Facebook tried to get ahead of its latest media firestorm. Instead, it helped create one.

The company knew ahead of time that on Saturday, The New York Times and The Guardian’s Observer would issue bombshell reports that the data firm that helped Donald Trump win the US presidency had accessed and retained information on 50m Facebook users without their permission.

Facebook did two things to protect itself: it sent letters to the media firms laying out its legal case for why this data leak didn’t constitute a “breach”. And then it scooped the reports using their information, with a Friday blog post on why it was suspending the ad firm, Cambridge Analytica, from its site.

Both moves backfired.

On Friday, Facebook said it “received reports” that Cambridge Analytica hadn’t deleted the user data, and that it needed to suspend the firm. The statement gave the impression that Facebook had looked into the matter. In fact, the company’s decisions were stemming from information in the news reports set to publish the next day, and it had not independently verified those reports, according to a person with knowledge of the matter. By trying to look proactive, Facebook ended up adding weight to the news.

On Saturday, any goodwill the company earned by talking about the problem first was quickly undone when reporters revealed Facebook’s behind-the-scenes legal manoeuvring. “Yesterday Facebook threatened to sue us. Today we publish this,” Carole Cadwalladr, the Observer reporter, wrote as she linked her story to Twitter, in a post shared almost 15 000 times. The Guardian said it had nothing to add to her statement. The Times confirmed that it, too, received a letter, but said it didn’t consider the correspondence a legal threat.

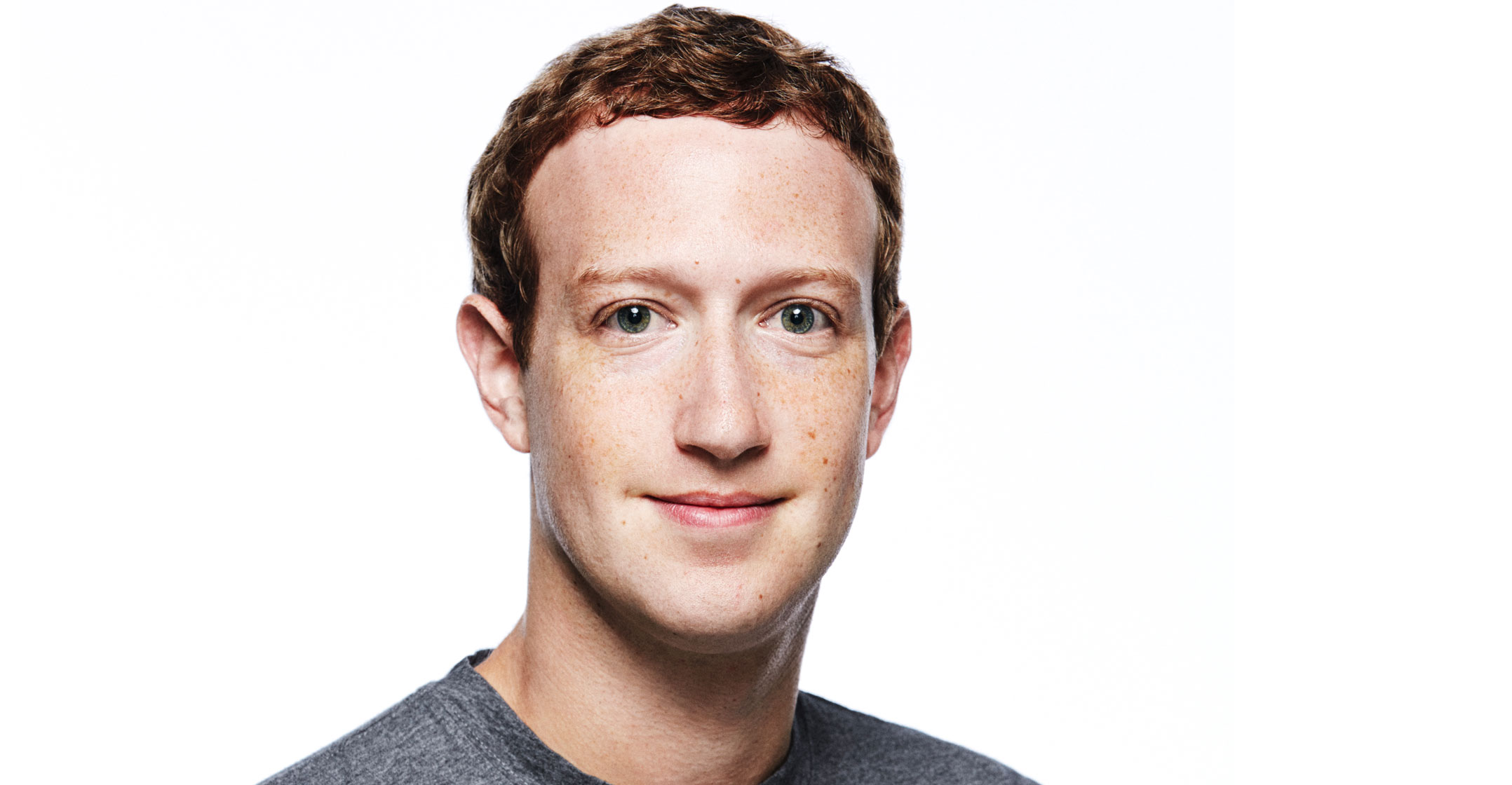

Front-running the stories along with the letters to newsrooms are but two of several ways Facebook failed to contain fallout from the Cambridge Analytica revelations. Silence on the part of CEO Mark Zuckerberg and chief operating officer Sheryl Sandberg didn’t help. Nor did a report late Monday in The New York Times that chief security officer Alex Stamos is leaving after clashing with other executives, including Sandberg, over how Facebook handled Russian disinformation campaigns. Facebook said Stamos is still at the company, but didn’t outright deny that he plans to leave.

Reaction

“Most of its executives haven’t done a real interview in ages, let alone answer deep questions,” Zeynep Tufecki, an associate professor at the University of North Carolina who specialises in social networks and democracy, wrote in a post on Twitter.

In a sign of investor dismay, Facebook shares tumbled 6.8% on Monday, the biggest decline since March 2014. As the stock fell and criticism from lawmakers poured in from the US and Britain, the company worked to make it clear that it didn’t actually have enough information, on its own, to react to Saturday’s news reports in a stronger way.

Facebook put out another blog post, saying that Cambridge Analytica and the researcher who provided them the data, Aleksandr Kogan, had agreed to a digital forensics audit to prove they deleted it. Facebook said the one person who didn’t agree to the audit was Christopher Wylie, the former Cambridge Analytica contractor who spoke to the newspapers about the data leak. With the post, Facebook aimed to stir more scepticism around Wylie’s information, according to a person familiar with the matter.

That didn’t resolve things quickly either. The auditors were already on site at Cambridge Analytica’s London office Monday when they had to pause their work. The UK Information Commissioner’s Office is pursuing a warrant to conduct its own on-site investigation.

The Cambridge Analytica saga is the latest in a series of bungled Facebook responses, often reactionary and sometimes unintentionally stirring public outrage instead of resolving concerns. The company’s interaction with the public tends to start with a carefully crafted blog post, and then evolve into a much more improvised Twitter-based conversation with lower-level executives who defend the social network and explain its decisions. It doesn’t always go well.

Earlier this year, when the US government indicted 13 Russians who used Facebook to manipulate voters, a Facebook advertising executive took to Twitter to clarify that overall, the Russian ads were primarily used to divide Americans, not influence the election. His comments went viral after Trump used them to back up attacks on the “fake news media”.

In 2017, Facebook made its disclosures on Russia’s activities in a slow drip, each time illustrating a bigger problem. An April white paper on “information operations”, for example, didn’t name the country. The company that October said 10m users saw Russia’s ads. Later that month, Facebook said 126m people saw Russia’s posts in general. The company upped the number to 150m during congressional interrogation, when a senator asked if Facebook could include Instagram, the photo-sharing app it owns, in the count.

Stamos, who has favoured more forthright disclosure, was frequently outvoted, according to The New York Times. He’s planning to leave the company in August, the newspaper reported. On Twitter, he later said he’s still fully engaged with his work at Facebook, without answering questions about his plans. But that would make him the most high-profile exit since Facebook’s election-related troubles began.

Meanwhile, higher-ranking executives remain quiet. Zuckerberg and Sandberg, who in past years would post frequently about the issues of the day, have shied away from reacting to the most controversial news. Lawmakers have now called out Zuckerberg by name in both the US and the UK.

Zuckerberg and Sandberg plan to remain quiet on the Cambridge Analytica situation until the company completes its internal review of what happened, according to a person familiar with the matter. Until they do, questions about Facebook’s ability to cope with the Cambridge Analytica crisis will undoubtedly persist. — Reported by Sarah Frier, (c) 2018 Bloomberg LP