention (with no technical solution) would have been worth “a few thousand rand”. “Thus, the claim [for compensation into billions] is ill-founded and grossly inflated,” it says.

The constitutional court could give a ruling on the appeal in May.

- This article is republished from Moneyweb with permission